On the first weekend of September, Fred Moten, the US-American thinker, essayist, and poet, known for his prolific genre-expansive writing and interdisciplinary activities, visited Oslo for the first time. A professor in Performance Studies at New York University’s Tisch School of Arts, Moten has contributed significantly to discourses about blackness and the African diaspora.

In addition to a number of poetry collections, Moten has in the past two decades authored and co-authored several theory books. Among the most discussed are In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (2003), The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (2013), written in collaboration with the scholar and activist Stefano Harney, and the three books of essays comprising the project consent not to be a single being: Black and Blur (2017), Stolen Life (2018) and The Universal Machine (2018). In 2021, Moten and Harney further reflected on the topics they approached in The Undercommons in their second title together, All Incomplete.

Invited by the research centre FORART to hold its yearly open lecture, which took place at Litteraturhuset, Moten shared ideas about observance, observation, and how Black communities grieve our losses. A second event of the tour was held at the Astrup Fearnley Museum, where he read poems from his recent book, perennial fashion presence falling, a title that bears a clear reference to Theodor W. Adorno’s infamous critique of jazz.

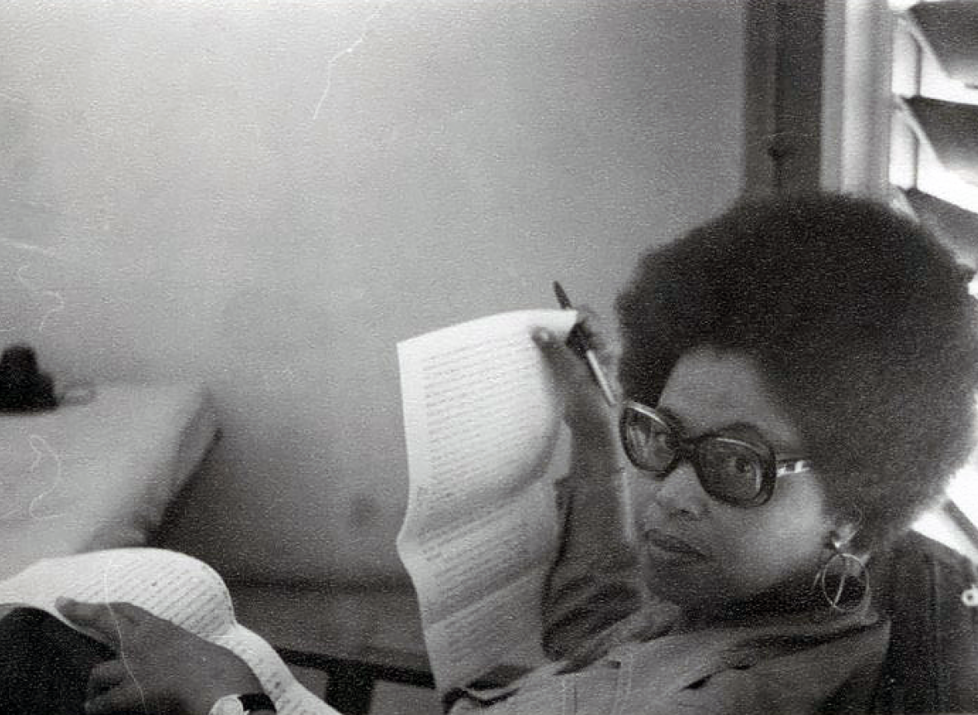

Following the poetry reading, Fred Moten generously opened space in his schedule to answer some of my questions about, among other themes, subjectivity, representation, and collaborative writing processes. Our conversation turned out to be a visit to some of the crossroads in Afro-diasporic experiences, spaces Moten has chosen to inhabit time and time again, and from where he creates knowledge in collectivity.

One of several things you point to in your work is the object-subject relation, that includes ideas like the resistance of the object and the connection you see between subjectivity and subjection. Could you elaborate on that?

The first thing I would say is that we all have lived through the experience of being objectified. And it’s a complex experience. It’s full of all of these interesting possibilities. But in general, the experience of being an object is an experience of oppression. And so, historically, the discourse that seeks to align itself with the fight against oppression has assumed that the proper way to do that is to claim subjecthood, to claim what people sometimes refer to as personhood or agency. But I think that the tradition of black critical thought* – and especially the most powerful and animating strain of black radical thought, which has always, I think, been black feminist thought – is much more critical of this notion of achieving or finding or claiming subjectivity.

That strain of thinking is multi-generic. It manifests itself in visual art, in music, in literature, in history. As I was coming into developing as a student and a scholar, my first exposure to that thinking was my mother and her friends who raised me, the people around whom I grew up. But when I went to school, went to college, and in graduate school, the people whose work extended those lessons that I learned at home were these great critics like Hortense Spillers, Sylvia Wynter, Adrian Piper, and then eventually many people from my own generation like Harryette Mullen, Saidiya Hartman, Sharon Holland, and Farah Jasmine Griffin, and younger scholars such as Alissa Trotz and Katherine McKittrick, and many, many others going back to Mary Prince and Harriet Jacobs. I feel like my work, what I’m doing, is part of a longer, richer, deeper project that stems from those folks.

This totally justifiable reactive formation to claim subjectivity is one that we need to not only think critically of, but that we need to try to abolish. It’s a difficult task because it implies a fundamental reorientation. Everything that we think and how we think now has to be challenged and transformed. That’s always a painful thing, but the most painful thing is that even the ways that we have come to both know and to memorialise our losses have to be questioned. It’s totally unfair, right? We shouldn’t have to do that. It shouldn’t be our responsibility, but it is. So that’s pretty much what I’m trying to do: my part in that work.

In Norway, the Black and Brown communities, and also the Nordic Indigenous communities have been claiming representation in all those beautiful institutions that are also built with our labour, our tax money. That is why I understand what the pain is about. We have been talking about representation for many, many years. Coming from Brazil, I see how the thought about blackness and Black Studies has developed in the African diaspora in the Americas. We don’t have Black Studies in Norway, and the idea of establishing such a learning environment here may seem really far-fetched. It is easy to assume that the language and the actions in the Americas are very much ahead of what we have achieved here, where things evolve slowly. What you bring sounds post-humanist, while in most contexts we are still claiming humanity. There is a sort of tension in the fact that the community demands representation and your thought is going in a different direction. How do you position yourself in these terms?

I generally am wary of the prefix “post.” I don’t know if anything can ever adequately claim or embody that sense of being “after.” But the one thing that I probably feel the best about, is post-humanism. I do think that is a fundamental part of the work. It has got two elements to it; in the sense that we have to confront two things.

One is, again, the way in which we have come to understand our oppression is that it takes the form of a denial of our humanity. However, human beings are the agents of that denial, which ought to give us pause about claiming the status of the human. Because if humans can be slave traders, if humans can destroy the environment, if humans can do all the bad things that humans do, then maybe we ought not jump so quickly, right? Humans do some interesting things too, no doubt, but it is very unclear if the good stuff outweighs the bad. And what it has produced is a situation that we now live in, in which humans are not only destroying as many other species as they possibly can, but human beings are also very quickly destroying the capacity of our own species to survive.

Then we also have to confront the fact that the very idea of species is itself a human invention. From our framework, it appears to have some intellectual justification, but of course, in every other modality of thought, that would not be a sufficient way to actually assess its value. In other words, if something is only true from one perspective, we generally say, well, that’s kind of suspect. I don’t think that lions and tigers have an idea of species. It’s not to say that lions and tigers are all good.

We cannot actually go to nature looking for the ethics that humankind created and developed.

There’s a differential. You know, there is a common set of differences that we might be said to share, but it’s unclear that that common set of differences justifies the thought that we are therefore separate from other entities on Earth. Another extraordinary black feminist thinker from Brazil, Denise Ferreira da Silva, would say that we ought to be able to have a notion of difference that doesn’t devolve into separability.

So, I believe that this, again, justifiable reactive gesture to claim humanness is problematic because of the history of the bad things that humans have done. One of the most important things that Saidiya Hartman’s work shows is that it’s probably the case that, in most instances, the specific degradations that were visited upon black people throughout the Americas – from Canada to Argentina – were not imposed because the masters didn’t think that we were human, but because they knew that we were. They did things to black people that they wouldn’t do to dogs and horses. And they wanted things, right? They desired things from black people that they did not desire from dogs and cats.

On both of these scores, the reactive sort of gesture to claim or to reclaim the human is one that at least should require deep, deep investigation. That doesn’t mean that I feel like I’m always in some pitched battle with people who imagine that they can claim the human or that they are interested in a revision of the human. There are very smart people whose work has been important to me, who, in our tradition, constantly make this claim: Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Paul Gilroy, Sylvia Wynter. I’m not saying this to dismiss what they say, but I feel like it’s an actual extension of the investigation that they have also been part of. It is a pretty sharp difference, and it has to be worked through, but we still share this tradition. That would be the reason why there is a moment in which I want to say, “yes, it is a post-humanist thing.” But to the extent that I would maintain this affiliation, I hope, with Wynter or even with Gilroy, I would be wary of the term “post” because I don’t want to be in some situation or in some vein of thought that’s after Wynter. I want to be with Wynter, not after Wynter.

Speaking about prefixes, you have used “para-” [beside, alongside of, beyond, aside from] quite much. Reading and listening to some of your work, one gets the impression that you are repeatedly choosing to be in philosophical, philological and artistic crossroads. In the Afro-Brazilian rituals of the Candomblé, one of the most powerful energies is connected to the crossroads – both literally and metaphorically – I believe those are wonderful places to find oneself at, but sometimes the most difficult too. You have in different contexts spoken about the paraliterary and the paraontological. Then you tell that anecdote about your French friend who with her accent makes the words ontological and anthological sound almost alike, which again creates another path for reflections. Could you develop on these uses of the prefix “para-” as there are many ways that one can go from there?

Well, on a more abstract level, there is just this feeling of the necessity for abiding with contradictions, paradoxes, and that these are things which are not to be resolved. But as my teacher, mentor, and model Cedric Robinson would say, these contradictions and paradoxes are to be heightened and deepened. Some of that is just because growing up in the house I did – with the people that I was with, the art and the thinking that they were involved in, that they were interested in – we were constantly confronted with these paradoxes, and they were understood to be sources of pleasure and energy. I think that prepared me to school, to learn about other traditions.

One of the poets that I love the most is this English Renaissance poet named John Donne, who is extraordinarily interested in paradox. His poetics is just replete with all these paradoxes. It became a kind of critical paradigm that I wanted, that I was always drawn to. Then I had the fortune of finding that again in a more formally enacted and analysed way, in the work of a couple of great, great, great black thinkers who I was drawn to years ago. The first is Samuel R. Delany, a speculative fiction writer who was the person who introduced me to the term paraliterary as a way of describing science fiction, and as a way of valuing certain kinds of literary modes which were deviant, which deviated from norms of so-called realism. Those in fact turned out to be norms that are very much tied to that subject-object opposition, to the ways of thinking, of being in the world, knowing the world, and eventually of owning the world; norms that are implied in that distinction between subject and object. I have never used the term in any way other than as an attempt at least to echo something that he had been thinking, his notion of the paraliterary and his elaboration of that term. Of course, that means echoing whoever it is that he got it from.

The paraontological [referring to the idea of disrupting ontology as a normative philosophical category] is a little different because I always have associated that term with another great black scholar and thinker, whom I was for a while very close to and still feel close to in the sense that I think we are trying to work along similar lines and out of a similar trajectory. His name is Nahum Chandler. The first time I heard that term was when he said it. I think it was so suggestive to me that I ended up sort of taking off and running with it in a way that probably deviated from some of the ways that he might use it and that he would feel comfortable with. Nahum is a person who is so fastidious in his scholarship that I always thought: “He is not the kind of person who revises things. He just rewrites them.” He just starts all over, and he would send me texts, and I would have these various iterations of his work which sometimes mentioned the term paraontology, and a lot of times did not, but which I thought were very much inflected by his notion of paraontology. When I did use that term, I was always trying to make sure that everyone was clear that the term came from him, even if I was probably deviating from his notion of the term.

I later found out from another friend, another great black scholar and thinker named Ronald Judy, that the term paraontology was originally used by this important but very problematic German thinker named Oscar Becker, who was a student of Edmund Husserl’s and a fellow disciple of Husserl with Martin Heidegger. His notion of paraontology is interesting, suggestive, and rich but, like in Heidegger or maybe even more intensely than in Heidegger, it folds into Becker’s really ugly, problematic politics, and his Nazism.

Can paraontology be connected to the idea of the Übermensch?

Well, that’s an interesting question. There is probably a way in which I would have ultimately said: “Yes, that is true.” But to say that is to say a complicated thing. The notion of the Übermensch is a philosophical term, and we know it primarily as a Nietzschean term, which was adopted by Nazism, and also very much distorted by Nazism. However, there is a compatibility, yes. Which is not to say that there is a direct line between the notions of the Übermensch and paraontology because I do not know that that is the case.

There is nothing about the term paraontology that made it impossible for Becker to be a Nazi, and in this respect there was nothing about the phrase “all men are created equal” that kept Thomas Jefferson from being a slave owner. But another, and more disturbingly precise, way to put it is that perhaps there is something about those terms that made it possible for Becker and Jefferson to be the monsters that they were and are. I think that has to do with very deep questions concerning two things. One is the limits of theoretical activity, which is generally understood in itself to be an essential hallmark of the self-determining man. First of all, I don’t believe that there is some ultimate, final, best theoretical proposition to be made, or some unique and proper conceptual scheme from which it could be made. And even if there were, it still would not absolve us from the work of dealing with the problems and chances of social and aesthetic practice. The work of dealing with practical problems will almost always mean deviating from and violating the theoretical assertion. But it also means that we have to deal with the history of our own inheritance as thinkers.

There is a scholar in the United States named Axelle Karera who has written about this term, paraontology. She means to expose the terrible origins of this term and to take certain thinkers to task in their use of it. She wants to suggest that it produces a condition of problematic indebtedness to the thinker who originates those terms. My sense of it is that, no, it is really not a matter of indebtedness. It is more problematic than that. It is not even a matter of inheritance. It is a matter of kinship. The history of thought produces strange kinship relations that often we don’t want to acknowledge because we don’t want to be seen as being related to Heidegger because he was so much of a… bastard. I don’t want to be related to Thomas Jefferson, but every instance in which I begin to engage in the discourse of freedom and equality is a moment in which I show that kinship. Now, we then have to say something about that, and maybe we also have to do something about that, but we certainly cannot deny it.

Again, this is very much tied to that whole problem of claiming subjectivity. We have to recognize that our struggle for liberation is given in the language of liberalism. That is not just true for Barack Obama. It is true for Frantz Fanon. It is totally clear. It is undeniable. We might not want that to be true, but it is. We might not want there to be a kinship between Frantz Fanon and Daniel Patrick Moynihan [a former US politician, 1927–2003], it is unseemly, that it is. We can love Fanon and hate Moynihan, but there is a kinship there, and it behooves us to pay attention to that. It goes beyond the intentions of an individual thinker. That is why it is not really a matter of indebtedness to a thinker. It is a matter of kinship within the practice of thinking.

There is no cleansing that can be done. Instead, these are paradoxes and contradictions that we have to recognize that we inhabit and then figure out a practical, ethical approach to that inhabitation. That will allow us to actually practice our difference from Heidegger rather than assert it as if it were an identity. We have to work that and play that as a practice.

This makes me think that some Afro-diaspora scholars are still working with the idea of decoloniality, but it may at some point in the future be necessary to reject it. For example, I have not heard you use this term, and I see other thinkers, especially Black feminists, speaking about liberation in other terms. This may go into what you say about things being related or inseparable, a word you used in your lecture about observance and observation. Decoloniality and coloniality are inseparable.

Only under very specific circumstances would I use the term decolonial, and it really is only to refer to a set of practices which I think now can properly be called that way. I also use it to refer to a sort of attitude that is present, at least in my understanding, in scholarly circles. Primarily, I think it shows up as a moral claim that can easily devolve into a kind of moralism. It accompanies a kind of scrutiny that is imposed on people, so you can see whether or not they are properly decolonial, you know? It is puritanical in that way. Even the prefix “de-” implies the possibility of an absolute cleansing. I am not saying that every decolonial thinker believes that there can be some absolute eradication of coloniality, but it produces that general moralistic atmosphere. So, I prefer the term anti-colonial, which to me implies a more or less interminable commitment to fight colonialism. But I am older. The thinkers that I was brought up with, raised to admire, and want to affiliate with, they were anti-colonial thinkers. They were involved in anti-colonial practices. What we know now about the history of so-called postcoloniality is that it did not on any level create a situation in which anti-coloniality was no longer needed. Anti-coloniality is needed now, more than ever before.

At the same time, this is a nod to some of your contemporary thinkers, such as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

Oh, yes! Absolutely. She is one of the primary teachers of this. But Fanon was already approaching this topic. He already understood this in his work. There is a great scholar named Adom Getachew. She wrote a really interesting book called Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination [2019]. She also wrote this amazing review of a book by Orlando Patterson, The Confounding Island: Jamaica and the Postcolonial Predicament [2020]. I have been thinking a lot about postcoloniality, together with Stefano Harney and other people, under the influence of Getachew’s work. And not just her work, but also that of the Guyanese feminist organizer and thinker named Andaiye whose work is amazing.

Here is the question that most of us in the world now have to confront, and I think it is already implicit in Sylvia Wynter’s work, too, which is: How is it that postcolonial structures, postcolonial politics, which have emerged by way of so called decolonial means, find themselves involved in the administration of coloniality? That is a problem. It is a problem in Africa, in India, and there is a very specific way in which I think it has been a problem for the last fifty years in the United States. My sense of it is that it is becoming more and more of a problem in Brazil too. It manifests itself precisely as the dangers of being represented within old structures which needed to be not infused with black presence, but which needed to be destroyed and continually eradicated. I don’t know that there will ever be a moment in which they will be completely destroyed. There is a vigilance that is required.

Radical work in the original sense of the word.

Yes. We think of colonial institutions as, for instance, banks – the East India Company or various economic and governmental structures that are left in place. But what if it turns out that the very figure of the subject is itself a colonial institution? What if it turns out that representation or inclusion are also colonial institutions that converge with the figure of the settler? I am asking that question because I am almost sure that it is the case. If we put that forward as a hypothesis that is to be tested, and if it turns out that I am wrong, that is okay. But at least it is something that I think needs to be thought about.

It is the kind of thing you want to be wrong about.

Look, I would be happy to be wrong, but I don’t think I am. One way to think about it is that in the US, as a function of deep, deep, deep and absolutely necessary and an absolutely legitimate struggle, we entered into a phase, since the mid-1950s, of increasing inclusion and representation. It feels very much like that phase is coming to a close, that that window is closing or at least transforming in pretty radical and problematic ways. If that means we are ahead of the way of thinking in Norway, like you suggested, we are ahead in a way that a canary is ahead of the miners.

There is an experiment, and let’s call it what it is: An experiment in neoliberal governance that was initiated in the United States, and it was initiated in many ways as a regulative response to radical insurgency. There is a tremendous force that is being exerted on already existing structures of governance, and power figured out that it needed a two-pronged way of responding. One was brutal and militaristic, in the form of increased policing and all of that. The other was inclusion and co-optation. Inclusion and co-optation was the form that it took for the Democratic Party. Policing and brutality was the form that it generally took for the Republicans. But it is important to think of this as a two-pronged attack.

This is what I was trying to say in my lecture. It is a two-pronged attack on the force of black radical insurgency, which was a reconstructive force, but also a deconstructive force. It was not about being included in the already existing thing. It was supposed to be a powerful transformative force. These fruits that emerge of inclusion, and I am one of them in the sense that the accident of being born at this historical moment meant that I could reap a lot of the so-called benefits and so-called privileges of being included in situations where heretofore black people were radically excluded… But, again, like the canary in the mine. I could say: “Look, maybe you can breathe down there, but it’s not really fresh air and it’s unclear if we can get where we’re trying to go going that way.”

In your lecture, you spoke about a window in time between desegregation and the end of the affirmative action for racialised minorities in the US. You called that period of time a window of opportunity but also a window of betrayal. There are many examples, but the first name that came to my mind was Clarence Thomas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, a Black man who benefited from the affirmative action in his youth, but now voted to end it. How did the US arrive here after having a Black president?

Obama’s election in 2008 was, unfortunately, nothing more than an extension of the already existing paradigm. And it was a moment in which black folks in the United States and all over the world celebrated it as a moment of instantiation of the promise of representation. But it was an extension of the historic colonial disaster and catastrophe that has befallen Black people for five hundred years. It was an extension and an enforcement of that. However, people don’t want to say that; people don’t want to deal with that, even now. But we’ve got to have something that exceeds the desire to be represented. At the same time, of course, how could the desire to be represented be anything other than utterly justifiable and legitimate? See, that’s the thing. It is totally justifiable.

From the perspective of the people who have guarded against representation, there is no critique of it that they could possibly have to offer. The critique of the desire for representation has to be a critique that black people generate. Not that Bolsonaro generates, not that some right-wing fucker in the US generates. It is a critique that we have to generate for ourselves, which seems to be a totally unfair burden. But nevertheless, it is our job to formulate, just like what Spivak says, it is the function of education, which she says is the non-coercive rearrangement of desire. We have to learn how to desire something more than that. And it is terrible, right? How do you learn how to desire something more than being a human, something more than being a person, something other than being a fully-fledged individual subject, something other than being represented? How does an artist come to desire something other than being at this museum? [Points to the surroundings.] Or how does a black scholar desire something other, or more, than being a professor at Harvard, or Yale, or NYU? Like I said, I don’t absolve myself from these questions. They are the questions of my life. I have no pure position from which to articulate these questions. That is the whole point. I am implicated in every one of these questions.

The betrayal, that word specifically, comes from this rich, beautiful encounter between the work of Andaiye and [Barbadian author] George Lamming, from her criticism, her beautiful, literary, critical attention to Lamming’s In the Castle of my Skin (1953). She articulates this notion of betrayal, and she asks: “How have we arrived at a position in Guyana, in the postcolonial Caribbean, in which those whom we have nurtured and sacrificed into power now give aid and comfort to our enemies?” She uses the term betrayal to name that. When I first read it, I was like… well, it is a question that gets deeper every time you think about it, right? Because it is not just asking: “How did these people come to betray us?” When she says “nurtured and sacrificed into power,” that’s got a double edge to it. On the one hand, it could mean we have nurtured them and we have sacrificed for them so that they could come into power. But it also means we have nurtured and sacrificed them to power. We have sent them away to become these people, and now we have to confront the fact that they did, in fact, become these people. And those people are the ones who oppress us.

The betrayal was given all the time, right?

Yeah. And what I believe she does in asking the question in that rich and complex way is it exceeds the sort of narrow calculus of individual morality. It is not a question that lends itself to some puritanical moral superiority. It is like: “Look, this is the boat that we are in. This is where we are.” This is not something that you use in order to denounce somebody that you don’t like because they got something that you don’t think they should have or that you think you should have or whatever. No, this is a general problem that has befallen us. This is an extension of coloniality that we have to work through together.

I would like to talk about some of your books. It is now twenty years since the publication of In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. It is still very pulsating and up-to-date. I would also like to hear more about your journey into collaborative writing projects with Stefano Harney, for instance.

Well, it is funny because I don’t look at In the Break very much. When I do, I just see stuff that I wouldn’t say that way now. I don’t think it is wrong or disavowed. I just feel like I could approach a greater level of precision now. More than anything, In the Break was my PhD dissertation. It started off as definitely something I was interested in and deeply committed to. It is revised in some way, but there is stuff in In the Break, and then there is an essay called ‘Knowledge of Freedom’ that is in this book called Stolen Life; that was in my dissertation, or at least the early versions of it. In other words, it was part of this very individualised professional development. It was about getting a job and keeping a job. But Stefano and I went to college together, so we have known each other for forty years. We worked on a literary magazine together in college. We were friends for years and years – twenty years before we ever wrote anything together, which was a result of us casually being both in New York at the same time. So, I knew Stefano before, let’s say, I became a professional.

I also collaborate a lot with my partner, Laura Harris. We have been together for almost forty years now, too. Everything I do, everything that I have done in my so-called adult life, like I said, it started with my mom and the people I grew up around, and it was enriched and deepened, but also very simply required and allowed by my friendship with Laura and with Stefano, and with a few mentors and a few other true friends. Everything has been part of this sort of collaborative project.

I was sent into this realm of individuation by my mom with this very contradictory instruction of “go, make a living, prosper as an individual, and extend the black radical tradition.” And if I could ask her anything now, it would be… The first question that I am going to ask her whenever I see her again will be: “Did you know that that was a contradiction?” In a way, it has been like Virginia Woolf. Her first novel is called The Voyage Out and her last one is To the Lighthouse. There is this outward thing, and then there is a return. I was sent to school and I began to realise, maybe in between In the Break and the other books… In the Break was published in 2003. My mom died in 2000. Then our first child was born in 2004. I would say, in the wake of my first child being born, I realised that my mom sent me out to do something, and what I found when I got out there was that I needed to go back. Of course, I also found out that I could not go back. So, the only thing I could do was go further out and try to not replicate, but somehow instantiate for someone else some place from which to depart.

I got to a point where it was a great gift to be able to start writing with Stefano, and it was so much more fun and interesting than writing stuff by myself. I also began to realise that the stuff that I was writing by myself was really preparation for teaching, which is to say, more precisely, preparation for common study. I am at the point now where I don’t want to do anything by myself. However, I felt a certain professional obligation to finish those three books that people call a trilogy [consent not to be a single being], even though it is not. It is just a bunch of essays, but it was professionally important for me to finish them, so I could take one further step in terms of my status and getting paid. It was part of the job. Now I cannot get any further professionally, so I don’t have to do that anymore.

And, look, it is with regard not only to the scholarship part of it, but the poetry part of it, too. There is a book of essays which is sort of an accompaniment to the poems that I just read [from perennial fashion presence falling] and I am going to finish that and send that off to the press. But I don’t think I am ever going to have this conscious kind of desire to write another critical book. Then, by the same token, I don’t think I am ever going to write a conventional poetry book again. But I won’t stop writing. It will just be for doing stuff with other people. If there is some textual evidence of it, it would be in the form of notes. I don’t even want to go through the process of publishing it, which I find oppressive at this point. So, if anybody cared about it, I think at this point I would put stuff online or with the poetry. And because I have been given the amazing chance to start working with musicians, especially with the great bassist Brandon Lopez and the great drummer Gerald Cleaver, even the poetry is stuff that is for them, so that I can work with them.

You even did some singing during your poetry reading.

If you want to call it that. Well, there is so much music that is being indexed in the writing all the time.

It feels like a dissolution of form, somehow. Also, the way you perform it. It can be soothing, as it is done in a softening way. Nevertheless, the things that you are saying are very hard, very difficult in a myriad of ways.

I don’t know if it is the first, but the first published critical discourse on African American music that I am aware of, by an African American, was written by Frederick Douglass, in the second chapter of his narrative in 1845. What he said there is still true. He talked about how the songs that the slaves sang could speak of the most horrible experience in the most rapturous tone. They would turn around and speak of the most glorious experience in the most mournful tone. And that interplay of mourning and celebration – Saidiya Hartman uses the terms terror and beauty – is irreducible in what we do. It is irreducible in African American music.

You hear it in Gilberto Gil, Milton Nascimento. It is simply an Afro-diasporic imperative, but it is not even constrained there. You hear it in what I would call – using a sort of loaded word – any authentic music, from Bach to Bessie. Langston Hughes, he got this great poem called Theme for English B [1951], and it is written in the voice of a student at City College, in the form of an essay that he had been assigned by a professor. It is this beautiful poem in which he says: “I listen to music whether it is Bessie, bop, or Bach.” So, everything from Bessie Smith to Charlie Parker. I think part of what is implicit there is that it is not a formulation about his identity, as in: “Oh, my personal identity is complex and expansive enough that I listen to all these different kinds of music.” I think it is really a formulation about music. Real music, authentic music, shares something, and it doesn’t matter the genre. You could put any number of other names there. One of the fundamental things that it shares, I think, is this mix of joy and pain. And it is not half joy and half pain. It is one hundred per cent joy and one hundred per cent pain.

* Fred Moten does not capitalise the word «black» in his writing. We choose to be consistent with Moten’s usage in rendering his answers.