I de første årene av karrieren, før de har fått opprykk til den globale kunstmaskinens mer veloljede nivåer, er kunstnere ofte å finne på et Ryanair-fly på vei til mer eller mindre komfortable losjier, stilt til rådighet av mer eller mindre bemidlede organisasjoner på mer eller mindre perifere steder – såkalte «residencies». Selv om det varierer hvilke ressurser som tilbys, representerer disse oppholdene likevel viktige brikker i mange kunstneres profesjonelle dannelsesforløp. I Oslo har det ikke akkurat florert av slike tilbud, i hvert fall ikke med noen særlig grad av synlighet, og som har vært åpne for en større krets av uetablerte kunstnere. Når Oslo-baserte PRAKSIS i dag, mandag 21. mars, starter opp sin første runde med residencies, er denne æraen offisielt avsluttet.

PRAKSIS har ikke noe fast tilholdssted, forteller initiativtager, den britiske kunstneren Nicholas Jones, til Kunstkritikk, men skaffer tilveie lokaler etter behov, gjennom et samarbeid med andre organisasjoner basert i Oslo, som PNEK, Notam, Atelier Nord ANX og Oslo Pilot. Integreringen i det lokale kunstlivet gjenspeiles også i det uvanlige grepet å åpne for deltagelse fra kunstnere allerede bosatt i byen. Deltagerlisten ble offentliggjort tidligere denne måneden. Her finner man de norske kunstnerne Maren Dagny Juell Kristensen, Eli Maria Lundgaard, Tonje Alice Madsen, Marit Pethsiri Silsand, i tillegg til britiske Gary Zhexi Zhang og kanadisk-italienske Martina Petrelli.

Også spesielt for PRAKSIS er at de har erstattet den selvstendige atelierpraksisen som oppmuntres de fleste andre steder, med et temaspesifikt workshop-format, ledet av såkalte «lead-residents». Først ut av disse er de britiske kunstnerne David Bandy og Larry Achiampong, som skal lede overnevnte deltagere gjennom et månedslangt program med temaet New Technology and the Post-Human. Utover året vil PRAKSIS arrangere tilsvarende opplegg i samarbeid med Seamus Harahan, Martin Creed og Smadar Dreyfus.

Kunstkritikk har bedt Jones fortelle litt om PRAKSIS’ konsept og bakhistorie. Intervjuet er gjengitt på originalspråket.

Can you say a little bit about what PRAKSIS is and the idea and people behind it?

Of course; our activity centres around a thematically led residency programme that looks to bring local, national and international artists, makers and thinkers together in relationships of collaboration and exchange. Alongside the residencies we run associated events that aim to offer insight into the practices of our artists. I co-founded PRAKSIS as a not-for-profit in 2015 with Rachel Withers and a lot of help from my partner, Charlotte Teyler. Rachel is an established art critic and the Head of History of Art and Design at Bath Spa University. She assists me with PRAKSIS’s conceptual design, forward planning and organisational networking. Charlotte’s background is in International Relations and she previously worked for a think tank in London. She has been instrumental in researching, coordinating, and project managing throughout the developmental stage of PRAKSIS.

My enthusiasm to establish PRAKSIS grew from my own experiences of residencies, teaching and learning. When I graduated from my MFA at the Slade School of Fine Art in London in 2011, I was nominated for a travel scholarship and at the same time invited to participate in a residency in Florence (Italy). An incredible year and a half followed, during which I spent time on residencies in Italy, Japan, China and Switzerland. When I got back to the UK, I was invited to tutor at several universities and this got me thinking more about how artistic practices develop. I felt that residency programmes offer a great deal in terms of artistic, personal and professional growth, and started thinking about the structures involved in traditional models of education – about the relationships between tutors and students, about critiques, group discussion and peer-to-peer learning and so on – and I felt that if some of this structure could be brought into the 24/7 intensity of a residency an incredible environment for development and cross-cultural experience could be created.

Is there any particular reason why you chose Oslo as the location for PRAKSIS?

I had some prior connection with Norway, but when the idea for PRAKSIS started to form I was quite happy living in London. Discussions I started having about the idea drew great enthusiasm from artists and educator friends, but I wasn’t sure how or where I could turn it into reality. Then in 2014, I came across an open call in Aftenposten for proposals for buildings on an island in Oslo Fjord that looked ideal. The open call was in fact eventually cancelled, however it led to the beginning of my research into residencies in the Oslo area, and discussions with Oslo Kommune, Kulturådet and locals about whether this was an idea that could work here. Norway has a number of good residencies that are open to application from international artists on an ongoing basis, but there weren’t any in the Oslo area, and everybody I spoke to seemed to feel that there should be. I was drawn by the vibrancy and enthusiasm of arts organisations here in Oslo. I thought there was a strong art scene but felt there was the space to introduce a residency programme that could work with, and offer something to organisations and individuals here, as well as becoming part of raising the international awareness of the scene.

The current form of PRAKSIS has developed a lot from my initial ideas. I went through a research and development period where I spoke with a lot of advisers: artists, curators, educators, residency directors and other arts professionals, both locally and internationally. Through these consultations the formats of working nomadically, involving local and national in addition to international residents, and collaborating with existing organisations were developed, all of which aim to increase PRAKSIS’s integration and benefit to Oslo.

From what I can gather your residencies unfold like extended workshops, structured around a key theme conceived by a specially invited resident. This is quite different from how artist residencies normally unfold, where the artist is set up in a studio and is mostly left to themselves, except for the occasional curator visit. How, precisely, does a PRAKSIS-residency play out? Is PRAKSIS in any way conceived as a reaction to the traditional residency format?

As mentioned I participated in a number of residencies myself, and they were all based around the format you outline. The residencies that I got the most from were the ones with other residents – we had great conversations and I made friends that I still value today – but overall it did feel like given all that was offered an opportunity was missed to further the benefit even more.

As you suggest, with a PRAKSIS residency we invite an established arts professional to lead each residency. They discuss ideas and interests with our team and the nature of the residency is developed with them, for example whether the focus is on production or research. During our initial stage, where we are running nomadically and testing our model, location and the nature of the facilities involved are also factors that get discussed. The lead-residents develop a theme around which to focus the residency community and accompanying events. An open call then draws together a residency community of local, national and international participants. Who will be eligible for the open call is also discussed with the lead-resident. So far they have all decided to make them interdisciplinary.

Being open to local participants is quite unusual as far as residencies go, but I feel this will be a very important aspect of our operations. The idea is to directly benefit locals by including them in our activities, but also to benefit the international participants by introducing them to a local network and knowledge. This situation of working and socialising alongside each other for the residency period will hopefully lead to longstanding friendships and working relationships, at a level that is difficult to form from “the occasional curator visit” as you put it, particularly when brought together around the shared interest created by the theme.

The residents all share a studio space to encourage dialogue – the exact facilities may vary from residency to residency, but are outlined prior to the start. In the case of our first residency, it’s fantastic for us that Notam have provided the facilities for the group. International residents are provided with accommodation, while local residents commute from home. Food is an important aspect of PRAKSIS’s activity, being a point around which to bring people together for discussion and relationship building. We cater lunch each day at the studio and hold a residency dinner each week with invited guests. In the longer term PRAKSIS is working towards offering a fee to all participants so that all can dedicate themselves fully to the experience without the concern of financial burden, but we aren’t at that stage yet.

We also host a number of events each residency which range from seminars and performances to “meet the residents Q&A sessions”, to “drop in critiques” and studio visits for local artists (not participating in the residency). Generally our events are held in collaboration with existing spaces. Our upcoming events held alongside Blandy and Achiampong’s New Technology and the Post-Human residency will take place at Notam and Atelier Nord ANX, with support from PNEK. We’ll work with Oslo Pilot when Seamus Harahan comes to town from May to June, and when Martin Creed joins us in September we will work with Ultima and NyMusikk.

Although all of the lead residents announced are artists, in the “about” section on your web page you also mention that you are drawing in contributions from people outside of the visual arts, you mention “IT-specialists and individuals seeking refuge in Norway’s capital city”. What sort of contributions are we talking about here? Are the actual residencies reserved for artists? What are the criteria you use when you elect participants?

The nature of the participants in each residency is decided in conversation with its lead-resident, but as I mentioned briefly in general they are interdisciplinary, so can include artists, designers, writers, musicians, dancers, curators, anthropologists, and anyone else with a relevant interest and experience in the theme. In selecting participants the main factors we consider are the relevance to the theme and their likelihood to benefit from and to contribute to the residency. Age, academic or professional background are not important. We are looking to bring together rounded groups that will have a range of experience, leading to interesting dialogue and debate.

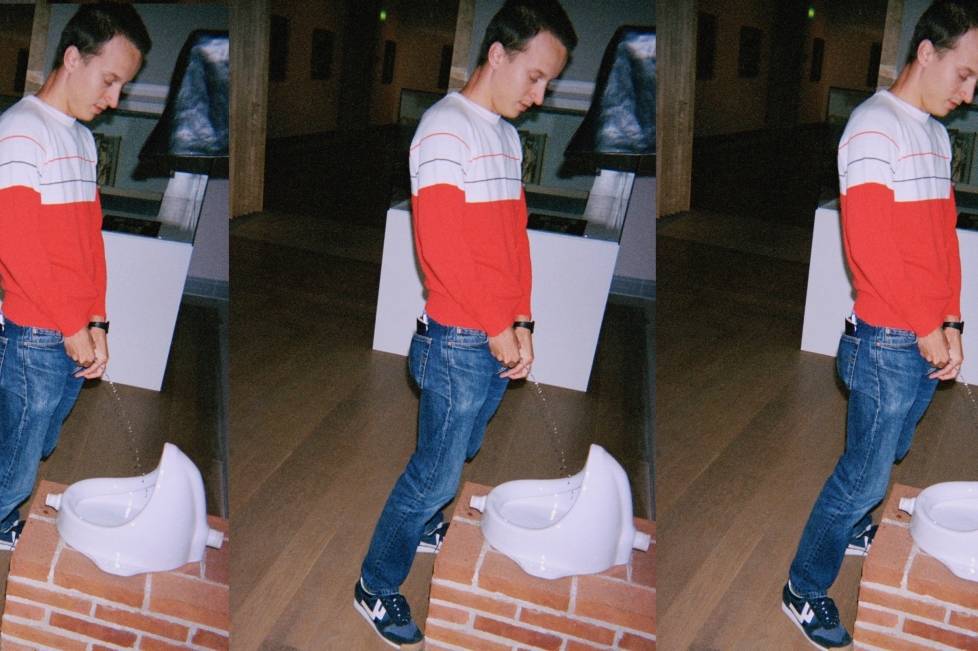

In relation to your question about drawing from people outside of the visuals arts, depending on the interests of the lead-resident and on the theme that is developed, we create opportunities for residents and members of the public to work together (outside of our public events). In the case of David Blandy and Larry Achiampong, they will work with paperless migrants based in Oslo (whom we contacted with the help of organisations such as NOAS and Mennesker i Limbo) to make a new film by modifying the in-game engine of Grand Theft Auto V with the help of Oslo based programmer Jonathan Ringstad. The film will interweave stories of identity and migration to address cultural history and social change, highlighting the experiences of some of Oslo’s more vulnerable residents.

At the moment the collaborations that we have in place are with arts organisations but PRAKSIS is also considering the potential of partnering with non-arts organisations that would benefit from working with artists for an extended period.

What is your strategy – your emphasis on collaboration and non-art-specific contributions – responding to?

PRAKSIS’s strategy comes in response to a world in which the arts and arts education is increasingly marginalised, artists are expected to be more and more professionalised, and also where the majority of people are highly removed from any sense of what artists actually do. It comes from the belief that artists can engage with society and their location in a way that creates active change, while at the same time believing that it is important to support people who quietly explore their own obscure interests without concern for finance or success.

Part of what we do at PRAKSIS is to facilitate the projects of established artists in Oslo, connecting them with suitable organisations and individuals. Through our events, we also look to offer opportunities to local arts professionals, as well as introduce the public to issues surrounding each theme, and the practices of our residents. PRAKSIS aims to address artistic practice – so ideas and processes – offering insight into what drives artists, rather than focusing on the final products that the public normally engage with through exhibitions. With each of these facets of our activity, the residency is at the centre. It provides a place for the lead-residents to develop projects, a resource around which to facilitate events, but at its core it is a place for practices to grow both practically and professionally.

The crossing of traditional social and professional boundaries that PRAKSIS opts for, makes dialogue key. Do you expect it to be a challenge to make these temporary, creative communities work together? What are the measures of success?

You’re right, dialogue is key to what we are doing. In many ways it is what we are doing – setting up situations for focused, directed research, dialogue, debate, production and exploration.

A number of aspects of our programme are as far as I know untried and so I expect there to be a lot of challenges that I don’t expect, and there are already quite a few I do. I am interested to see how well the residency community will function as a conduit for development and exchange, in particular how well the residents commuting to the residency space will work, and whether there will be issues with the group not being together enough. However, I believe that in applying to be part of this experience the participants have all chosen to dedicate themselves to the experience. We have organised a schedule that puts in place some basic structure, but have aimed to leave space for residents to self-organise activities and I encourage this to happen.

2016/17 is our initial test and evaluation period and the programme has the flexibility to adjust as we find out what works and what could be better. Each residency will have two feedback sessions, one at the beginning and one at the end of each residency. These will address resident aims and expectations, practicalities, overall experience, suggestions for improvement, and discussion of what participants feel the residency has offered, as well as whether they feel they have developed as a result of the experience.

In terms of success, in the shorter term of course it would be great if we get a lot of people coming to and benefiting from our public events, but for me personally, our real success will become more apparent over time. I look forwards to seeing how our residents engage with the programme, what changes develop in thinking and practice, what they go on to do after the residency, and what collaboration and international exchanges are born as a result of being part of PRAKSIS.