I den Berlinbaserade Elke Marhöfers filmer uppstår ofta en dynamisk känsla av att flera temporaliteter är verksamma samtidigt. Detta har sin utgångspunkt i att hon utforskar filmen genom att betona dess relation till olika ekologiska proccesser. Här intensifieras en hel uppsättning av materiella geografier, territorier eller «assemblage» kopplade till blivande och förvandling. Marhöfers filmarbeten är huvudsakligen filmade med en handhållen 16mm kamera, men tillhör egentligen varken den etnografiska traditionen, essäfilmen eller den narrativa dokumentären. Genom att tillämpa en «animistisk metodologi» aktiverar Marhöfer en «öppning mot materialitet och kunskapsproduktion som skiljer sig från konventionella, antropocentriska epistemologier och som fördjupar samhörigheten med och banden till det annat-än-mänskliga».

Elke Marhöfer försvarade sin avhandling i fri konst, Ecologies of Practices and Thinking, vid Akademin Valand vintern 2015, och har presenterat sina verk i installationer, utställningar och i biografrummet, men har också föreläst på konferenser som Deleuze’s Cultural Encounters with the New Humanities i Hong Kong och Daughters of Chaos, Deleuze Studies International Conference som ägde rum i Stockholm 2015. På senare år har Marhöfer samarbetat med Mikhail Lylov, som i filmen Shape Shifting (2015), som är inspelad i Japan och där den japanska termen «satoyama» – en gränstrakt/zon mellan ett bergs sluttningar och mer odlingsbart slättlandskap – fungerar som en vektor för ett komplext studium av denna miljös specifika biologiska mångfald.

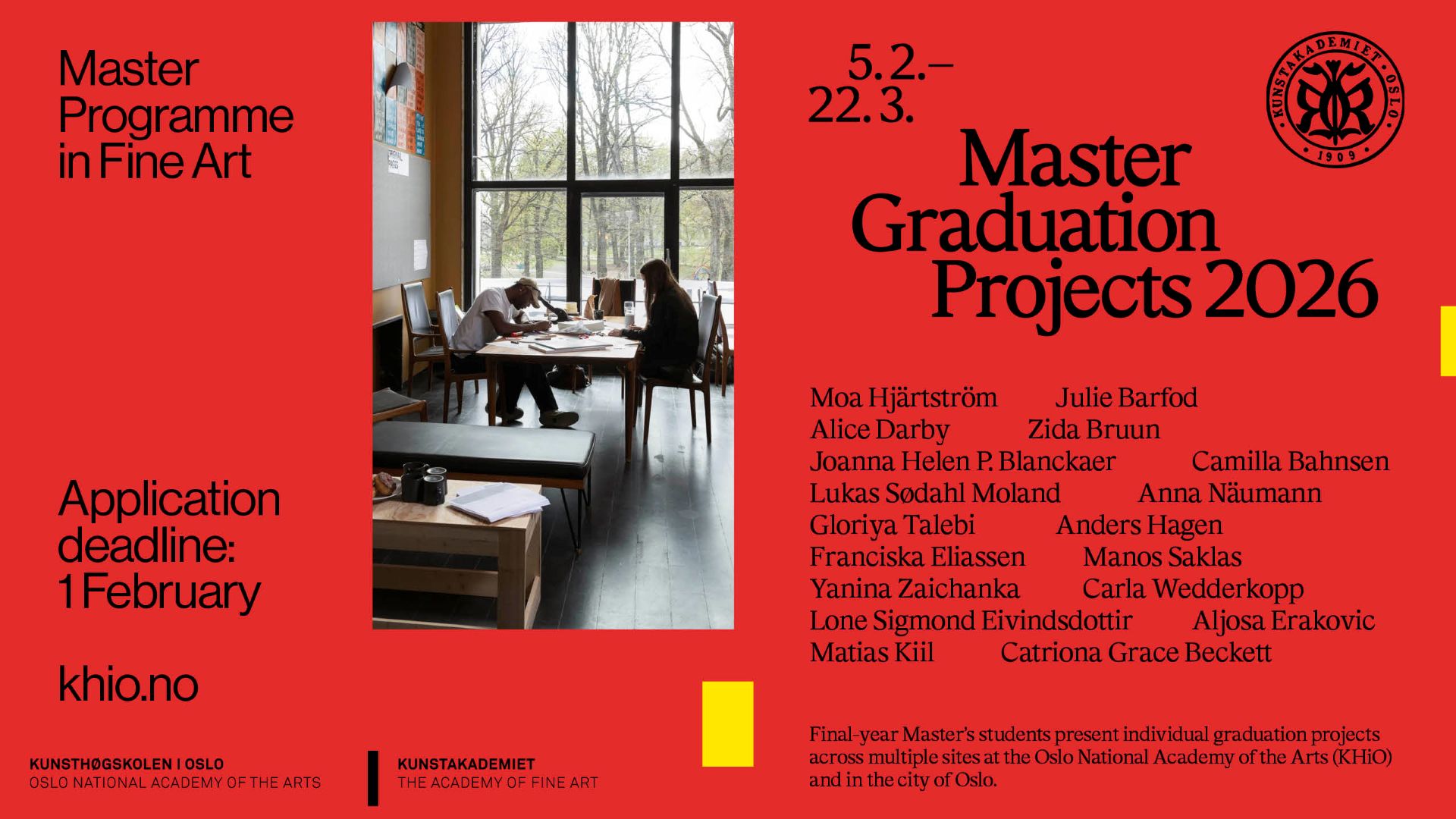

Idag och imorgon kommer ett omfattande urval av Elke Marhöfers filmer att visas i Stockholm – ikväll på Filmhuset/Cinemateket, och i morgon på Fylkingen. Programmen är curaterade av Daniel A. Swarthnas (Turbidus film), och både Elke Marhöfer och hennes samarbetspartner Mikhail Lylov kommer att närvara.

Kunstkritikk kontaktade Elke Marhöfer för att ställa några frågor inför visningarna i Stockholm. Intervjun gjordes på engelska, och publiceras här på originalspråk.

In the written part of your dissertation, Ecologies of Practices and Thinking, you set out to ask what a new materialist film practice can be. In order to figure this out, the text traverses fields of inquiry as different as botany, ethology, the films of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub and an anti-cartesian nexus of affirmative philosophy, from Spinoza, Deleuze/Guattari, Donna Haraway, Isabelle Stengers and beyond. Could you say something about the foundational point of departure for your text and your research?

The text attends to practices and modes of thinking, which involve a sense of attachment to the environment and the more-than-human – in the sciences, philosophy and other forms of knowledge. The first chapter inquires into inherited epistemologies based on anthropocentric and colonial presumptions, and seeks to re-evaluate the hierarchal order of humans, animals, plants and things. By contrast, the last two sections explore dynamic ecological interactions between very different beings that stimulate more complex and fruitful relationalities. My research follows an ethico-political approach that not only pays attention to alternative concepts and practices, but also wants to motivate a direct engagement with the more-than-human. Donna Haraway provides great impulses for this, not only by overriding damages that the disembodied reflection of scientific objectivity has inflected, but by contributing to intense relations, by «becoming with» the other or more-than-human.

You’ve talked about your research as drawing on an «affective cartography» in which different or differentiating relations that connect humans, inhuman forces, plants, animals and (in)organic matter, intermingle in intense «ontoepistemological assemblages». Could you expand a bit on how you understand the workings of these assemblages?

These ecological assemblages are in focus in the last two chapters of the text. There I move towards a diversity of temporalities and processes, as occurs when individuals turn to multispecies assemblages, yet each part retains a distinctive difference. One can find nodes of different species evolving together in food ecologies, in farming and soil practices based on mutually beneficial and sustaining processes. When farmers speak of intense relations with plants or animals, words they usually reserve for close family members, they are immersed in assemblages of becoming with. Through experience they elucidate that animals and plants and things are endowed with inhuman knowledge, or personhood, that soil is enthusiastic, and a landscape cannot be reduced to human-focused productions or conceptualizations.

These kind of immersive, affective relations happen to scientists, too. Natasha Myers and Clara Hustak explore how Darwin is drawn away in a mimetic entanglement with orchids. His intimate relation allowed him to keep pace with both plant and insect practices. Yet these affective ecologies include a diversity of dimensions and temporalities that might be very different from the human scale, or history. The microbiologist Lynn Margulis focuses on endosymbiotic assemblages. For Margulis it’s the interaction of bacteria living inside plants and animals that push evolution. Cyanobacteria, for example, the largest group of bacteria on the planet, have a fossil-record of 3,5 billion years. They triggered the emergence of plants by entering endosymbiotic relations and producing photosynthesis from within other cells. Bacteria, plants and animals entertain these kind of immersive relationships, or ontoepistemological assemblages, allowing them to gain inhuman forces or knowledge.

How and why do you sense that filmmaking is a usable, viable tool in this post-anthropocentric discourse and media ecology?

It seems important to envision and exercise new approaches toward images and their production. In post-anthropocentric conceptualizations images cannot be treated as symbolic representations. Same as matter, images are enthusiastic and endowed with an agential capacity of their own, rather than just being representations of something else. This understanding allows elaborating the complexity of ecological relationalities, where human and not-so-human bodies, soil, air, water and bacteria become media.

The written thesis is accompanied by four recently produced films. On a more general note, how would you say that theory and practice inform each other in your way of working? Do you see any conflicts here?

…the chicken or the egg? No, I don’t see any conflicts between these practices. On the contrary, they enhance each other and still keep a distinctive difference, like other assemblages.

Let’s say something about the formal-material considerations of the films, particularly the camerawork, which is closely aligned with your theoretical positions. A film such as Shape Shifting (2015) shot in Japan, rarely uses pans, but rather uses the camera to literally peer into what’s in front of it. The camera becomes a transitional agent, with its constant modulations and rather rapid movements, its tendency to never really fixate objects in front of it. Could one even talk about the becoming animal of the camera?

Shape Shifting is made together with Mikhail Lylov and focuses on mutual collaboration, human and more-than-human, including the camera. So yes, the camera hardly ever stops in front of something. If it wants to get closer it doesn’t zoom in, it really gets closer. This has similarities with Dziga Vertov’s cine-eye, and his understanding of the world as immediacy, where the camera perpetually has to move, and is a moving body among other moving bodies. Jean Rouch modified the term to cine-trance, shifting the focus to the cinematographer, who while filming actually plunges into a transformation analogous to a state of possession. He or she becomes a mechanical eye accompanied by an electronic ear. One can understand it as a kind of self-technique producing relational sensibilities by immersion. However, I think this trance is not only the trance of the filmmaker, but also that of the camera together with the environment. Elsewhere Jean Rouch uses the term «living cameras», but didn’t follow up on it.

When writing about technology, Jussi Parikka describes tools as an intensive force in environment relations. In this conception the camera turns into a capacity for a practice of ecology. Also Deleuze and Guattari understood tools not as purely man-made, and came up with the great expression «machinic phylum». The machinic phylum is both natural and artificial. It traverses organic-inorganic and social-machinic matter and creates heterogeneities, new inhuman composites. So not only matter and images, but even the camera itself is enthusiastic and endowed with an agential capacity of its own. It breathes rhythm. It never keeps one pace or one affect throughout.

I like to understand the camera as a machinic companion. Companions transform one another. And their entanglement with the environment from which they emerge forms them. This companionship overlaps perspectives of the environment, the camera and the human. It creates a diversity of sensations and temporalities and activates relational modes of perceptions. So you are right, one can say the camera can become animal, but also plant, or microbe…

I’m curious to hear how you would understand your films in relation to a somewhat problematic term like «experimental ethnography»? Your films are certainly not occupied with anthropological fieldwork in the traditional sense, but rather work as affirmative «lines of flights» out of its impasses and reifying representations. Still, are there aspects that you share with filmmakers working with rendering rituals, states of trance, detecting the variable contours of animism found in the work of filmmakers like Ben Russell, Ben Rivers or Fern Silva?

It is difficult to say something about these filmmakers, since they are very different from one another. However, my work might be less human-centered, which makes it also different from most anthropological inquiries. It rather enacts itself as an immediate relation within a territory. I guess filming is to become what Deleuze and Guattari called a haecceity, which is both to dissolve the individual-human-self into an event and to find form immanent to the situated action.

In a statement written to accompany your film No, I am not a toad, I am a turtle! (2012), shot in China and Korea and which will be screened here in Stockholm, you’ve written on what you tentatively call «film chaos». Here you write that it «operates in a space where one obsession infringes on another and exceeds it, thereby dipping into even more chaotic moments. It belongs to the human, the animal, the vegetal and the mineral world that created them. A space where the imaginary is not sheer ornament or subordinated otherwise, but a real source». Could you say something more about the notion of film chaos and its implications in this particular film?

No, I am not a toad, I am a turtle! explores processes of individuation and how those might be encouraged by interferences. So the film doesn’t follow a specific montage structure, or a certain theme. However, it isn’t simply disorder. Deleuze and Guattari refer to chaos as «extrinsic harmonies of an ecological order». That means that animal, vegetal, bacterial and mineral practices of ecology often renew themselves by dosages of chaotic fluctuations, intrusions, and environmental disturbances, like fire, the migration or invasion of species, logging or volcanic eruptions. These accidental processes are able to boost new creative activities.

Film chaos in No, I am not a toad, I am a turtle! investigates how new appearances can emerge through capricious changes. It helped me to find less representational ways of sensing and coming to know. On the level of the viewer, it can be understood as an invitation to let ambiguities, instabilities operate on one’s body, in order to hopefully enhance new thoughts and sensations. In other words, film chaos becomes an event, and a self-technique that takes pleasure in confusion, when attentiveness resonates with the entire body.

In Nobody Knows, when it was made and why (2012–15), filmed at the Warburg Institute in London, you approach the art historian Aby Warburg and his eponymous Mnemosyne Atlas. Here you film the first version of photographic reproductions in the format of 18 × 24 cm, dating from 1928, epitomized by the somewhat fleeting rendering of the panels in the rapid camerawork, its non-fixation, as if accentuating its ruinous or elusive representations. What led you to film this work of Warburg?

Broadly speaking, many texts on Warburg that describe the Mnemosyne Atlas concentrate on the expression of Pathos and the continuation of Greek antiquity through Western culture and history. In those neo-Kantian narratives the images of Atlas are flattened and tamed to symbolic representations, merely assisting the art-historians colossal encyclopedic cartography. They mask the early colonial ventures of Greece to Persia, India and Africa, mantle North European Christian Crusades and the extinction of various practices within Europe, just in order to promote Hellenistic civilization and culture as place of origin for contemporary Europe. However, Warburg actually saw himself as a «seismograph […], to be placed along the dividing lines between different cultural atmospheres and systems». And the thread that traverses the Mnemosyne Atlas is rather the persistence of diverse and manifold ‘pagan’ or ‘animist’ practices.

With the film I wanted to shift the focus in this direction and highlight Warburg’s method of working through discontinuities and antagonistic confrontations of images, which led him to understand their affective capacities. Similar to Henri Bergson, who worked around the same time and understood images not just as passive objects to be studied by an observer, Warburg highlighted that sensation is a back and forth movement between object and perceiver, between interior and exterior, and that images are blocks of affects, which collectively animate themselves. So I worked with a collection of images from the Mnemosyne Atlas stemming from Iran, Iraq, Syria and Jordan, or from uncertain geographies, to suggest an exploration of the Mnemosyne Atlas outside of European cultural history and its self-image. Furthermore, in these images the human does not take a centralized position, but an entangled one. For example, they disclose the intimacy of animal and human bodies — often corresponding to the rays and gravitational forces of the sun, the moon, and other planets. Possibly due to Warburg’s schizophrenic capacities, he understood that the human and nonhuman is shaped by complex relations that might also significantly change what being human means. Recently Philippe-Alain Michaud published an important book, Aby Warburg et l’image en movement, with a foreword by Georges Didi-Huberman that corrects the above-mentioned view on the Mnemosyne Atlas.

Finally, what projects, films or exhibitions are you currently planning?

Currently I am working on a film and research project in Russia on human and nonhuman temporalities and their interconnections. The project explores plant sensing, archeological excavation of horses from Palaeolithic period, and the ecological restoration project of a grassland.

After that Mikhail Lylov and I will be moving to Japan for two years for a post-doctoral research, to continue our inquiry into environmental practices and to render more precisely how disturbances contribute to a sustainable ecology.