Over the last six years, the Gothenburg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (GIBCA) has positioned itself as a forum for re-examining Sweden’s colonial past and speculating on utopian futures. So when Christina Lehnert, curator of the 13th edition, promised a pivot to the present – no detours, no evasions – it was a welcome change.

Yet, I probably wasn’t the only one to cringe at the curatorial statement’s lazy phrases about “care that extends beyond personal concerns” to “investigate how art can facilitate dialogue.” Indeed, if GIBCA promotes artists who avoid personal expression out of fear of being divisive, hasn’t it already yielded to the very “political pressure” it claims to resist by striving for “artistic freedom”? What kind of freedom are we fighting for, anyway? Freedom from artists who express themselves personally?

Based on this shaky premise, some twenty artists were invited to showcase their work at the Gothenburg Museum of Art, the city library, and Röda Sten Konsthall. Gothenburg Konsthall is temporarily closed, so part of the biennial has relocated to Skövde Art Museum, 150 kilometres to the north. As I travelled between these venues, it became clear that GIBCA 13 was as intellectually scattered as it was geographically dispersed.

I started my tour at the Museum of Art, where works by Palestinian artist Basma al-Sharif, Black Archives Sweden, and the Swedish artist Moki Cherry (1943–2009) were installed in three galleries hosting late nineteenth and early twentieth century art. Here, faced with the idyllic scenes of Nordic turn-of-the-century painting, the urgent present seemed to drift away. Listening to old recordings of activists Angela Davis and Kwame Ture (born Stokely Carmichael, 1941–1998), courtesy of Black Archives Sweden, or viewing yet another presentation of Cherry’s iconic psychedelic appliqués in a Swedish museum did little to alter my mindset. Why not honour the legacies of these radical figures by inviting contemporary artists with equally compelling things to say today?

In the next room, al-Sharif’s film Old Masters (2025), surrounded by the captivating gloom of National Romantic mood painting, had a stronger impact. Set to Beethoven’s hauntingly melancholic Moonlight Sonata (1801), the camera follows a Western-looking man walking through a museum – first forward, then backward. Then we see an elderly Palestinian woman in a garden, and hear the man respond to a question about how, in the future, he would tell someone too young to remember about the genocide in Gaza.

Surprisingly, the man says that he wouldn’t want to tell the story at all. I understand him to mean that, as a European, he wouldn’t want to be the one to narrate it since Western memory culture has done Palestinians and other subjugated peoples little to no good. The strength of al-Sharif’s film lies in how it points to the violence taking place off-screen, in a world where the museum and its ‘masterpieces’ will remain long after Gaza has been obliterated. Then the West will ‘remember’, and by then it will be too late.

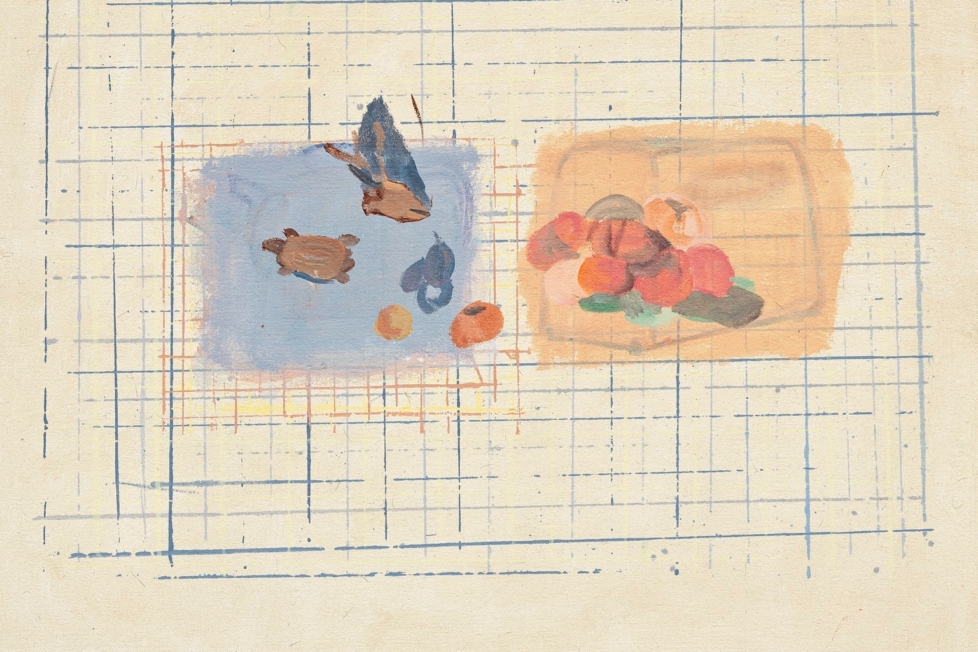

I left the museum disheartened, hoping for a more compelling curatorial statement at GIBCA’s main venue Röda Sten. Here, works by some ten artists have been installed across four floors at the disused industrial building. Upon entering the vast second-floor hall, a series of paintings by Rosalind Nashashibi were visible through an ominous fence. Scrawled across the canvases, the acronym “UNRWA” recalled how the boycott of the Palestinian aid organisation contributed to mass starvation in Gaza. A painting referencing Antoine Watteau’s L’Indifferent (1717) exposes Western hypocrisy in the face of Israeli war crimes. The fact that Sweden was one of the few countries to heed the master’s call to cut UNRWA funding in 2024 made the inclusion even more poignant.

Yet, Nashashibi’s contribution felt like an echo of a more powerful exhibition that never was. Across the other floors, works like Puppies Puppies’ Executive Order 9066 (Soul Consoling Tower) (2019), on American internment camps in the 1940s, Lydia Ourahmane’s Haraga – The Burning (2019), on Mediterranean migration, or Raven Chacon’s Silent Choir (2017), on Indigenous protests against US pipelines, seemed to evoke Achille Mbembe’s concept of necropolitics, referring to states’ power over life and death. Yet, focusing on the victims of oppression, rather than those responsible for – or profiting from – the system, the show offers little in the way of accountability. Usually, Röda Sten is the beating heart of the biennial, but this instalment appeared weak and disjointed.

By contrast, Skövde Art Museum offered a surprisingly cohesive “show-within-the-show” focusing on art as an agent of social change. The museum is located in the town’s Cultural Centre built in 1964 – a pinnacle of postwar, Social Democratic cultural policy expressed in a mammoth brick building housing a library, a theatre, a cinema, and more. The building also features permanent works by Swedish artists Siri Derkert (1888–1973) and Vera Nilsson (1888–1979), whose feminist activism inspired the selection.

Here, political posters by Pakistani artist Lala Rukh (1948–2017) are installed alongside Olivia Plender’s work on the history of women’s struggles, and an installation by Patricia L. Boyd that uses disjointed architectural elements and cardboard boxes to visualise the mutability that politics speaks of. Yet, when the soundtrack of Plender’s video – with women chanting “shame on you!” – echoed through the space, it felt oddly decontextualised. Holding up a mirror to the viewer can be effective, but here I became weary of GIBCA 13’s consensus-driven politics of shame.

Today, many see polarisation as a problem, and long for a time when we could still “think beyond Us and Them,” as Lehnert puts it in her curatorial statement. But rather than lament the decline of culture, why not address it, as it were, head-on? After all, the problem isn’t disagreement, but disconnection: people retreating into ideological echo chambers and bickering over minutiae instead of trying to comprehend the bigger picture. Indeed, visualising larger pictures is exactly what biennials are good for.

Yet, in contrast to recent instalments of GIBCA, which sought to map out meaningful relationships between artworks and the world they reflect, the 13th edition settles for flat-packaged themes left for visitors themselves to assemble, while ultimately lacking the structural integrity to confront the present it claims to engage. How do we move beyond moral policing and the desire to educate and condemn? GIBCA 13 has no answer to that.