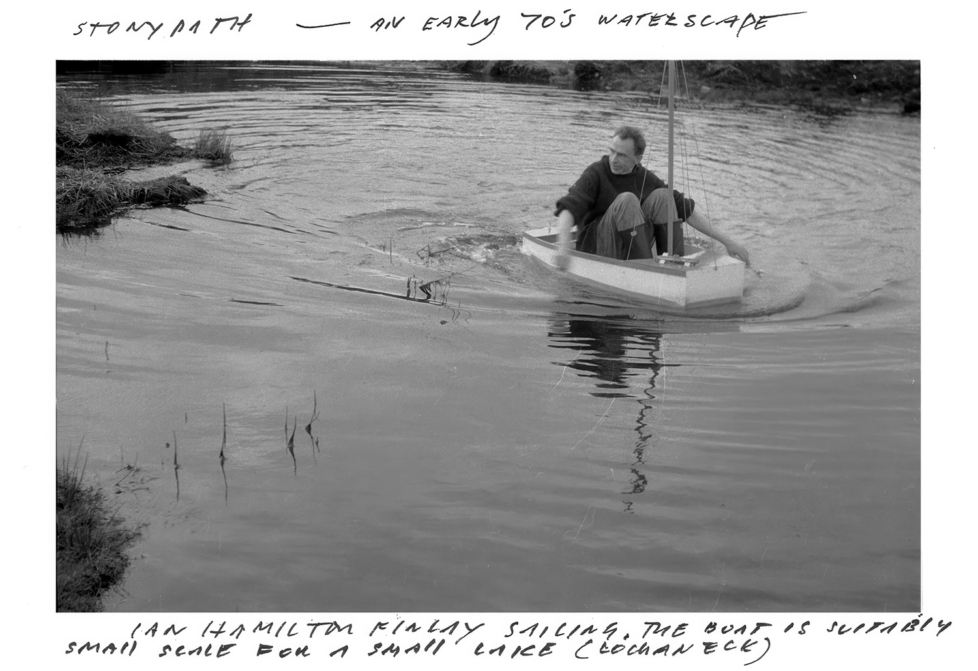

Portrait of Ian Hamilton Finlay in the lake at Stonypath/Little Sparta. Photo: The Estate of Ian Hamilton.

Together with a poet-friend, I travelled to Ian Hamilton Finlay’s (1925–2006) garden Little Sparta outside Edinburgh some fifteen years ago. It’s safe to say that we were astonished –both by the erudition behind the almost three hundred classically infused sculptures on display, as well as by the stubborn vision of the artist and his wife and collaborator, Sue Finlay. Together, they created the layout, which includes an artificial lake, across seven acres of Scottish farmland from the late 1960s and onwards.

Such pigheadedness was bound to provoke confrontation, and over the years Finlay became embroiled in several career-defining controversies. During a public commission in France in the 1980s, he faced accusations of fascist sympathies after using Nazi iconography in his work and making perceived anti-Semitic remarks in private correspondence. Finlay denied all allegations, yet the commission was cancelled, and the episode left a lasting mark on his reputation.

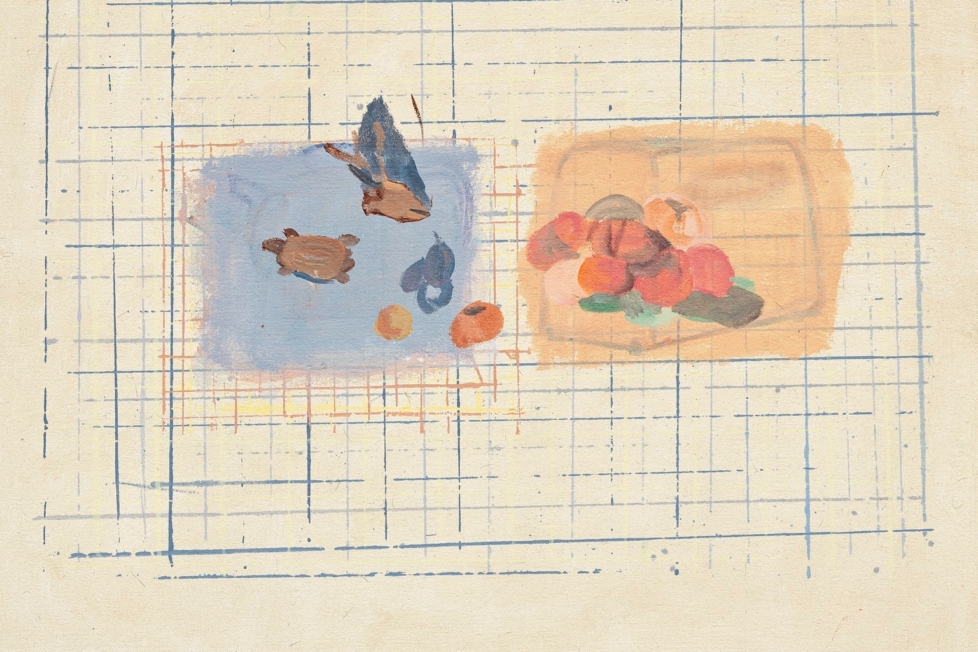

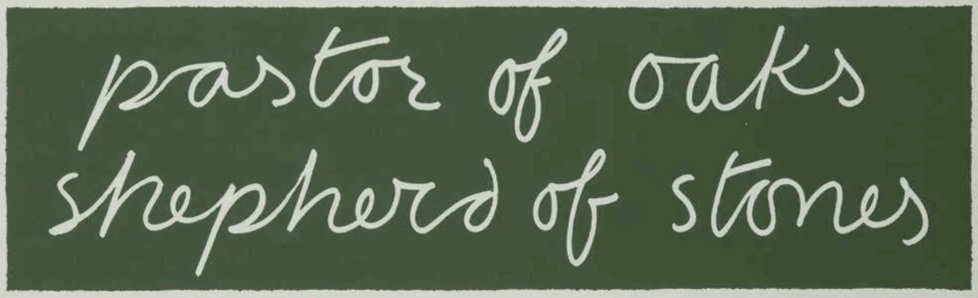

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Pastor of oaks / Shepherd of stones, 1992. In collaboration with Julie Farthing.

To mark Finlay’s centenary, a commemorative exhibition has been presented across eight international galleries, including Victoria Miro in London, Ingleby in Edinburgh, and David Nolan in New York. In a spiteful review of the London show, The Guardian’s critic Jonathan Jones – not finding any traces of Nazism in the works – instead focuses on the artist’s fascination with political violence and the French Revolution as proof that he was nothing more than a provocateur, an “idiot.” Jones frames his hatchet job as concerned with the lack of seriousness in Finlay’s work, yet it seems based on the assumption that political dissent can only ever be a provocation – never a legitimate position or a genuine intellectual concern.

This summer, the centenarian has also been presented at Marabouparken in Stockholm. Besides features in poetry journals like OEI and Tydningen (who made a thematic issue on Little Sparta a few years ago), this, to my knowledge, is the first presentation of Finlay to a Swedish audience. Rather than addressing his politics head-on, curator Erik Törnkvist’s introductory essay emphasises ambivalence and wit as integral to the work, stressing how it can be considered “both poetic and juvenile, humorous and melancholic, provocative and moralising, reactionary and revolutionary…”

The exhibition mainly focuses on Finlay’s mature period during the 1980s and 90s, and consists exclusively of works on paper. During my visit, I couldn’t help but wish that the presentation had included the artist’s sculptural work, and been allowed to expand throughout the entire kunsthalle and into the adjacent park. Yet, the low-key presentation has its merits, since Finlay’s dedication to printed matter allows his works to be distributed and displayed even with limited resources.

While Finlay shares certain traits with many Conceptual artists of his generation, his work has its roots in the Concrete Poetry movement of the 1950s and 60s, with its focus on the visual and material dimensions of language. For Finlay, this meant cutting the ties between poetry and literature in the traditional sense. Instead, he started to work with poetry in sculptural form, as well as with landscape design and prints that could be distributed by mail and shown in galleries and museums. Thus, the poet who began as an author turned into an artist, even though his work didn’t always align with the prevailing politics of the contemporary art world.

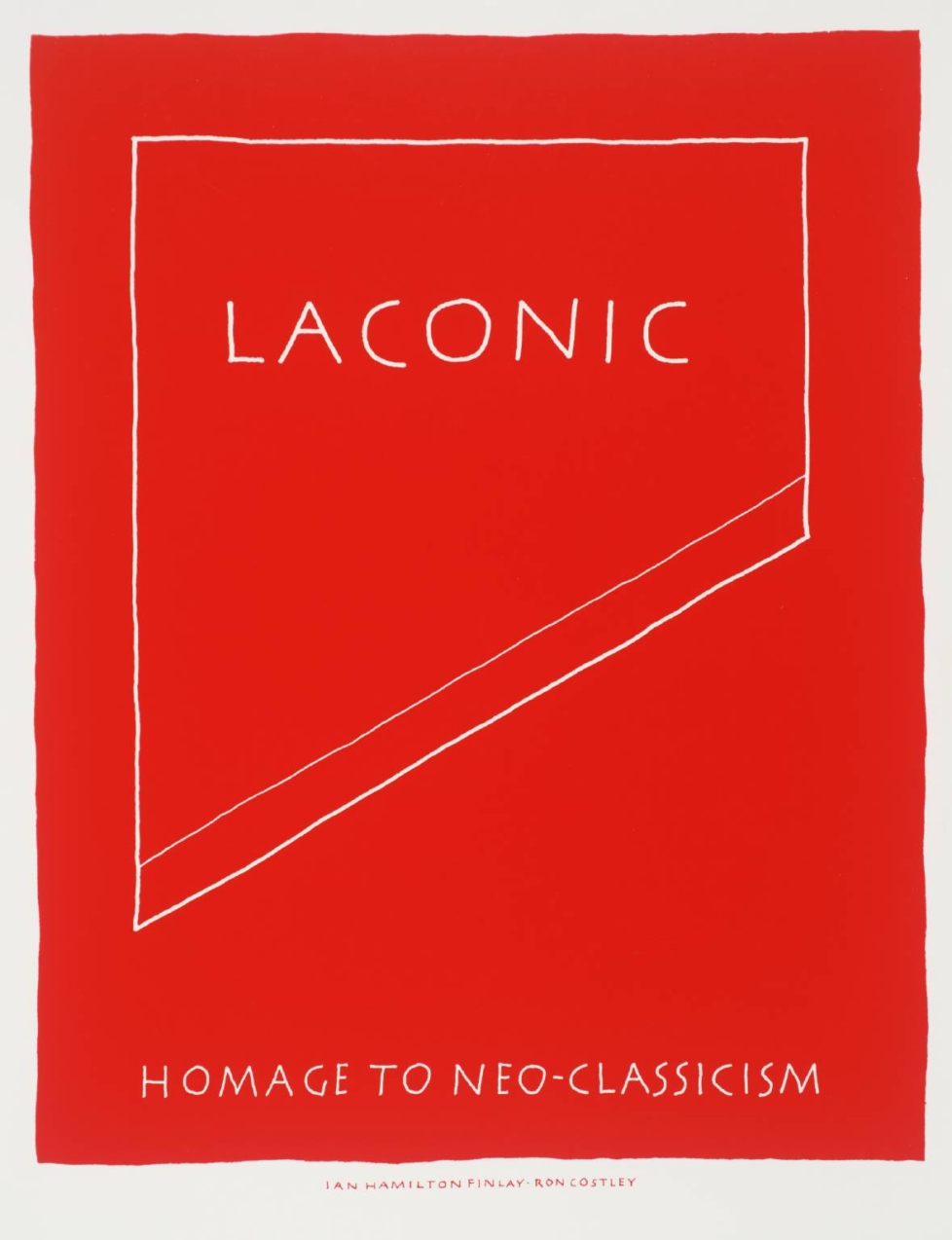

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Laconic, 1987. In collaboration with Ron Costley.

Although Finlay was reclusive and rarely travelled, he remained in close correspondence with fellow Concrete poets and artists of his time. Yet, he often comes across as less unequivocally modern than many of his peers. Perhaps he would have felt more at home during the Romantic era, when the classicism that he so loved wasn’t yet seen as politically suspicious?

To emphasise Finlay’s contradictory nature, Marabouparken’s exhibition highlights two opposing forces at play in his work: lyrical meditations on nature, on one hand, and revolutionary violence, on the other. In the centre of the room stand two posters depicting stylized guillotines with the inscriptions “laconic” and “the medium is the message.” Together with Ron Costley, Finlay created these works in 1987 as part of one of his many ‘wars’ – in this case, a dispute with the Strathclyde authorities who had challenged the fiscal status of one of the buildings at Little Sparta.

“Laconic” derives from Laconia, the homeland of the austere Spartans, and the name of Finlay’s garden was a pointed rebuke to the establishment of Edinburgh, known as the “Athens of the North.” The works may seem brutal, but they are also sophisticated, scholarly, and quite funny. Isn’t there, after all, a touch of self-irony in the artist’s theatrical defiance?

Two series placed around the guillotines dominate the room. First, what I – and surely many others – regard as some of Finlay’s most accomplished works, the poems Pastor of oaks / shepherd of stones (1992), Blue water’s bark (1992), and Dove, dead in its snows (1989), created together with the calligrapher Julie Farthing. The poems consist of the words in their titles, the watery theme subtly reinforced through typography and colour. At Marabouparken, they are arranged along a gently undulating horizon line that further emphasises the theme. Perhaps the Scottish provocateur’s gravest offence was his unapologetic devotion to beauty?

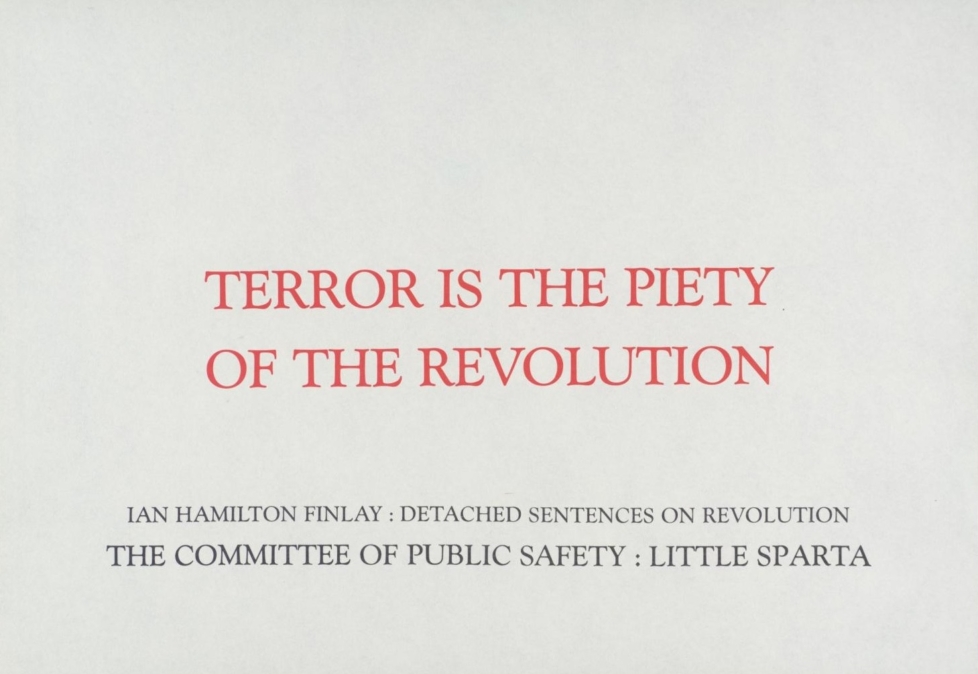

Also on display is the visually restrained Detached Sentences on Revolution (1980) in which aphorisms like “Terror is the piety / of the revolution” and “To be a hero / it is not enough / to write to bureaucracy twice” have been printed in red serif font on white paper. The work alludes to poet and landscape artist William Shenstone’s Unconnected Thoughts on Gardening (1764), which, among other things, compares a garden to an epic poem.

In Finlay’s hands, Shenstone’s notion of a poetic garden takes a political turn, echoing how Jacques Rancière frames both the French Revolution and the English garden as part of a broader “aesthetic revolution.” In his book The Time of the Landscape (2023), the French philosopher explains how, during the 18th century, a new mode of thought enabled statements or actions that defied social hierarchies which had previously been seen as natural. For instance, unlike the rigidly organised French parks, the new English gardens allowed visitors to wander freely as equals.

Indeed, if the aesthetic revolution liberated art from the social control of the ruling classes, then present-day critics, in The Guardian for instance, can be said to adhere to a counter-revolutionary mindset – one in in which acts of disobedience are dismissed and their authors ridiculed as fools.

To my mind, it would be more correct to describe Finlay as a committed classicist whose intellectual convictions were bound to clash with the modern world. In fact, wasn’t it a deeply classical pursuit of balance that compelled him to include the threat of violence in his work – not as an endorsement, as some would have it, but as an aesthetic and philosophical counterweight to the beauty, order, and harmony that he so ardently cultivated? For instance, the tranquil lake at Little Sparta is framed by an ominous black monolith reminiscent of the sail of a nuclear submarine.

As Marabouparken’s exhibition implies, the most important lesson of Finlay’s work might be its stubborn resistance to easy classification: it is neither a nostalgic retreat into the past nor a straightforward critique of the present, but rather a constant negotiation between the poetic and the political, the classical and the modern, the serene and the shocking. If critics today struggle with these contradictions, it may say less about the Scotsman and more about how contemporary culture demands clarity of allegiance and moral transparency, reading irony and provocation as dangerous obfuscations rather than as invitations to think more deeply.

Perhaps that is why, a hundred years after his birth, Finlay remains so difficult for some to reckon with. Yet to many, the dissonances and unresolved tensions are precisely what bear witness to the enduring complexity of his poetic imagination. With his grim inscriptions and blood-chilling guillotines, he offers a quiet but disruptive challenge: an art that marries lyricism and brutality, irony and sincerity, without ever allowing the viewer to fully relax into certainty. Indeed, to persevere with such a revolutionary spirit might, in the end, require a certain form of idiocy.