“The destruction of Gaza is not only a genocide; it is also a deliberate erasure of history and culture,” architect and historian Nadi Abusaada stated, when I asked him about the situation for Palestinian culture today. On Sunday, 5 October, Abusaada will give a lecture titled “Palestinian Art Before The Nakba” at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo, as part of the discursive program for the 138th iteration of Høstutstillingen, the yearly juried exhibition arranged by the Association of Norwegian Visual Artists (NBK).

An increasing number of people around the world are aware that the Arabic word “Nakba,” which means “the catastrophe,” is a term used to designate the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from their homeland in 1948, on which the state of Israel is founded. Thousands of Palestinians were massacred, and about 750,000 were displaced and became refugees. Today, the ongoing genocide in Gaza is often referred to as a continuation of the Nakba.

Abusaada, who was born in Jerusalem, has done extensive research on Palestinian art and culture, especially that of the 1930s. Currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at the School of Architecture and Design at the American University of Beirut, he has also been involved in curating a number of exhibitions around the world. Abusaada currently serves as Lead Curator for the Permanent Exhibition of The Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, a town north of Ramallah in the West Bank.

I was able to get hold of Abusaada, who was travelling, for an interview by email. I wanted to ask him about his historical research, but also about his perspectives on the role of art, artists, and museums today.

I’m curious to learn about your research and your findings. How would you characterise Palestinian art before the Nakba?

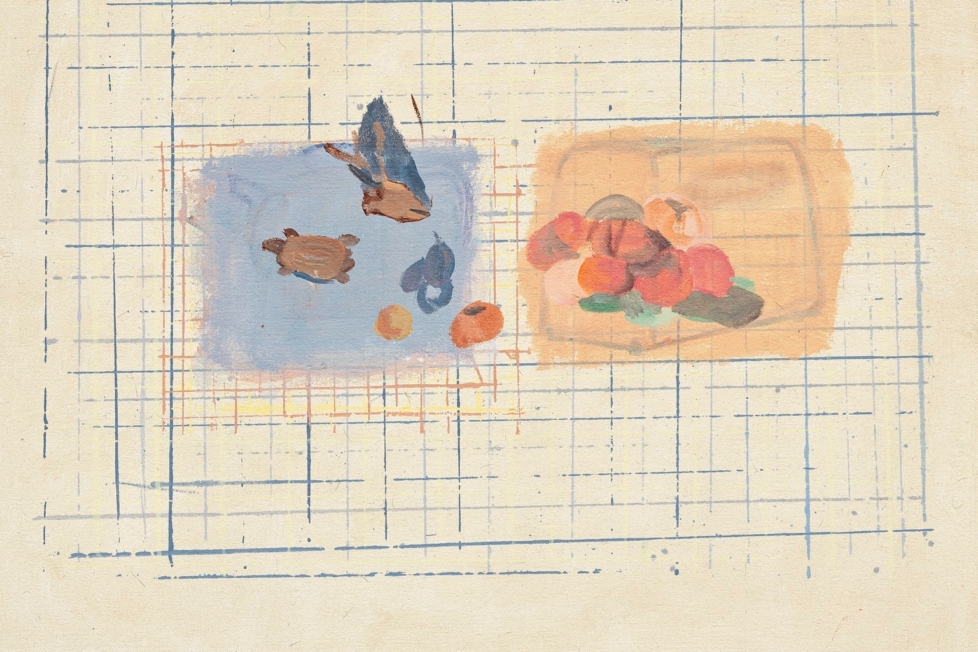

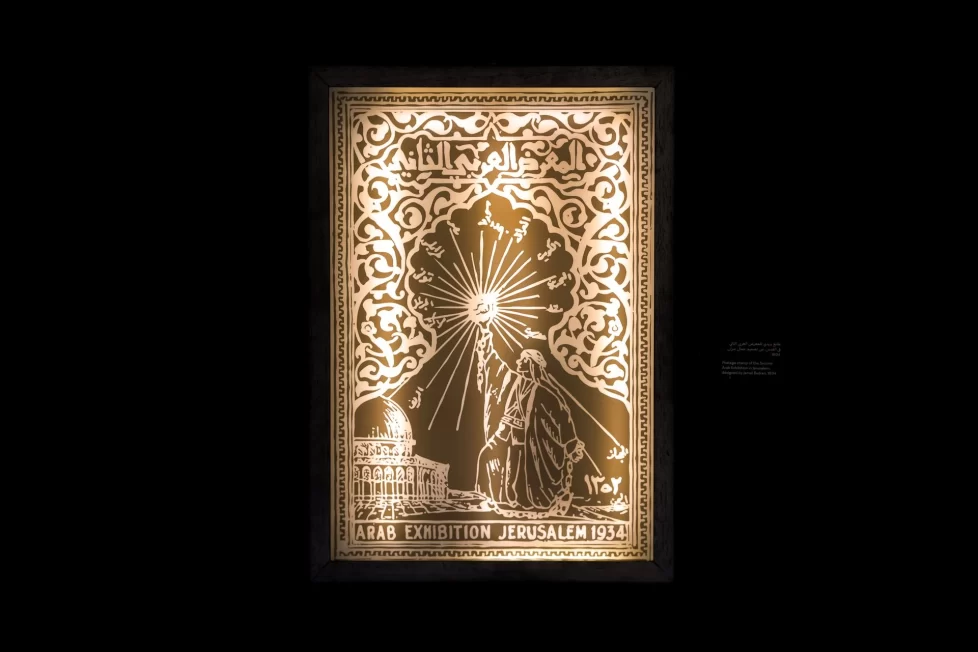

My research has focused on the interwar period, particularly the 1930s, which was a moment of immense experimentation and cross-pollination in Palestinian art and craft. This was a time when new artistic languages were being forged, often at the intersection of modernist tendencies and local traditions. In Jerusalem, for example, artists, architects, and craftsmen were experimenting with exhibitions as spaces to showcase their work – textiles, painting, mother-of-pearl, ceramics, glass – and to imagine Palestine as part of a broader Arab world.

One of my findings is that art in this period cannot be separated from the social and political context. The emergence of Palestinian art was deeply tied to questions of national identity, modernity, and resistance to British colonial rule and Zionist settler-colonialism. It was also tied to regional dialogues: Egyptian, Syrian, and Iraqi artists all participated in Palestinian exhibitions, making these spaces arenas of Arab solidarity.

I would characterise Palestinian art of the 1930s as both experimental and deeply rooted. It was modern, but not in a purely Western sense. It drew heavily on craft traditions, calligraphy, and vernacular forms, yet sought new ways of presenting them. What is tragic is how much of this history has been erased or left undocumented, making the task of recovering and narrating it urgent today.

The ongoing genocide in Palestine has also been described as a culturicide. As a researcher on Palestinian and Arab culture, how do you view the situation?

The destruction of Gaza is not only a genocide; it is also a deliberate erasure of history and culture. Libraries, archives, universities, museums, places of worship, heritage sites, all have been bombed. The scale of this destruction cannot be understood as collateral damage. It is systematic, aimed at severing Palestinians from their cultural memory and futures.

Culture is not separate from life: it is how Palestinians imagine themselves, narrate their history, and transmit knowledge across generations. To destroy that is to attempt to annihilate a people’s capacity to narrate their own story. In this sense, the genocide is also a historicide. It is about erasing pasts and futures alike.

Museums in Norway have issued a joint statement about the importance of protecting cultural heritage in Gaza, but, to my knowledge, they do little to act upon their words. To what extent do you find that the international museum sector supports Palestinian art and cultural heritage? What should the museums be doing, in your opinion?

Most international museums have been slow, if not entirely absent, in their engagement with Palestine. Statements of concern are important, but they are insufficient if not followed by action. At the same time that museums declare the importance of protecting heritage, they remain largely silent on the root causes of its destruction: colonial violence, past and present.

What museums could do is the following: acknowledge and name the genocide; actively support Palestinian artists, scholars, and institutions through funding, partnerships, and acquisitions; provide safe spaces for displaced artists and collections; reconsider their own colonial legacies and investments and how those tie into Palestine. Silence, or mere symbolic gestures, risks reproducing the very erasures they claim to oppose.

You are also a curator at the Palestinian Museum. What are you working on there?

At the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, I am working on the conceptual development of a permanent exhibition that narrates the modern history of Palestinian art, craft, and design. This involves archival research, object selection, scenography, and designing displays that both preserve and activate the material.

The challenge is that Palestinian material culture is dispersed and fragmented – across refugee camps, private homes, international museums – and often in fragile condition. Our work is therefore as much about recovery and reconstruction as it is about curation. We are building a narrative from fragments, insisting that even in dispersion and dispossession, there is a coherent story to be told about Palestinian creativity and resilience.

Importantly, international museums should also directly support Palestinian institutions that are working under extremely difficult conditions, such as the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit. Our institution is doing the vital work of researching, preserving, and exhibiting Palestinian cultural heritage, yet it cannot sustain this mission without tangible international support and partnerships.

How do you see the role of art and artists today?

Art today is both testimony and imagination. It documents what is happening in Gaza, in Palestine more broadly, but it also refuses to let the future be foreclosed by violence. Artists are producing images, sounds, and narratives that insist on Palestinian presence and futurity, even when everything around them is being destroyed.

The role of art is not to provide solace or decoration. It is to make visible, to disrupt, to connect, and to keep alive the possibility of another world. In Palestine, artists have always worked under conditions of rupture, exile, censorship, and destruction. Yet they have always also found ways to create.