I’ve never really felt there to be a crisis in art criticism. It’s more that there’s a lack of interest in making it more engaging. But since I have often read renowned critics announce the end of the genre – mainly because the art market is so decisive in determining what is perceived as relevant that criticism either becomes incompetent or simply no longer in demand – I realise that there is something in our way of understanding art criticism that makes it vulnerable to change. I wonder if this vulnerability comes from the fact that we have, in a deep and perhaps unconscious way, made artists’ careers the primary object of criticism – and that that object has now slipped out of our hands.

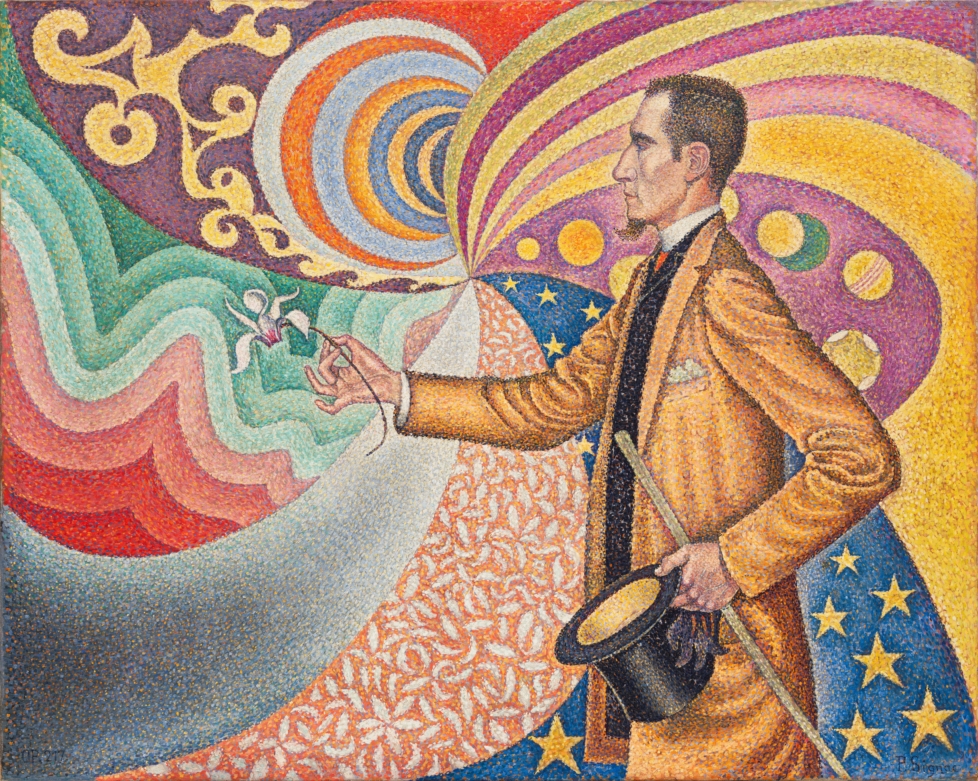

Artists’ careers began to be foregrounded in criticism around the same time that Impressionism emerged in France in the 1870s. According to Harrison and Cynthia C. White’s classic in the field of sociology of art, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (1965), the work of art was replaced as the central subject of criticism at the same time as “the dealer-critic system” superseded the Academy as the central authority in the art world. At that stage, the critic was transformed from a primarily descriptive and evaluative external observer into a figure who, through their interpretations and value judgements, was involved in the very production of their objects, which the Whites call “careers.”

This concept of career includes both the internal development of the artistic practice in question, and the corresponding movement in the public sphere of the art world, so that the most advanced art was given the most prominent placement and the highest price tags. This was achieved jointly by critics and dealers. The idea of career also opened up new horizons for both the market and criticism, as both were given room for speculation. A work did not have to stand on its own merits, but could be described as part of a promising artistic career. Critics could then basically sprint ahead and speculate about the future, and buyers could take a gamble that the work would increase in value as the career progressed.

Broadly speaking, the criticism that emerged then is the same as what we write today. What is presented is essentially a trajectory of development. A given work should be interpreted as an extension of or departure from a pursuit that has been present in previous works by the same artist, or possibly those of other artists. The critic traces the artist’s trajectory through the art world, understood both as an institutional, social environment and as a certain canon of knowledge and references in which the artist seeks to assert themselves. Therefore, it may also be appropriate to mention the schools the artist has attended, where they have exhibited, perhaps with which other artists. And, of course, their place of birth, where they live, gallerist, gender, ethnicity, and sometimes age. All of this is necessary in order to bring the critical object to the fore: art understood as the coming together of internal and external development, practice and career.

It’s not a bad idea – as long as you actually believe in progress. I think White and White’s description of the new criticism best describes what was happening in the United States around the same time they were writing their book, in the 1960s. From the 1940s onward, Clement Greenberg had influentially argued that each art form strove for medium-specificity – that painting, for example, sought its pure form. The extent to which an artist’s career could, over time, contribute to the development of an art form itself, put it on a path to securing a spot in a future canon. It was the critic’s task to identify what we would today call the ‘relevance’ of the artist’s work and to publicise it so that the artist could be granted a corresponding place in the art world.

Today, however, the idea of development is no longer the dominant doctrine. Quite the opposite. It is sometimes claimed that contemporary art emerged with the fall of the Berlin Wall, when the idea of development was replaced by the idea of globalisation. Contemporary art criticism was understood at the time as arising from the realisation that traditional artist-centred criticism of the Greenbergian type was no longer viable.

Yet, we continue to write criticism according to the Whites’ career model, even though the idea that there is a connection between the two sides of a career – between the development of an artistic practice and the artist’s position in the art world – can’t be taken for granted. What makes art worthy of attention today is not how it relates to what is most artistically advanced, but rather how it relates to what is currently considered relevant in the art world.

One could perhaps argue that the intermediary role between the artist and the artwork is now occupied not by the notion of career, but by some agent within the art world (the curator, for example, but hardly ever the critic). It is this intermediary – the prevailing agenda, perhaps – that our criticism most often ends up addressing, even as we claim to be writing about art, following the model introduced with the “dealer-critic system.” In this way, our object has gradually slipped out of our hands, and our task risks becoming simply evaluating how well an artist has adapted to the conditions that promote a successful career. Under such circumstances, interpreting art becomes, in practice, no more than the production of ideology with the sole function of legitimising how careers are created within the art world.

When even the most sincere and altruistic art risks being perceived as a career move, the idea of career works as a poison, even for art itself. All it can represent then is a path through the art world. Based on this description, I can obviously also recognise that criticism is in crisis. If there is any truth to the idea that the vulnerability of criticism stems from the focus on careers, it’s easy to understand why it has become irrelevant and undesirable. I don’t know whether the Whites would see criticism as having played out its historical role. Perhaps they would view today’s criticism as atavistic, an adaptation to production conditions that no longer exist and therefore something that should disappear. Personally, I think that criticism, in order to survive on its own terms, must figure out how art should be understood in order to be an object of critical reflection at all. Rather than being in crisis, it actually sounds to me like quite a promising moment for criticism – perhaps even a golden age – if only it could show a little more confidence and initiative.