DAt first, admiring Robert Longo’s masterful drawings went quite well. With monumental deftness, confidence, and self-assurance (that I more or less instantly estimated is unbridled), he takes command of Louisiana’s fittingly majestic west wing with his vast pictures standing several metres tall. My prior reservations felt like default settings, which made it all the more important to acknowledge them. Just two years after the museum presented Richard Prince, it now shows yet another old man from the so-called Pictures Generation: a 1970s New York-based movement that veered towards a Pop sensibility you might call conceptually intelligent rather than flashy. (As an aside, I note that the movement also includes significant female artists. For example, it would be spot on for a museum like Louisiana to embark on staging a major Louise Lawler exhibition.)

My initial reservations were also fuelled by some commonplace statements from Longo himself – presented in a Louisiana Channel video and in the museum’s press materials – about the image as a bearer of truth and the artist as some kind of prophet. But, as mentioned, the skepticism melted away when encountering the actual work.

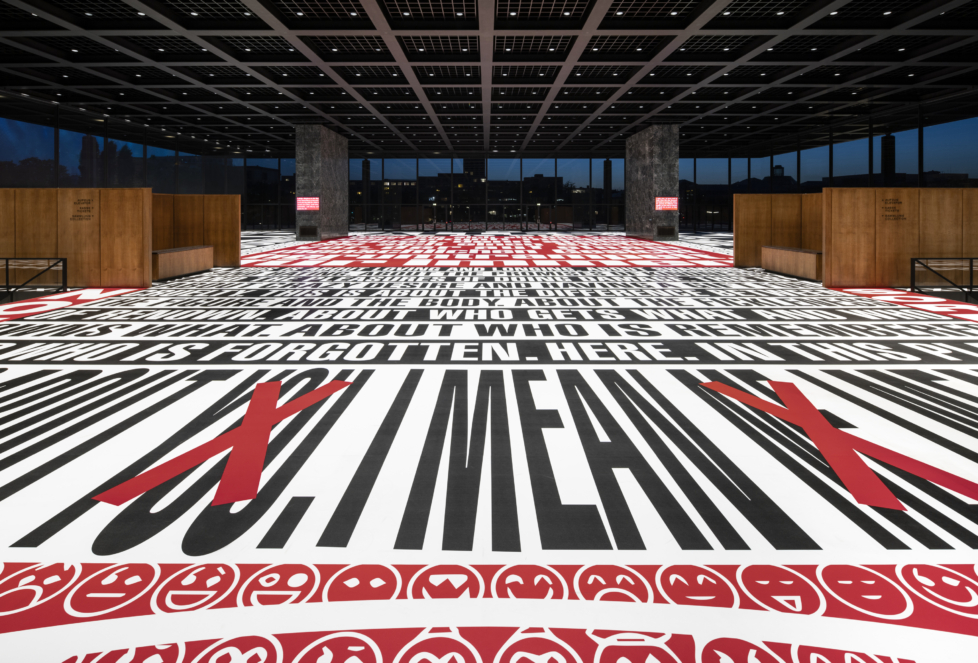

All of the works in the exhibition (perhaps Longo’s entire production?) are in black and white. With few exceptions, they are charcoal drawings on a scale that almost outdoes that of real human beings and landscapes, and the scenes could easily be mistaken for the kind of “reality” we have collectively agreed that photographs represent. Not least because Longo’s drawings are almost always based on existing photographs. So, here we have: huge drawings, meta-representation, an almost perversely precise realism, and monochrome monotony all the way. There’s black and there’s white, and then there’s all the vast grey in between. This simplicity was captivating – initially.

At first, there are the people – four of them – from the series Men In The Cities (1981–1983), which appear to be key-like breakthrough pieces in the artist’s oeuvre. Their poses are contorted (because the drawings depict Longo’s friends evading objects he hurled at them before photographing them). Being contextless and colourless figures conjured up by black on white backgrounds, they above all look like drama. A hint of pain, maybe a hint of performance. As the exhibition’s overture, they are flanked on one side by a highly charged 9/11 motif: two tiny planes heading into a colossus of black (Untitled [The Haunting], 2005), and on the other side by four fiercely enlarged, cathedral-like gun barrels (Bodyhammer, 1993–1994). The gleaming cold metallic surfaces of the weapons, the inky black barrels that feel atrocious to look into, a woman’s detailed knees and ankles sandwiched between stilettos and a skirt of entirely flat darkness. A triptych of terror over Manhattan, where black has devoured most of the image so that what we really note are the death machines slicing through a smoke-hued sky.

Looking at these drawings is quite exceptional. As if Longo utilises the darkness that flows from a charcoal stick and the darkness harboured in our civilisation or minds in entirely corresponding ways. His drawn black is so bleak and artificial and astonishingly real; the colour erects a darkness on paper that simultaneously resembles sculpture and news. I thought about technical virtuosity as a measure of quality; after a century of conceptual art, this aspect feels so sidelined that praising sheer skill almost seems reactionary. And perhaps it is the clear conceptuality also at play in Longo’s work that makes his technical prowess stand out and bulge as an almost numbing talent. He possesses an eye for shadow, a mastery of image, and a patient hand that must be close to unrivalled.

On the far wall of one of the exhibition’s tallest rooms, a steep, tar-coloured sea towers up, boat refugees on top. The frame glass mirrors the image on the opposite wall: a near-forensic close-up of bullet holes in a windowpane after the Krudttønden attack in Copenhagen in 2015, killing one and wounding three. The holes look like screams in ice, and the black sea looks like a murderer because the continent it surrounds is so nauseatingly indifferent to non-continental life. I believe this art to be overpowering and that this in itself is an achievement.

And then: at some point, a slightly tiresome solemnity began to creep in. The virtuosity remained intact, but upon arriving at a temple-sized iceberg (a motif that blatantly venerates Caspar David Friedrich, while also being emblematic of climate catastrophe as such), an eight-metre-long Wailing Wall cast in dramatically animated shadow, and study upon study of the interior of Freud’s consulting room, my initial awe was punctured. Perhaps due to a knee-jerk skepticism toward the outburst of masculinity, that suddenly seemed massive in scale.

Later, though, when Longo himself led a tour through the exhibition, I realised that this punctuation had to do with a sense that his works are not quite what they pretend to be. In his introduction to a harrowing image based on a press photo of Syrian and Iraqi refugees queueing at the Serbian border, Longo pointed out various brand logos on the refugees’ clothing and belongings and declared: “so really, they’re just waiting in line for shopping.” To joke about people at the notoriously brutal threshold of Europe, who are either about to be sent back to their de facto death sentences, suffer the grudging aggression of a violence-prone Serbian border police, or continue on illegally with their lives at stake, was so staggeringly misplaced that it beggars belief – especially coming from someone like Longo who so vehemently claims to have the weight of reality and its cruelties at heart. But his bizarre comment also set off a broader sense of disillusionment towards the drawings that, at first, felt like intensifications of the world – enlarging key moments that captivate the gaze instead of flickering by, as media images generally tend to do.

I’m thinking about how photographs are always surface. How photography and representation are, in some ways, also the polar opposites of reality. How a photograph condenses split seconds that may in fact be far removed from the lived truths it claims to document. These are not revolutionary insights. I consider them true outside the context of Longo’s work – which is, indeed, well worth examining with alert eyes and minds. And while utilising eyes and mind, you can also usefully ponder what reality is and where it resides: a vast, jet-black image can, indeed, be darker than darkness.