The fifth edition of Bergen Assembly is convened (that is, curated) by the Indian artist and environmentalist Ravi Agarwal and the Palestinian writer Adania Shibli, alongside students, faculty, and the administration of the Bergen School of Architecture (BAS). Titled across, with, nearby, this year’s triennial makes a point of being experiential. With a programme of excursions, conversations, workshops, and social rituals, it focuses on collective production and sharing of knowledges. The triennial is underpinned by ideals of the transformative power of art – particularly when paired with activism – alongside a commitment to care and openness towards the unknown. For such a project to succeed, visitors must take part. In other words, Bergen Assembly invites its audience to participate in an artistic think tank of sorts.

Across a range of spaces in and around central Bergen, a diverse gathering of contributors and activities has been set in motion, mostly acting separately from one another. The most far-flung venue is the Textile Industry Museum, housed in the disused Salhus Tricotagefabrik. It lies an hour north of Bergen, reached aboard The Literature Boat Epos – a former library boat recently converted into a floating cultural centre with its own touring programme during the triennial. At the museum, Thai textile artist Jakkai Siributr presents his social art project There’s no place (2020–ongoing). Suspended from the ceiling are numerous colourful patchwork quilts, hand-embroidered with illustrations and inscriptions in different languages that shed light on colonial and nation-state violence inflicted upon Indigenous groups. When I visited, a group of participants who had bought tickets to take part in the embroidery project were seated beneath the textiles. For the rest of us, it was not easy to get a proper view of the quilts, as we were swiftly shepherded past the works. Instead, we were given a (seemingly improvised) tour of the museum’s production halls. It was a strange affair, and I felt I would rather have been elsewhere. For it takes stamina to piece together an overview from the parts that make up the whole, and to do so you need to be in the right place at the right time, and with the right mindset.

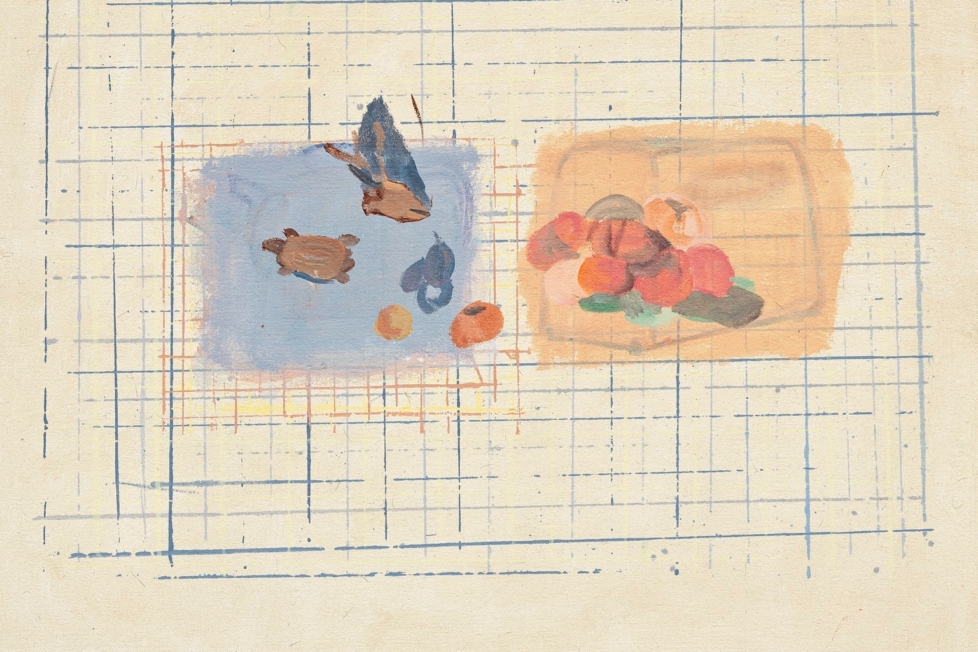

At the artist-run gallery Entrée, the Kenyan collective Maasai Mbili presents a sprawling array of unframed prints and works on paper. Pinned directly to the walls or stacked in piles along the floor and on the windowsill, the presentation of the works appears informal, bringing to mind a Christmas market where visitors are free to leaf through objects and rearrange them. Founded in 2001 in Kibera, Africa’s largest slum on the outskirts of Nairobi, the collective today consists of eleven artists. Their motifs are wide-ranging, spanning from figurative studies of humans and predators through to abstract and meme-like imagery, as well as stylised signage for small businesses. A series of five watercolours, each a variation on the same composition, stands out (Joachim Kwaru, all works untitled). In each, the upper panel depicts white garments hanging from a red washing line against a black background. Beneath single garments, black legs and lower bodies hover in front of a dense cluster of buildings. The simultaneously hopeful and melancholic atmosphere underscores the precarious living and production conditions of the slum.

The main section of the triennial’s exhibition programme is, as usual, to be found at Bergen Kunsthall. Here, each gallery space appears to present its own distinct exhibition with rather unconnected themes. In the bookshop, a teacup spins on a saucer, powered by a hidden motor that reproduces the shifting direction of the wind in real time (Clara Hastrup, Untitled, 2024). Another gallery has been arranged as a listening lounge for East African musical traditions (Singing Wells, Sonic Inheritances). Yet another is devoted to a range of projects exploring sustainable ecologies. Here we encounter Kåre Aleksander Grundvåg’s Earthworks (2021–ongoing), comprising sculptures of 3D-printed clay and soil containing various plants kept ‘alive’ under glass. As the plants wither, the sculptures are to be fired and buried in the ground at the sites where Grundvåg originally sourced the clay.

Indian artist Vikrant Bhise’s painting Memory, Resistance, and Consciousness (2023) is an overloaded composition of body parts and human figures. Its chaotic, claustrophobic atmosphere calls to mind Picasso’s Guernica (1937). A recurring visual element is the emblem of the Dalit Panthers, a revolutionary Indian grassroots movement inspired by the Black Panthers, which was especially prominent in the struggle against the caste system during the 1970s and 80s. In the same room, a total of thirty-seven sketches for book illustrations and other projects – drawings and paintings – by the Sámi artist Iver Jåks (1932–2007) are on display. Despite their number, the works feel surprisingly inconspicuous in this context. It is a clear example of the dissonance encountered throughout the triennial, between the often modest character of the exhibited material and the significance ascribed to it. In a corner is Karen Werner’s installation Night Air (2025): a white shelf with a number of pocket radios for visitors to borrow, alongside a microphone. On sixty evenings during the exhibition period, an invited artist will perform lullabies into this microphone, to be broadcast live over FM radio (otherwise discontinued in Norway) and audible through the radios. This simple project is gentle and warm, and perhaps the one that makes the triennial’s title resonate most clearly.

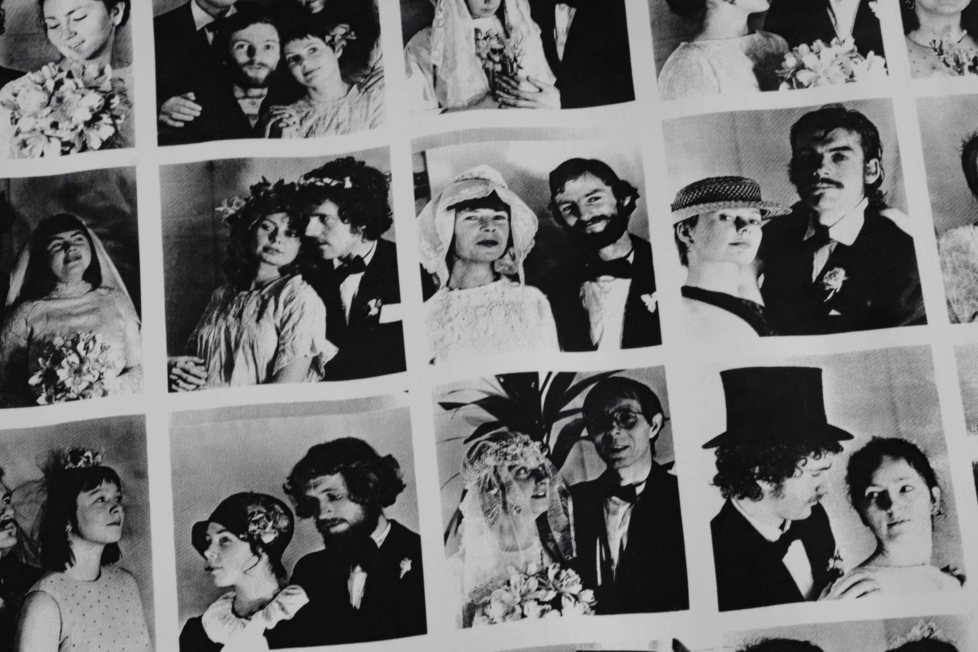

A common feature across the exhibitions, at the kunsthalle and elsewhere, is the invitation to delve deeper. This often necessitates the catalogue’s authoritative explanations for a meaningful whole to emerge. The many cryptic contributions from artists and collectives associated with the Indian platform AgriForum (Acts of Re/Collection) stand out as particularly dependent on this kind of textual support. Elsewhere, the connections between works are more immediate. This is the case, for example, in the largest gallery, which is dedicated to the Bergen-based collective Gruppe 66, with works on loan from the neighbouring institution Kode. Videos with documentation, archival material, and slideshow presentations help to contextualise the group in relation to its seminal exhibitions of the 1960s and 70s.

Group member Laurie Grundt (1923–2020) is represented by two somewhat iconic paintings: Hippie Politi (1972), which depicts the violent arrest of four naked bohemians, and the more abstract Menstruasjonsbilde (Menstruation Painting, 1966), incorporating bottle caps, nails, and a masonry brush. Elsebet Rahlff features most prominently, with a series of textile works, among them six peculiar hats (1970) and a large red uterus (Livmødre, Uterus, 1977). This work is suspended from the ceiling above Trond Kastmann’s Pute- og dynetrekk (Pillow and duvet covers, 1977), a blue bed frame dressed with a red sheet and bedding decorated with symbols for lesbian, heterosexual, and – predominantly – male homosexual coupling. During the opening days, Rahlff also unveiled a new work, all we are saying (2025), comprising multiple white pennants mounted on the deck of the already mentioned literature boat.

At the kunsthalle, the group’s use of the “Co-ritus” method is foregrounded. Inspired by Scandinavian Situationism, this method is a relational practice that actively involves the audience in the production and presentation of art. On four occasions during the triennial, invited artists will stage performances based on this model. So far, two have taken place, the most recent of which was led by Kevo Stero, one of the founders of Maasai Mbili. The performance took place inside a colourful makeshift playpen filled with games, blackboards, drawing materials, and a spinning wheel suggesting topics of conversation. I was among roughly twenty attendees (including a baby and a disproportionate number of Assembly staff) who were encouraged to share “newly acquired knowledge” about the city of Bergen. However, I found it too awkward to take an active part, and perhaps in so doing contributed to the session being less than a resounding success in terms of meaningful knowledge exchange – at least for me.

Next up is the aforementioned Jakkai Siributr, followed by the Oslo-based collective Tenthaus. The latter is also represented in the triennial with a mobile studio parked outside Bergen Cathedral School, where The Communist Museum of Palestine is running a discursive programme and receiving contributions from artists and the wider public. In time, the museum will present a dispersed exhibition across the city. Precisely how the project is organised or intended to take shape is still unclear to me, but it is the process initiated by the triennial that I most look forward to following.

In the catalogue’s introduction, the convenors of the triennial ask how best to challenge exclusionary learning practices in ways that uphold diversity, justice, ecological sustainability, and economic redistribution. The concepts of neighbouring, care, and love are proposed as tools for this sympathetic agenda. Rather than focusing on what to call such collectivist ideals, this year’s Assembly is concerned with how these principles are to be put into practice. Given the ambition to set things in motion, it is difficult to determine whether the triennial’s aim of creating new forms of care-based knowledge exchange is, in every case, intended to yield something tangible. This uncertainty, however, seems to be a feature rather than a bug. It may, in fact, be an effective way of encouraging visitors to take responsibility for the success of the think-tank experiment and thus – hypothetically – of asking us to join in.

The triennial is spatially decentralised and demands effort. At its centre is the activation of the public through a continuously unfolding programme of performances, tours, happenings, and conversations. It is less about the display of art in the traditional sense than about inviting us into a collective search for new strategies to address the world’s many urgent challenges. To what extent, and in which settings, the audience is expected to contribute to this work is not entirely clear. Previous editions of Bergen Assembly have been criticised for addressing themselves primarily to art professionals. But is it really an issue that the triennial requires an investment from the visitor? In principle, everyone is welcome to engage in its fleeting experiment in community. You must, however, equip yourself with the kind of capital required to participate. This year, the price of admission is curiosity, time, and a willingness to take part.