This autumn, the Swedish art world finds itself caught between crisis and content. In a culture shaped by the compulsive consumption of disaster, outrage, and performative empathy – the question is no longer just what is being shown, but how we look. Or whether we even can.

The 13th Gothenburg Biennial, curated by German-born Christina Lehnert, engages with the conflict-ridden present by showcasing some twenty artists and collectives. Yet, the press release hovers, unspecific and overloaded with abstract ideals about ”resistance”, «solidarity”, and «care», mirroring the emotional flattening of doomscrolling: urgent themes, disconnected from form or context, that numb more than they provoke.

Playa! Art as Poetry in the Nordics at Bonniers Konsthall appears, by contrast, as a pointed rebuke to institutional zombie-prose. Curated by Director Joanna Nordin, and featuring fifteen or so Nordic artists, it foregrounds art’s insurgent capabilities. Of course, whether ‘the poetic’ constitutes a real rupture or merely recycles a worn aesthetic trope is up for debate. Still, the show’s playfulness – with a zany layout by artist Alfred Boman, poetry readings, and a hidden bar by the artist group coyote – suggests a longing for experiences that can’t be scrolled past.

Before her passing in May, the Cameroonian-Swiss curator Koyo Kouoh completed When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting. After traveling to several institutions around the world, it will be on display at Liljevalchs in Stockholm this autumn. With over 150 artists from twenty-six countries, it is a comprehensive reworking of art history that resists the flattening gaze of the feed, moving against the grain of digital attention economies.

Interestingly, many of this autumn’s key artists – from Pipilotti Rist at Accelerator to Claudia Pagés at Index and Nicole Khadivi at Uppsala Art Museum – are working with moving images. And perhaps none more intensively than Lina Selander, who presents no fewer than eleven new films at Marabouparken. The show marks her return to exhibitions after a relatively quiet decade, burrowing into worn-out images as a metaphor for our weary present.

The art festival September Sessions also embraces time-based media. Curated by the Berlin duo anorak, its four-day program, ‘Houred Time’, stretches across Stockholm venues inviting viewers to slow down with works by artists like Annika Eriksson, Nour Ouyada, and Jules Reidy. Indeed, if video art is making a comeback, might it not be precisely because it demands the time and presence so challenged by today’s fragmented attention?

At Moderna Museet, the programming often feels inconsistent, as if responding more to popular demand than artistic vision. Following this summer’s Britta Marakatt-Labba retrospective – the first solo show ever by a Sámi artist at the Stockholm institution – the museum will showcase the Norwegian-Sámi sculptor Aage Gaup (1943–2021). The fact that the show will be the largest presentation of Gaup’s work ever, does not make it less belated. Meanwhile, Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) is back in an exhibition focusing on his later, freer years. Might we see a follow-up presenting the contemporary painting boom of recent years? So far, Moderna Museet has largely ignored it, and its halls have lacked recent painting’s urgent energy.

The museum’s broader problem seems systemic. Is it fear of taking risks, or simply a lack of curatorial direction? Either way, things won’t improve after the Swedish right-wing government’s decision to merge Moderna Museet with the Public Art Agency Sweden and ArkDes – a bureaucratic move that promises even less flexibility and more top-down control.

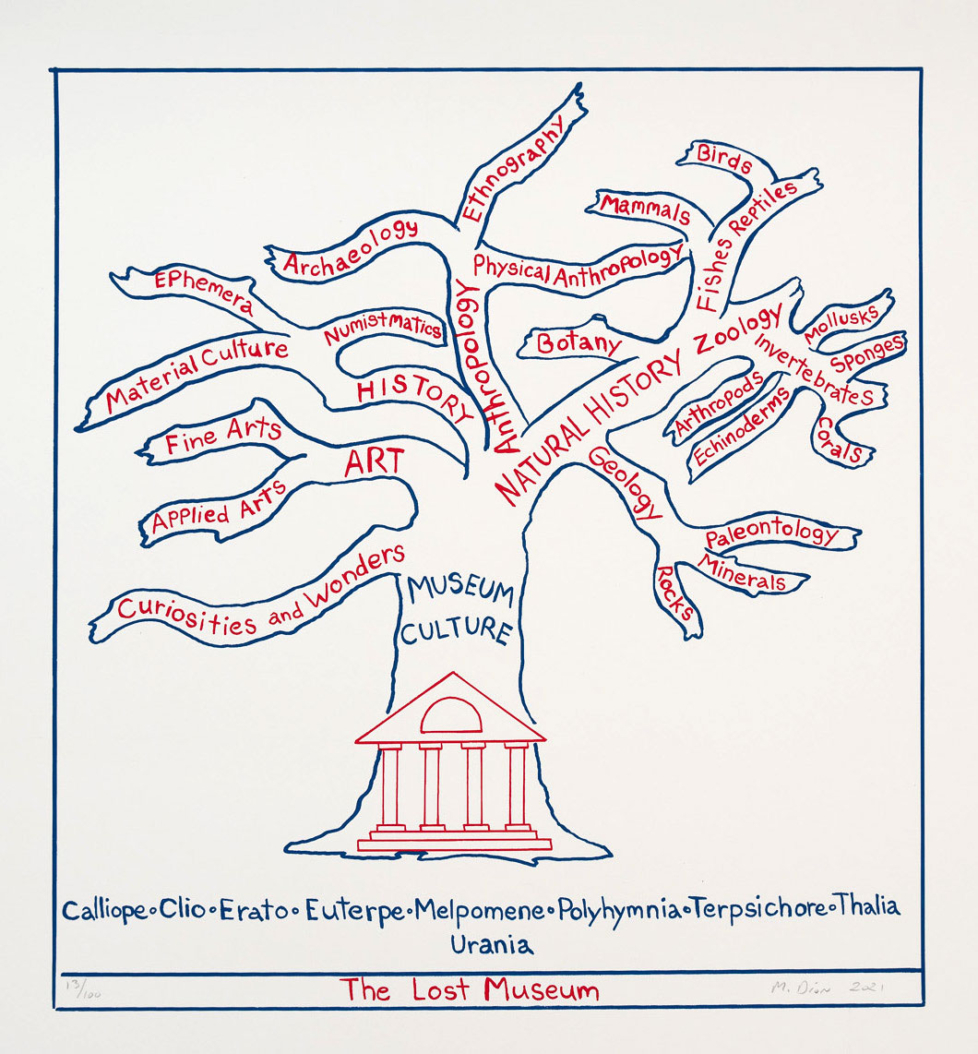

This spring hinted at a Malmö renaissance, marked by strong institutional programming, but the autumn feels more restrained. Malmö Konsthall shows artists with disabilities, stressing the power of visual language, Moderna Museet Malmö presents Edi Hila and Lee Mingwei, while Malmö Art Museum explores its own legacy as an encyclopaedic institution. Still, Malmö may surprise with filmmaker Amin Zouiten and Sámi activist Niilas Helander showcasing bold work at Skåne’s Konstförening and Signal, respectively.

Tactile, slow, and quietly defiant, textile art continues to shape contemporary art. Tensta Konsthall hosts the speculative group exhibition Soft Logic featuring, among others, Bella Rune, Luca Frei, and Damien Ajavon, while Sven-Harry’s Art Museum presents a sweeping history of woven work, from Märta Måås-Fjetterström and Barbro Nilsson to Andreas Eriksson and Pia Ferm. But we still lack a proper institutional retrospective of textile art’s historical roots. The Swedish National Museum has the collection. What is it waiting for?

Paging up and down has conditioned us to move quickly from crisis to image to outrage, and back again. Indeed, the most urgent question facing art institutions today isn’t necessarily what they show, but how they ask us to look. Among this season’s many exhibitions, the most compelling moments will be those that demand attention rather than assume it – works that slow us down, pull us in, and remind us that meaning doesn’t arrive instantly, but takes work.