I find myself on the seventh floor of Pace’s palatial gallery complex in Chelsea. It is the opening of Robert Longo’s solo exhibition The Weight of Hope, and here, far above the main galleries, Rhys Chatham’s band G3 is performing. Its line-up consists of a group of gray-haired artists and musicians, including Longo himself. No fewer than five are playing electric guitars, one after another repeating the same short chords so that the noisy soundscape emerges as a sort of staggered, hypnotic feedback loop. Behind them, projected images show demonstrations and protests from around the world – a stream of crowds gathered to express their discontent with the status quo.

Every so often, the projection freezes momentarily on a single frame – for instance on Iranian women holding placards bearing the face of Mahsa Amini, a young woman arrested and murdered by the country’s morality police in 2022. Over and over, Trump’s contorted face appears, snarling into a microphone. It’s as if these old men – who grew up amid the American social upheavals and proxy wars of the 1960s and 70s, and punk’s subsequent nihilism – are reviving the countercultural aesthetics of their youth, now that the liberal world order seems to be unravelling. Meanwhile, the world beyond the gallery is treated as a mediated object, seemingly without impact on the space we’re in.

In New York, there are currently a number of exhibitions – including Longo’s – that directly or indirectly respond to the political turmoil of recent years: the storming of the Capitol, and the shock of another term under a more authoritarian Trump openly set on curtailing the rights of those with disabilities, trans people, sexual minorities, and women. The president has deployed the National Guard to several major cities, apparently because he believes it’s a good idea to train the military on his own population, while simultaneously throttling federal funding for everything from education to climate monitoring, as well as all kinds of measures meant to reduce social inequality. Amid all this, the news cycle has been punctured by a series of politically motivated assassination attempts. Meanwhile, it is striking how art is characterised by the same strategies that have defined the field for at least forty years: the appropriation of media imagery, neo-conceptualism’s decoding of power and control, and a nostalgic return to analogue media that contrasts with the fragmented digital present. While exhibition themes are updated in step with the zeitgeist, the methods and aesthetic imprints remain the same.

Everyone knows that the Trump administration is in the process of reinstalling the statues of Confederate generals that Black Lives Matter (BLM) protestors toppled in 2020, and is doing so while waging a deeply troubling campaign to reshape how American history is taught and narrated in universities and museums. Yet, the conversations I overhear at openings and galleries revolve around the fact that sales at the Armory Show were better than expected, and that the ongoing downturn in the art market, described in detail by Artnet among others, might therefore not be as drastic as feared. This is perhaps a natural consequence of the fact that the American art world is removed from public funding bodies and dependent on collectors and philanthropists. Paradoxically, this affords parts of the field – including many of New York’s important museums organised as private foundations – a certain degree of protection from the kind of direct political interference currently affecting federally funded institutions. Whether the respite that comes with private money will last, however, seems highly uncertain.

Longo’s monumental charcoal drawings are good examples of the aesthetic stagnation mentioned above. For the most part, these works are pathos-laden reproductions of press photographs from The New York Times: the American flag held upside down during a BLM protest, artillery fire in Ukraine, migrants at sea, ice floes melting in the Arctic. Undoubtedly, these drawings hold a certain power. But they also seem to present little more than a succession of political crises, without probing beneath the surface or offering any framework for understanding them. A monumental drawing featuring the murdered Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Untitled (Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi; Istanbul, Turkey; October 2, 2018) (2019), his striped face rendered almost unrecognisable due to the low-resolution video source, stands out as one of the more compelling works in the exhibition.

The anonymisation of Khashoggi connects to the fact that his murder quickly disappeared from the media, largely due to the stream of events that make up the rest of the exhibition. The choice of the journalist as subject also highlights the absence of other widely discussed current events: Israel’s systematic killing of journalists in Gaza using American-made weapons, for instance, goes unmentioned. In an interview with The Brooklyn Rail, Longo says that the images of the genocide are so horrific he cannot bring himself to engage with them. But does the violence really need to be depicted directly in order for it to be addressed? Perhaps this omission also indicates which subjects are deemed acceptable by New York’s collector and patron class. In Longo’s exhibition, the world is viewed from a vantage point shaped by American hegemony and the country’s liberal media. The fundamental problem is that the exhibition itself doesn’t reflect on this position.

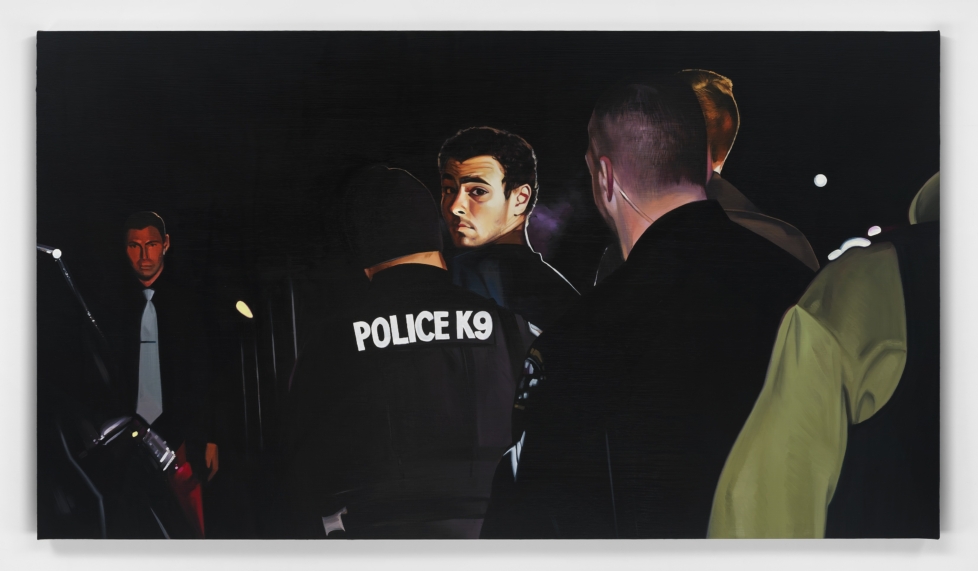

Sam McKinniss employs an appropriation-based strategy that seems to follow in Longo’s footsteps, albeit with a cheekier, more playful, and less self-serious attitude. His exhibition Law and Order at Jeffrey Deitch features paintings of figures portrayed in the media as either heroes or villains, alongside superheroes and their nemeses, as well as renderings of various sites associated with punishment. The iconic photograph of Luigi Mangione being led into the courtroom wearing a bulletproof vest is reproduced with a smooth and soulless quality in Luigi Mangione with Police Escort (2025), making him resemble a doll or marionette. Other subjects include a close-up of Batman and Catwoman from The Dark Knight Rises (2012) – Bruce Wayne and Selina Kyle (2025) – and a landscape painting of a notorious ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) detention camp in Florida, La Salle Detention Facility (2025).

Whereas the Pictures Generation, to which Longo belongs, was primarily concerned with problematising uncritical notions of originality and authenticity, McKinniss uses the same strategies to reveal how all kinds of narratives – from news reports and films to memes – now circulate with the same speed and intensity, thereby acquiring the same epistemological status. McKinniss operates in a context where images move between traditional and social media, and where narratives that touch on questions of right and wrong have become porous and hollowed out, made into memes or entertainment. His work addresses this breakdown of consensus reality – the condition we refer to as “post-truth” – through paintings that can be read as imprints of a prevailing relativism in which all stories are granted equal validity.

Scattered across Cady Noland’s untitled exhibition at Gagosian are empty Budweiser cans, spent and unspent shotgun shells, revolvers, and facsimiles of advertisements for ear protection used on shooting ranges. On the floor and various tables partly surrounded by barriers lie newspaper clippings about famous assassinations and assassins, many blown up to monumental scale. They bear the grainy aesthetic of the photocopy, as if pulled from an anonymous institutional archive. Like the books of the great American postmodern novelists Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo, Noland’s pieces are suffused with an uneasy fascination with paranoia, violence, and conspiracy. She gives form to DeLillo’s speculations in his novel MAO II (1991) about whether the terrorist has replaced the writer – and, by extension, the artist – as the one who shapes society’s consciousness. Is violence the most effective way to cut through the noise of mass media?

As always, Noland comes across as clinical and anti-aesthetic. The readymade aesthetic that she began shaping in the 1990s feels closer to reality today than ever before, even though it has changed little over the years. It bears all the classic hallmarks of American neo-conceptualism: a critical dissection of mass culture – advertising, consumer goods, architecture – that zeroes in on how these seemingly banal forms carry traces of power, control, latent aggression, and systemic dysfunction. A key part of the mythology around the notoriously reclusive Noland is that she supposedly threatened to shoot Larry Gagosian should he attempt to do an exhibition with her, adding that Gagosian is where artists go to die. The fact that this exhibition takes place at Gagosian in itself indicates that the strategies mentioned above have now been emptied of their critical potential. Instead, the works risk merely reflecting a reality where violence is already palpable; they no longer dig into a collective unconscious where it lies latent.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas’s installation Peace Core (2024), a rotating sphere covered in screens, is on view at another Gagosian branch and serves as a reminder of how good we, the citizens of the so-called West, had it during the period of stability and economic growth from the late 1980s to 2000. The work features television footage from 11 September 2001– the day that marked the threshold to the catastrophic “War on Terror” – interspersed with clips of mindless reality TV, stock market advice, adverts for breakfast cereal, and music videos, all edited together so that new patterns continually emerge across the screens. Here, American media hegemony appears as a machine that once produced a single reality that all of society was plugged into. While liberal forces in American public life have long clung on to the remnants of this consensus reality, MAGA strategists have systematically constructed counter-narratives about everything from Obama’s birth certificate and vaccines to the Democratic Party elite. The notion that we once lived in a coherent reality, consuming the same images of the world as everyone else, now seems rather unbelievable.

The image on the cover of the latest issue of Civilization, a newspaper-format journal founded by Richard Turley and Lucas Mascatello, is equally telling: it depicts a kind of MS Paint caricature of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920) on fire. The magazine’s launch in mid-September was held at Kulendran Thomas’s project space Earth, which is located in a stripped-down storefront. There, attendees were invited to read aloud from the paper on stage. Behind them, a video projection appeared to function as subtitles. But, as Kulendran Thomas explained, this projection was in fact an algorithm continuously attempting to predict the reader’s next word in real time. The algorithm updated its predictions constantly, producing a kind of feverish, unintelligible glossolalia. The format exposed the underlying logic of predictive technology: that all human activity, including language use, can in principle be anticipated and modelled. In line with some of Kulendran’s AI-based works, it also raised the question of whether aesthetic innovation is possible at all when so much of both machine and human culture is built on the recombination of already existing material.

Other artists take more personal and direct approaches. Erin M. Riley’s tapestries at PPOW assemble images and videos from her upbringing into narrative collages. In his solo exhibition at the artist-run gallery CANADA, Kahlil Robert Irving presents a monumental screen print composed of fragments of emails and visual material from his digital archive, addressing the African American experience in relation to today’s media landscape. One witty detail is a text fragment where Irving notes that the rap group Outkast lasted longer than the Confederacy, and that their impact on American culture is therefore greater. Hence, he argues, statues of Confederate generals should be torn down and replaced with ones of Outkast. This is one of the few works I’ve seen during my weeks in New York that engages with the country’s political turmoil through a personal statement rather than analytical detachment.

In the 20th century, significant aesthetic upheavals occurred in art when artists realised that their existing strategies were out of step with the spirit of times. This was the case when the Futurists attempted to pulverise the past through their celebration of war and acceleration; when the Surrealists developed their ambition to liberate the unconscious and summon revolution; and when Dadaism nihilistically rejected meaning and reason. The American art historian Hal Foster observes that Trump’s perennial denial of reality recalls the absurdist strategies of Dadaism. Perhaps, today, it has become difficult to imagine the world otherwise precisely because the speculative and the absurd are now the preferred tactics of authoritarian leaders. We have become accustomed to Trump and other political figures of similar persuasion denying their own statements and rewriting events as it suits them in the moment. In doing so, the authoritarians have taken over art’s traditional privilege, that of being speculative and irrational. Such strategies now appear suspect, perhaps even dangerous – not because they have become political tools (they always were), but because they have been appropriated by authoritarian forces. The tragedy for art, then, is that it is left with a reduced field of possibility.

Foster has also written about how the leading American art critics of the 1960s and 70s, such as Michael Fried, imagined that art could be in a state of perpetual change, and thus compensate for the political revolution that never came. This belief in art as a substitute for politics now seems, as Foster points out, rather far-fetched and more than a little naïve. Yet, when deprived of a credible political or social function, art risks being reduced to a commodity, capable of nothing more than recycling contemporary events as pure surface. For the mechanisms of recombination and appropriation shape not only art, but the whole of contemporary American political and social reality. In a country where the authorities’ account of reality is pure fiction, art, for the time being, seems unable to imagine anything beyond what already exists.

Translated from Norwegian