When I was at university during the so-called ‘reconstruction’ of the Soviet Union, the perestroika of the late 1980s, Russian was considered the language of a brighter future. Therefore I chose it as one of my subjects. That future never happened, but I have never regretted my choice. Thanks to these Russian skills, I have been able to study phenomena such as ethno-futurism in Russia’s Fenno-Ugric republics, Georgian 1920s modernism, or the Central Asian contemporary art scene.

I have allowed myself to be guided by the principle that anyone wanting to understand the Russian Empire in its historical and present incarnations would do well to talk to its non-Russian subjects. In the almost thirty-five years since the collapse of the USSR, a decolonial mentality has begun to emerge throughout what used to be Russia’s dominions, slower and more tentatively than in other colonised parts of the world. Trying to grasp this process and making it graspable to audiences in Western or Northern Europe has been a significant aspect of my activities as an exhibition-maker and writer.

I was recently in Kazakhstan, the world’s largest land-locked country, squeezed between Russia and China. The reason for this visit, my fourth, was the inauguration of two new cultural institutions in its largest city, Almaty: an experimental cultural centre in a purposely reconstructed 61-year-old flagship cinema theatre; and a proudly mainstream museum of modern and contemporary art built from a personal collection of mostly Kazakhstani painting, sculpture, and works on paper.

The colonised subject – as a psychological reality or a mental image – continues to haunt the narrative that now cloaks decades of daring and resilience by artists, curators, and scholars in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Namely, that this region is suddenly the art world’s next new thing. In Uzbekistan, the government invests heavily in the Bukhara Biennial, the Center for Contemporary Art Tashkent (both recently inaugurated), the country’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale, and other initiatives, while in Kazakhstan private actors dominate the contemporary art scene. Turkmenistan, the fifth of the post-Soviet ‘stans’, remains supremely impenetrable to artistic freedom and its alien blessings.

Alma, a new museum squeezed between Moscow and Beijing

“I’m doing Central Asia,” an American academic in bubble-gum pink Balenciaga intimated during one of the receptions that kicked off Alma, the Almaty Museum of Arts. I was invited to Kazakhstan’s commercial and cultural capital to join the opening programme for the Tselinny Centre of Contemporary Culture, but let me first relate some of my impressions of the new museum, which opened the same week in September after four years of construction, with the collection storage facilities still not quite finished.

Commissioned by the art collector Nurlan Smagulov, who has made his fortune by assembling and selling cars (destined for the Kazakhstani and Russian markets) and on building and running large shopping malls, the building was designed by Chris Lanksbury of the British architecture firm Chapman Taylor, known for its shopping malls all over the world – from Almaty (three of them, all owned by Mr. Smagulov), Baku, and Charleroi to Urumqi, Warsaw, and Wuppertal.

Before entering the museum, visitors can admire samples of quintessential middlebrow plop art by Alicja Kwade, Jaume Plensa, and Yinka Shonibare. Inside the main nave, they will be struck by the different claddings signalling the different durations of temporary exhibitions (brushed aluminium to the left) and the permanent “artist rooms” with works by Richard Serra, Anselm Kiefer, Bill Viola, and Yayoi Kusama, and the semi-permanent display of the founder’s Central Asian collection (polished limestone to the right). Both these materials, which also appear on the outdoor façades, are offset with generous detailing in rusty steel.

The press group that I belonged to was met in this lobby by Mr. Smagulov and the museum’s artistic director Meruyert Kalieva, who is also the owner and director of Aspan Gallery in Almaty. I also got a chance to talk to the museum’s Latvian chief curator Inga Lāce, responsible for the collection hang, as well as with Almagul Menlibaeva, the Berlin- and Almaty-based Kazakh artist featured in the museum’s inaugural retrospective solo exhibition I Understand Everything, and with the exhibition’s Bangkok-based curator Gridthiya Gaweewong.

Menlibaeva – whom I know from my work at M HKA in Antwerp, which holds a collection of Central Asian contemporary art – told me that one reason she had asked for a collaboration with Gaweewong was to remind audiences that Kazakhstan belongs to a wider Asian art scene. Her geopolitical argument is less self-evident than it might appear. It is strategically astute and by no means innocent, much like her feminist and ecologically themed video art of recent years. If Kazakhstan is to be seen as Asian, which really means identifying with continent dominated by Beijing, can it still also be counted as post-Soviet, which really means being stuck in an orbit centred on Moscow?

To the imperial mind – and some such minds, whether fully self-aware or not, were in evidence during this week of opening festivities – the subjugated or colonised subject (the “subaltern” that we might recognise from Gayatri Spivak’s writing) lacks the sophistication to make such judgments about its own position and trajectory, and therefore also the wherewithal to independently convert them into free action. To a representative of the erstwhile centre, if the eternal periphery wants to reorient itself it must simply be misguided – which really means guided by some other competing centre

Yes, the subaltern might very well be able to build a museum if he is a self-made almost-billionaire, but he will be mercilessly judged for it. It is too ostentatious, looks too much like a shopping mall or a convention centre, features too many contradictory diagonals falling over each other at awkward angles. Against this, it might be argued that a stroll through a sinuous corten steel labyrinth or a one-minute infinity room session is what it takes to attract enough of the 2.3 million inhabitants of a city that never had this kind of museum. Then the temporary exhibitions and the public events, and possibly the publications, can do the job of shaping these first-time visitors into a discerning audience. Like with every other private museum, its future will depend on the owner’s continued commitment to paying for the learning curve. But I can still understand the satisfaction of my Almaty art world colleagues who have been waiting thirty years for something like this to happen.

Tselinny, from Soviet cinema theatre to experimental cultural centre

A distinct alternative is offered by another Kazakh oligarch, Kairat Boranbayev. He is best known for owning the football club Kairat Almaty (now in the Champions’ League), for being imprisoned on charges of embezzlement in relation to gas sales in the aftermath of Kazakhstan’s opaque January 2022 upheaval, and for being released one and a half years later. A charismatic, youthful man with a disarming sense of humour, Mr. Boranbayev would most probably never be seen wearing a panama hat and a hand-knotted bow tie, the attire Mr. Smagulov chose for receiving the first visitors to his museum.

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture weaves together two strands of interdisciplinary programming: on the one hand performances and visual displays in its newly re-inaugurated building, on the other hand research, publishing, and learning in both physical and digital space. The centre is directed by Jamilya Nurkalieva, who previously managed the Art and Education Programme for the world’s fair EXPO-2017 in Kazakhstan’s capital Astana. Mr. Boranbayev’s daughter Alima Kairat, educated at the Courtauld Institute and Goldsmiths’ College in London, is the artistic director. Tselinny, taking pride in flat hierarchies, also employs an array of young creatives from the Almaty arts scene, the largest and most diverse in Central Asia. One of them is the poet and editor Anuar Duisenbinov, whom I spoke to at some length after returning to Helsinki, where I live. I will get back to him in a moment.

In its twists and turns, the story of Tselinny is illustrative of how Kazakhstan is seeking to position itself in the wider world – not just that of contemporary art and culture – after Russia’s attack on Ukraine in late February 2022. We should remember that the so-called “full-scale invasion” happened soon after the so-called “unrest” in Kazakhstan in early January. What began as a protest against an increase in petrol prices may or may not have morphed into an attempted coup, but it did lead to a state of emergency, the death of some two hundred people, looting in Almaty, the demotion of the previous president Nazarbayev, the consolidation of the power of the current president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, and a week-long peace-keeping intervention by Russia and other former Soviet republics.

The stark income inequality of Kazakhstan’s extraction-based economy is seen as an underlying reason for these events. Although the predominant mode of addressing them seems to be disinterested confusion, the largest square in Almaty is being beautified with a grid of fountains just in case, making it harder to rally crowds there.

Put simply, in the fourth year of what was supposed to be a ’small victorious war’ lasting a few days or at most a couple of weeks, Kazakhstan is still very tied up with Russia. But if Russia were to actively destabilise Kazakhstan, it would risk antagonising China, on which it has, in the meantime, made itself almost abjectly dependent. Since the early 1990s, Kazakhstan has also played a few Western cards, notably the US, the EU, and Japan, and it is no coincidence that much of the construction in Almaty and Astana is done by Turkish companies.

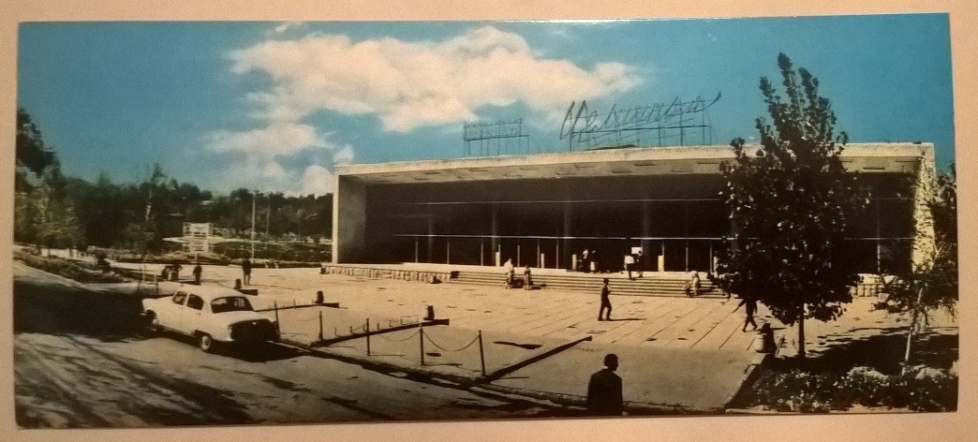

Cinema was one of the main instruments of propaganda in the USSR. Tselinny is an adjective formed from the Russian noun tselina, which is usually translated as “virgin land,” but is, in turn, derived from an adjective meaning “whole” or “untouched.” The post-Stalinist project of shock-and-awe land colonisation for wheat monoculture in southern Siberia and northern Kazakhstan, launched by Nikita Khrushchev in 1953–54, carried this name. So did the cinema theatre in Almay built to mark the tenth anniversary of the campaign – and to block the façade of the Russian Orthodox St. Nicholas Cathedral just behind it, adding the benefit of visually promoting atheism.

The Virgin Lands programme initially yielded impressive harvests, but very soon depleted the already dry and saline soils. The ecological mismanagement was exacerbated by the diversion, in the 1960s, of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for industrial-scale cotton production in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, causing the near-death of the Aral Sea, once the world’s fourth-largest lake, and leaving behind a salt desert. On top of all this environmental damage, the USSR used the territory of Kazakhstan for testing nuclear bombs and launching spaceships. Alima Kairat says she is not surprised when Kazakh intellectuals point out to her that the continued use of the name Tselinny “makes our ears bleed.”

Russian and Soviet colonisation of the Central Asian steppes, which for millennia had seen waves of nomads rolling in, has had dire consequences for the region’s Turkic-speaking population. After a century of trying to balance between the Romanov and Qing dynasties, the Kazakh Khanate finally succumbed to the former in 1848. Soviet power meant repression (here like everywhere else) and famine, during the civil war in the early 1920s and during the forced collectivisation of livestock in the early 1930s. Kazakhstan, which became a separate Soviet Republic in 1936, had eleven concentration camps and had to receive many of the peoples expelled from their home territories during the Second World War (among them the Volga Germans, the Crimean Tatars, and the Chechens). In official parlance, Kazakhstan became “a laboratory for the friendship of nations.”

Success is the best revenge – and also the best decolonial strategy, it might be argued. Business acumen and diplomatic adroitness are necessary when you want to transform yourself from subaltern (which, in Kazakhstan means speechlessness in standardised Russian) into subject (which everywhere means unlearning helplessness). The story of the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture begins in 2016 when Mr. Boranbayev bought the run-down former cinema theatre. At the time – when Russia had already annexed Crimea, but the whole world decided to accept it because no shots had been fired – the most interesting and important thing appeared to be the one closest at hand: the building itself as a clue to the history of Soviet international-style and Brutalist architecture, with its carefully calibrated concessions to nationalist form in the struggle for socialist content.

So the best person to approach for advice and assistance was the young director of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, Anton Belov, well known for his interest in the modernist heritage of the USSR. It helped that Mr. Boranbayev was already involved as a patron for this institution founded by the famous oligarch Roman Abramovich in 2008. ‘The Beginning’, the first project at Tselinny in its new reincarnation focused precisely on researching and preserving the post-Stalinist Soviet architectural heritage of Almaty. It yielded, among other things, the book Alma-Ata: A Guide to Soviet Modernist Architecture 1955–1991, published by Garage with support from Tselinny in 2018. The city was known as Alma-Ata (Father of the Apples) in the USSR and as Verny (The Loyal One) in the Russian Empire. What’s in a name? In a book title? Surely just a light-hearted reference to a shared cultural heritage, and besides, doesn’t it reflect a historical truth that no art-washing can ever bleach out?

In a short speech during the opening days, Mr. Boranbayev acknowledged Mr. Belov’s role in rediscovering, behind an early-naughties drywall in the front lobby, some orientalist decorative sgraffito panels by the Almaty-based Russian printmaker and illustrator Evgeny Sidorkin (1930–82). The surviving fragments of these fairly typical examples of late-Khrushchev-era applied art have now been painstakingly conserved. I find them interesting as visual evidence of the journey that the building and the institution have been through, but not in themselves compelling or important. In my judgment, run-of-the mill Socialist Realism – following the recipe “nationalist in form, socialist in content” – should not be granted heritage status by default.

Before ‘The Beginning’ there was, in fact, another beginning in 2017, when British architect Asif Khan was invited to re-envisage Tselinny. The project is a collaboration between him and his wife, Kazakh architect Zaure Aitayeva, and the Almaty office NAAW. It has resulted in an airy sequenceof lobbies, semi-separated from the gently raised outdoor square by an undulating wall of thin white steel lamellae and leading into a tall and multi-functional grey box where 1,536 cinema-goers would once have been seated in raised rows. The adaptability of such spaces is in theory endless. In practice, their preparation for, say, exhibitions of wall-hung artworks requires considerable effort and costs serious money. My overall impression of this building by Khan, who in his visualisations and his public appearances comes across as a believer in architecture as grand metaphor or pregnant image, was one of chalky and creamy whiteness with a sense of promise.

In the outer lobby, the exhibition From Sky to Earth: Tselinny by Asif Khan and How It Is Made was laid out under glass on a large round white table. Curated by Finnish architecture historian Markus Lähteenmäki, whose prime current specialisation is the architectures of Russian imperialism, the round-table display of photographs, texts, press cuttings, and other archival material was accompanied by an essay with the same title, in which Lähteenmäki lays out the facts behind Khan’s work and shadows Boris Eikhenbaum’s structuralist essay ‘Kak sdelana Shinel’ Gogolya’ (How Gogol’s Overcoat Is Made) from 1919. A series of models titled Lesser Known Scenes from the Recent Life of Tselinny, made under the supervision of Vassily Mikhailov, illustrated the chain of events that allowed the “desecrated” cinema – at some point it was a nightclub – to be resurrected as a respectable secular temple. Lähteenmäki’s intervention also helped capture the decolonial overtones of Khan’s and Aitayeva’s design.

Yet another new beginning for Tselinny, after the initial collaboration with Garage, was the appointment of an international advisory board in 2021. Contrary to what imperially oriented critic voices would have us believe, these experts – the curators Bart De Baere, Natasha Ginwala, and Martha Kirszenbaum, the sociologist Diana Kudaibergen and the artist Payam Sharifi (one half of Slavs and Tatars) – don’t embody the Anglo-Saxon discourse of decoloniality or a sharp turn towards Occidentalist internationalism. They stand, rather, for long-time engagement with post-Soviet visual culture and in-depth experience of global exhibition practices.

Barsakelmes, a decolonial rock opera

If Tselinny has become associated with academic decolonial theory it is mostly because of the US-educated Circassian-Uzbek scholar Madina Lostan (also known under her Russified surname Tlostanova), professor of postcolonial feminism at Linköping University in Sweden. In 2020, Tselinny’s own publishing programme started with a Russian-language collection of her essays, whose title translates to “Decoloniality of Being, Knowledge and Perception.”

I had a longer conversation with Tlostanova as we were waiting for the interdisciplinary evening performance Barsakelmes (2025) to begin in what used to be the cinema auditorium. The towering felt sculpture Bosağa–Transition (2025) by Berlin-based Kazakh artist Gulnur Mukazhanova was already installed in the darkened space. Using traditional felting techniques and fine merino wool dyed in glowing primary colours, Mukazhanova addresses both the nomadic roots of Central Asian material culture and the spiritual yearnings of high modernist Western painting. As the title of her work suggests, it doubles as part of the set design for an unapologetically time- and space-consuming Gesamtkunstwerk envisioned and directed by Kazakh artist and musician SAMRATTAMA (Samrat Irzhazov) and brought to life that evening by a diverse collective of musicians and dancers, writers and artists.

Named after a lost island in the lost Aral Sea whose name, in turn, means “if one goes there, one won’t return,” Barsakelmes felt to me like a decolonial rock opera. I know the latter term is grossly outdated, but I use it without irony or nostalgia. This performance was definitely what theatre professionals refer to as a “show”: both sonic and visual, both popular and refined. It was both scripted and improvised, both archaic and futures-oriented, both overdetermined and deliberately unformed, inchoate but not indeterminate. Within the rhetorical and aesthetic restraints common to all such shows, designed to speak to audiences here and now, it was a mind-opener.

I was particularly impressed by the language-based stream-of-consciousness improvisations by Saadet Türköz, a Kazakh voice artist based in Switzerland whose parents fled from Chinese East Turkestan to Turkey before she was born in 1961. I mention these biographical details because it seems meaningful to me that a Kazakh-speaker who doesn’t also speak Russian should be the one, among all these performers, to reach most deeply into a shamanic substratum of spiritual journeying and mystic transformation.

Among the other performers was Anuar Duisenbinov, Lostans’s editor, reading lines of poetry and wearing a black oilcloth cloak with the shoulders padded out to form a gathering of ancestral masks. I became curious about those poems, in which he uses both Russian and Kazakh, and decided to ask him for a conversation. He told me: “The Russian we speak in Kazakhstan has become a very local language in the last thirty years, and what I write in Russian may not be fully understandable to someone living in Moscow. I will most likely never be included in their circles. But I see no reason to let go of this kind of Russian.”

About Barsakelmes, Duisenbinov said: “We insist on speaking from a position of non-violence, but we also don’t want to be the forever-colonised victims. We should move forward and imagine new futures and challenges for ourselves, but that is not possible if we keep blaming the colonisers.” He stressed the importance of sonic culture in Kazakhstan and in other nomadic Turkic cultures, but also pointed out that colonial ethnomusicologists helped preserve it; the dynastic lines of musicians and shamanic improvisers that kept the tradition alive are now being severed. “Samrat’s mother comes from the aqqu tradition of shamanic speech, where practitioners can often not remember the discourse they have just channeled in a trance-like seance. It is about dialogue with our ancestors. They hear us and help us.” Duisenbinov said that they asked one such aqqu if they could record her, and had even made a first transcript, but that then she refused to let them use it. In the end, the performance by Türköz replaced this text.

The spiritual journey or individual pilgrimage is, as Kudaibergen writes in her introduction to Barsakelmes, “by no means an act of self-exoticisation but a lived practice that many people (well beyond the artistic field) choose to experience in Kazakhstan and elsewhere in Central Asia. It is seen as an integral part of local culture and for many, the trip to baqsy [a traditional shaman] or a small pilgrimage to the sacred places (it can be a mausoleum, a Sufi shrine, or simply a sacred natural site such as a canyon) is part of the spiritual healing process they cannot find in more conventional places.”

Duisenbinov described his own journey to Aralkum, the desert that has replaced most of the Aral Sea, and his quest for the vanished island of Barsakelmes: “I was expecting to find nothing but death and destruction, but I was astonished to see life everywhere there. The air was full of insects and birds. From a non-human perspective, what is happening is a transformation.”

From a human perspective as well, it may be added. Not relying on a narrative of sweeping lines or on the more convenient communication enabled by ‘universal’ languages (incidentally often inherited from a previous coloniser) but instead insisting on the significance of detail and nuance, on local colour on what requires curiosity about the specific and humility about the untranslatable – this, as Tlostanova likes to point out in her texts, means taking a step towards the decolonial. It is no coincidence that 80 per cent of Barsakelmes is in languages other than Russian, mainly Kazakh and Kyrgyz.

It is also no coincidence that two of the twenty richest men in Kazakhstan have chosen to invest in new cultural institutions and let them orient themselves towards what may, in somewhat roundabout terms, be called Western and national values, whether it is blue-chip contemporary art or theory books in Kazakh translation. What everyone in Almaty can see, but perhaps don’t feel the need to say out loud, is that neither Tselinny nor Alma pay that much attention to what is now happening in the ‘Russian World’. Both have, in different ways, answered the seemingly disrespectful question I’m asking in the title of this report.