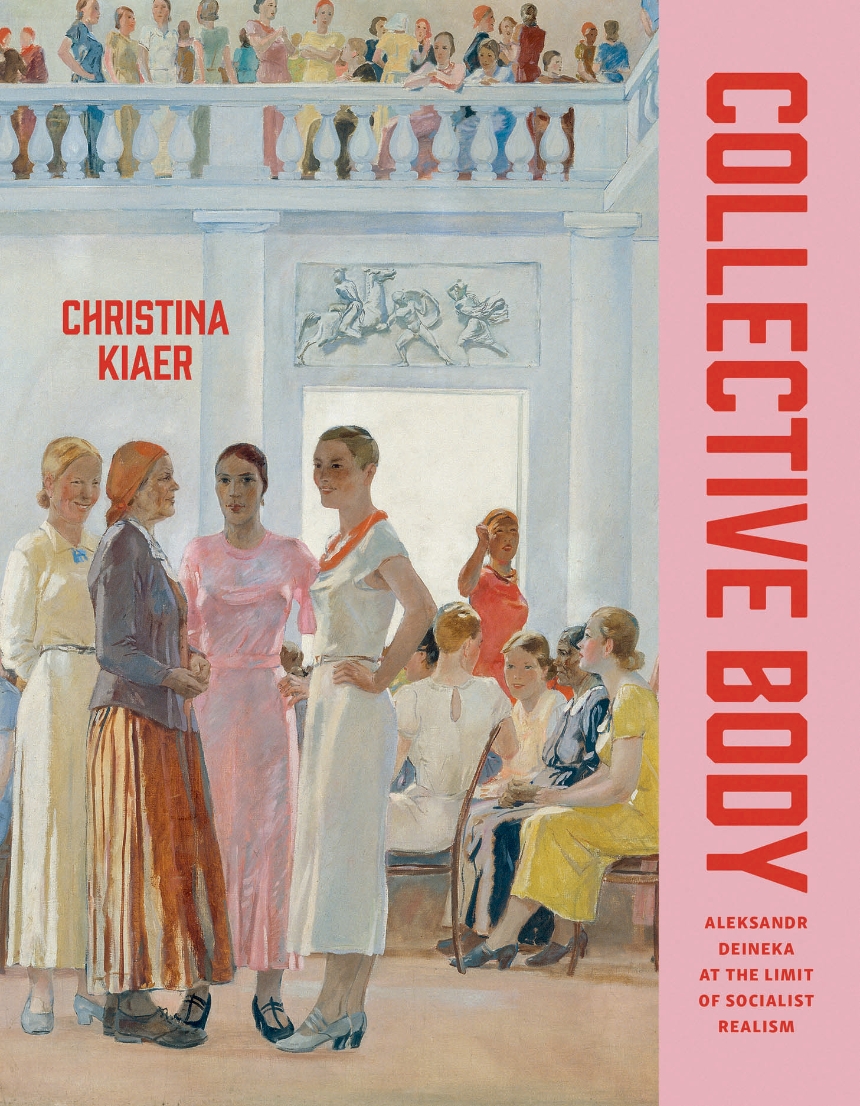

“It will be an unusually personal talk,” the Danish-American art historian Christina Kiaer, who will deliver this year’s FORART lecture at Litteraturhuset in Oslo this coming Friday, told Kunstkritikk. When Kiaer published her most recent book on the Soviet painter Alexandr Deineka (1899–1969) last year, she realised that her academic career had unfolded within a thirty-year window from the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991 to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

“I am going to be sharing when I first went to the Soviet Union to do research in 1992, what kinds of possibilities there were, as the country almost immediately opened everything up and was entering into this period of aspirational liberal democracy,” Kiaer said on the phone from Chicago, where she is Frances Hooper Professor of Art and Humanities and Chair of the Department of Art History at Northwestern University.

As the years went by and Putin came to power, Kiaer found that it became gradually more complicated to conduct research and collaborate with Russian museums. And after the full-scale invasion, it has become almost impossible. Earlier this year, Russia declared the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES), of which Kiaer is a member, to be a “threat to the foundations of the constitutional order of Russia.” Membership can be punished with forced labour or imprisonment, and the ban has made it difficult for American, British, and European researchers to do their work.

In her lecture, Kiaer will discuss how her research interests over the years have shifted from the Russian avant-garde to Socialist Realism, which she sees in the context of broader historical shifts. When Russia emerged from the Soviet Union, it wanted to distance itself from Socialist Realism and export the avant-garde in order to appear liberal. But as the country moved toward a more authoritarian form of democracy, Socialist Realism once again rose to prominence – this time with a nationalist purpose. “In retrospect, I understand that I was contributing to this shift, even if the interest I had came from an interest in Socialist Realism as a communist art system and what that meant,” Kiaer said.

Kiaer has been invited to Oslo by FORART (Institute for Research within International Contemporary Art), a foundation dedicated to contemporary art-historical research, to share her knowledge of Soviet art history under Putin. Ina Blom, board member of FORART and professor of art history at the University of Oslo, said that Kiaer’s research is compelling for many reasons. Her work in the Soviet archives has, among other things, resulted in some of the most original analyses of Russian Constructivism that Blom has read. “She shows how these artists, under the pressure of Lenin’s temporary turn toward a market economy in the years after 1921, developed a distinctly socialist definition of the Western concept of the commodity,” Blom said. According to Blom, this altered the prevailing art-historical understanding of their work and sharply distinguished it from the Western European avant-garde.

Kiaer thinks that there is much in the Soviet art system that remains relevant for us to think about today. In particular, that it was state-funded and collectively run by artists and critics themselves. A few were party members and tried to steer things in certain directions, but it was a large group of people who debated “establishing systems where there was basically full employment for artists, artists had places to live, and studios; people were being paid to make things and to go on trips to see the construction of new aspects of the whole industrialisation project and make images and films of it.”

Kiaer believes there are things to admire in this collective system, which stands in radical contrast to the market-driven art of the West. “I have claimed that individual artists found ways to function within those mechanisms that allowed them to develop their own voice, even though their voice was still part of a collective project,” she said.

Blom also highlights this aspect of Kiaer’s research: “More recently, she has taken a new look at Socialist Realism under Stalin and examined what ideals and expressive possibilities could exist within a genre that very few have wanted to engage with.”

However, living in a United States that is becoming what Kiaer called a “nascent authoritarian state” has affected her view of her earlier work. She now sees that she has argued from a privileged position, as someone who has never personally experienced restrictions on her own freedom of speech. She observes that American universities have begun entering into agreements with President Donald Trump, who requires faculties to submit their syllabi to an external body for approval before they can teach, “which is the very beginning of the kinds of authoritarian attempts to constrain knowledge and knowledge production that we saw in the Soviet Union.”

In addition to discussing what is happening in Russia now with censorship, canceled exhibitions, and the withdrawal of funding, Kiaer’s lecture will also address some of Trump’s decrees and executive orders, how universities are under pressure, as well as the president’s criticism of American museums for harboring inappropriate ideologies, which she remarked “was precisely a Soviet idea, right?”

Kiaer still believes socialism is a good idea, and that the collective project of the artists she has studied was important. But experiencing her own freedom of expression under threat has made her skeptical of any form of enforced collectivity, “since the same mechanisms can so easily be used for more frightening purposes.” Kiaer thinks it is pertinent that we find ways and venues for artists to be able to make and exhibit their work and be critical, adding: “and as scholars, we just have to continue asserting our first amendment rights to say whatever we want.”

The FORART lecture takes place Friday, 5 September, from 18:00 – 20:00 at Litteraturhuset in Oslo.