A retrospective can become the kiss of death for an artist’s career. Narratives become fixed, aesthetics embalmed, and later works risk looking like tired rehashes when shown alongside older key works. Marie-Louise Ekman’s major retrospective at Moderna Museet in 2017 avoided this thanks to its broad selection: paintings, prints, textile works, glass sculptures, vitrines, films, furniture, and murals.

The fact that Ekman, in addition to being a visual artist, has worked in theatre, television, film, and radio came across as an artistic strategy for constantly shifting and transforming themes running through her practice: the subversion of normality and the quotidian; the role of the artist; dysfunctional family relationships; gender transgressions.

At the age of 80, Ekman is currently showing new works at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm. She appears more determined than ever – and definitely more grandiose. For the first time, she has worked on a significantly larger scale. Her naïve style which has always drawn so much of its energy from humour, now feels desolate.

The four-metre-high Chandelier (2025) sits alone in the middle of one of the spacious galleries, where it glitters childishly against the flesh-pink floor. The fixture’s white glass tubes extend far into the room, and the ends are crowned with figures from her absurd psychodramas. However, when the dog, the bed, the bubble fart, and the others are assigned roles as light sources in an interior design object, they merely signal a style; all subversive ambitions have been obliterated. The piece would be perfect in the foyer of an opera house. Yes, it’s grandiose.

Covering a long wall in the adjacent gallery, a gigantic mural depicts an empty room in one-point perspective with four doors that don’t lead anywhere. It’s classic Ekman, whose ambiguous interiors are offered as projection surfaces. Home? Stage? Studio? Hospital? All at once, of course. On the floor below, a jumble of iconic photographs show Ekman as a young woman in the 60s and 70s. Yet, the fact that visitors can’t avoid stepping on the archival black and white prints mercifully defuses any reverence for the 68-movement so often idealised among the contemporary art crowd.

Loneliness has long been a recurring theme in Ekman’s paintings. While her work in theatre and film has been a way for her to assemble groups around playful ideas, her paintings have rarely depicted collective processes or communities. While a feature film such as The Elephant Walk (Barnförbjudet, 1979) and the television series The Art School(Målarskolan, 1990) toy with gender roles and narrative perspectives, the characters in her paintings remain solitary. Renderings of empty walls and facades reinforce the feeling of isolation. In several of the new works, this is more noticeable and intense.

Man, Pencil and Line (2023) depict a headless male body against a light green background. Reddish-pink flesh glows from his neck. A giant yellow pencil wraps around the body, drawing a razor-sharp line in the air. It is a simple image – clean and full of monochrome surfaces. In other paintings, a blonde woman in a red dress is set against a light brown background. In Woman and Body Parts (2024), she stands with her back to us, looking at shelves of cracked torsos and heads. Has her loneliness become more severe?

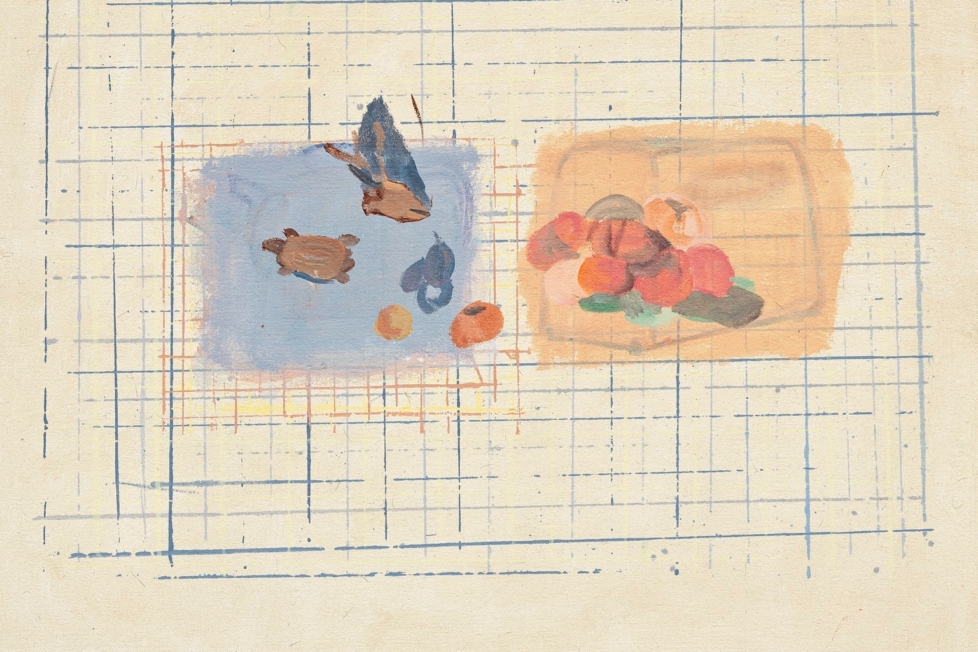

In the smallest gallery, Ekman’s studio has merged with the room. On simple folding tables, she has placed documents, sketches, and photographs alongside knickknacks, paint cans, and paraphernalia. It seems positive for her to demystify herself in this way. She is obviously doing some well needed death cleaning. Ekman has also made sloppy drawings and scribbled directly on the floor. On a roll of canvas in the middle of the room, she has worked on some sort of spontaneous collage. She seems to have just kept on going, right up to the end of the installation process.

The paintings in this room also contain more material, and it is difficult to decipher all the traces. But you’re not meant to understand everything here. The revelling in hospital colours probably has its reasons. But bodies without heads, faces without eyes, shoes without legs? I imagine it is often very straightforward for her: “This is how I feel right now!”

At Konstakademien, Ekman seems to establish a ‘late style’. The larger formats reveal a new kind of sincerity, while experiences that were previously masked behind absurdism and contradictions now appear completely rational. In the painting Woman in a Green Dress (2025), a woman lies bleeding profusely from her neck. She is encircled by what appear to be elements from her life: a crying sausage, a silent mouth, a knife that wants to cut. This is what a monumental end to a life in the service of art and madness looks like.