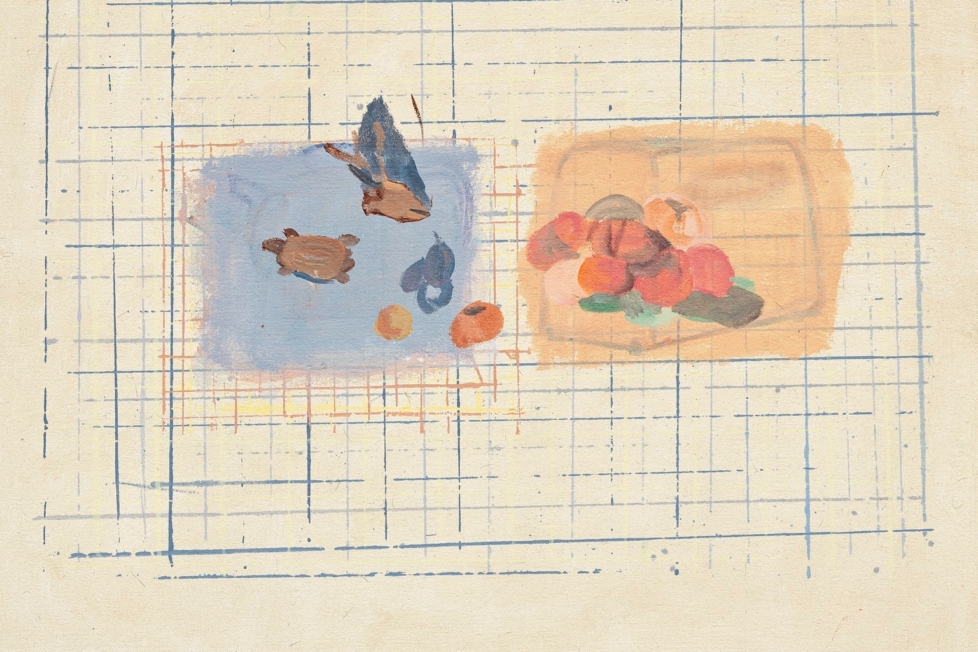

My immediate impression of Steinar Haga Kristensen’s exhibition was that I’d stumbled into a ornamented cornucopia overflowing with painterly delights. Gradually, the experience morphed into something else and I began to feel as though I’d wandered into a mysterious labyrinth.

In the exhibition, a maximalist sensibility in the spirit of the Baroque is balanced by the mathematical simplicity and precision of the installation. This points to the fundamental dialectical view on which Haga Kristensen’s project rests. The ability to see both the right and wrong of the same phenomenon, and the tragicomic absurdity of the human struggle, find their counterpart in the way each structural element in the show is consistently repeated twice. Minor displacements prevent the impression of mechanical repetition and instead allow a dialogue to emerge. Most things are not quite what they initially appear to be. Where this dialectic ultimately leads, however, remains unclear. We are left to decide for ourselves, in the field of possibilities that opens in the fissure between reality and imagination. As is apt for a monographic, mid-career retrospective, the exhibition raises more questions than it answers.

The institutional framing for the exhibition is Kunstnernes Hus, with all the expectations and layers of meaning that entails. The exhibition begins on the staircase leading up to the galleries: Per Krohg’s 1932 fresco, An Artist’s Thorny Path Towards the Heights, has been covered up. In other words, there is an invitation to begin afresh, with a blank canvas. And yet, Haga Kristensen’s fundamental inclination towards dialectics and doubling is already expressed here. His exhibition as a whole can be read as a response to the artistic vision represented in Krohg’s concealed piece. Krohg explores, in mythological form, the idea of art as a skill acquired through the exercises of the academy, while also positioning art as both mirror and critique, in the form of truthful images and distorted reflections of reality. Haga Kristensen’s exhibition may be seen as a contemporary response to such a view of art.

Krohg then, and Haga Kristensen now, create pictorial narratives in the sense that they draw on visual codes and conventions embedded in our language about art and weave them into a narrative structure. Another point of connection is that both artists present as cosmopolitans with a regional accent: Krohg, with classical and French influences as the pillars of a figurative symbolic language; Haga Kristensen, with a visual vocabulary that synthesises elements from Norwegian art history, Italian Baroque and Mannerism, Central European Expressionism, interwar Norwegian painting, and German and Austrian Expressionism. But in the case of Haga Kristensen, all of this rests on the conceptual foundations of contemporary art.

The structure of the exhibition is shaped by the architecture of the building itself, with its two long, skylit galleries. As you ascend the stairs and enter, you are met by a partition wall designed to resemble the interior of a timber cabin, inside of which a couple embraces. They stand in a chaos of fragments, where one can make out, among other things, a lamp base adorned with an acanthus pattern. This object recalls how, during the interwar period, the upper classes developed a taste for decorating houses and hunting lodges with what was seen as typically Norwegian, such as rosemaling, a traditional Norwegian folk-art style of decorative painting, and wood carving, often carried out in freestyle by artists who had roots in modernism.

In the next section of rooms, the walls are crafted as iconostases, or image walls reminiscent of those found in Orthodox churches, where sacred space is divided so that the choir and nave function as separate zones with different purposes and varying degrees of access for clergy and ordinary churchgoers. During the vernissage, a choral work was performed by singers positioned behind the wall, their heads visible through carved openings. When not in use, these openings are covered by masks. The repurposing of medieval forms and traditional Norwegian folk painting is given a third layer of temporal displacement through the inclusion of a Baroque reference alluding to Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling as the ultimate model. The references to Christian art transform the installation into a commentary that is at once profound and humorous, addressing the fact that contemporary art, among other things, has become a surrogate for religion.

When moving through the exhibition spaces, a sense of temporal progression is established in the viewer’s reception, where the doubling of all elements, the possibility of taking different routes through the works, and the ability to adjust the pace of engagement generate new associations and layers of meaning. The many art historical references to different styles and iconographies support the idea that changes in style are visualisations of historical shifts and epochal transitions. Style is never detached from the era in which it emerges. An older critic might wonder whether this is a return to the hectic, unruly, multifaceted, and postmodern 1980s, but at that point in time, Haga Kristensen was still in nappies.

Within the artist-run segment of the Norwegian art system, Kunstnernes Hus occupies the upper echelons. In earlier times, being granted a solo exhibition at “the house” was regarded as the highest form of peer recognition. Many artists have struggled when faced with the monumental skylit galleries, originally designed for the display of large-scale paintings and sculptures. Masters ranging from Pablo Picasso to Arne Ekeland and, more recently, Joseph Kosuth and Vanessa Baird have succeeded in bringing these rooms under the sway of their artistic vision. Now, Haga Kristensen joins their ranks. This is the league he has entered.

Haga Kristensen moves effortlessly between media such as painting, printmaking, sculpture, set design, video games, animation, and musical theatre. Experiencing this multiplicity of forms, genres, and media is part of what generates an underlying sense of unease when encountering his artistic practice. The strength of the work lies precisely in his ability to sustain tension while balancing order and chaos, construction and collapse, both within individual pieces and across the project. If you run Haga Kristensen’s images through image recognition software, a torrent of artworks and artists appears – enough to overwhelm even the most obsessive and eager art nerd.

The flood of images we encounter throughout the exhibition is firmly rooted in a Western art historical tradition inflected with a local palette. This approach can be traced to the two institutions where Haga Kristensen received his training: the art academies in Oslo and Vienna. Faced with this, multiple references spring to mind for the art historian. From the Norwegian team: Edvard Munch, Gustav Vigeland, Arne Ekeland, Per Krohg, Håkon Bleken, Sverre Bjertnes, Bjarne Melgaard, and Trude Viken. From the Austrian side: Egon Schiele, Maria Lassnig, Alfred Hrdlicka, R.B. Kitaj (yes, he studied in Vienna), Hermann Nitsch, and Elke Krystufek. You may get the sense that the exhibition is grounded in a simulation of art history, where notions of authenticity, sincerity, and subjective experience are at play – and at risk of dissolving into a new reality, perhaps ushered in by AI, in which the very notion of what matters, and what is relevant to the experience of being human, becomes a fragile one indeed.

Note: Kunstkritikk’s Norwegian editor, Stian Gabrielsen, authored the exhibition text for Steinar Haga Kristensen’s show at Kunstnernes Hus. We have therefore commissioned an external writer to review the exhibition, and Gabrielsen has not been involved in the editing process. Øivind Storm Bjerke is Professor Emeritus of Art History at the University of Oslo.