Martha Edelheit, who just turned 89, picks me up in her small green Toyota at the last stop of the bus route. She hands me a mask through the window and asks me to get into the back of the car. All the windows are open. We cut through a landscape of fields, through an alley lined with trees that have lost their leaves, and along the shoreline of Svartsjö at Färingsö island outside Stockholm. It’s quite a contrast to New York, the city she moved from in 1993.

Martha shouts how she loves to drive and how crazy driving was in New York; if you can drive there, she says, you can drive anywhere. She parks by the road and gets out, walking stick in hand. She leans it against an old barn as she unlocks the padlock to reveal a white showroom. It is an unexpected sight, judging from the outside. On display are large-scale, colourful paintings, like Seals, Central Park Zoo (1970–71), which depicts life-size nudes, their backs towards the viewer, looking at a pool with seals. It’s a treat to see the water painted like 1970s style batik in Cerulean blue and turquoise. Here are also her humorous double-sided cutout plywood painting-sculptures from the 1980s, featuring provocatively dressed circus performers balancing on horses and elephants.

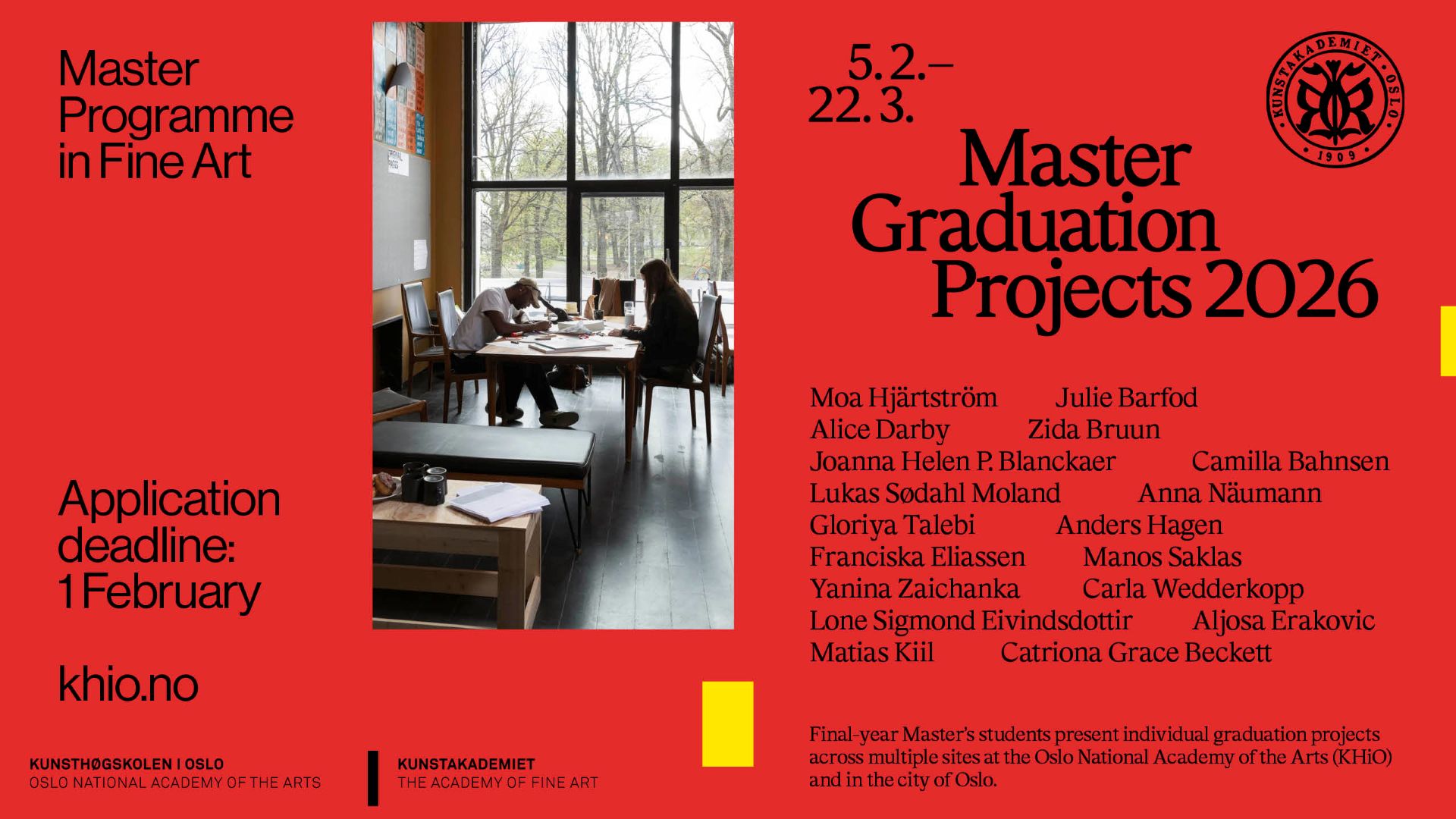

The next stop is Martha’s studio in a rebuilt old wooden house on the broad lawn one hundred meters from her home where she lives with former CEO of Swedish Television (SVT) Sam Nilsson – the reason she came to Sweden. The studio is big and bright with theatre lights in the ceiling. There are paint stains everywhere, intensifying on the floor beneath a wide canvas stapled to the wall. It depicts nudes in different shades of yellows and blues leaning on sheep with hens surrounding them. It makes me think of Martha’s painting Flesh Wall – Female from 1965, a five-meter wide ‘wall’ of nude women reclining against a multicoloured background.

There are a number of different collections in the room: aluminium foil packages for food, seashells, broken wine glasses, and boards in various sizes. Several reference images also hang on the wall, including Vermeer’s The Girl with Pearl Earring and a newspaper clipping with a Frida Kahlo self-portrait. Two drafting tables are covered in paper, ink jars, sketches, and pencils.

“Where do you want me?” Martha asks as I put up an easel which, she tells me, used to belong to Swedish artist Lena Cronqvist. She sits down on a small chair in front of me with her iphone in hand; disappointingly, she lays it aside when I ask her. I’m here to paint her portrait and was asked by Kunstkritikk to interview her while doing so. I start with the charcoal outline as I ask her about her beginnings as an artist, and a time and place that to me always seemed so far away.

How did your artistic activity start out?

I was trained as a musician, actually. My teacher wanted me to be a concert pianist, but I didn’t love that idea. I have always, since I can remember, drawn and painted. I just didn’t call it art. At the University of Chicago, as I was taking classes in poetry, literature, philosophy, and history, I was sketching and drawing at home or in my notebooks. It didn’t really occur to me that I could be an artist. All the artists in the museums were men. Being an artist was sort of like being God. I don’t think I called myself an artist until my forties. I used to call myself a painter. Being an artist was being in the museums, and being canonised, and also probably being dead.

The first living artist I met was Michael Loew. This was in 1954 on Monhegan Island where we shared a summer house. I was in my early twenties and asked if I could draw on the balcony of his studio. I learned a great deal from just watching him work, and I started to take his classes in New York. A year later, also on Monhegan, I met Renée Miller Rubin who was the first female artist I had met. Or that’s not entirely true, I did take a life drawing class at the Art Students League from Peggy Bacon; I was sixteen. That was the first time I encountered a nude model. I was stunned by it, it was incredible.

Anyway, it was through Renée Miller Rubin and Alan Kaprow – who she introduced me to – that I got involved in the art world. This was around 1957. At this time, I got serious with my work. I sublet Michael Loew’s New York studio for a year and quit my day job.

Can you tell me about the art scene during the late 50s and 60s in New York?

In the 50s, SoHo didn’t exist. It was just starting. Instead, the art scene took place on 57th Street, 10th Street, and the [Greenwich] Village. SoHo was an outpost, an industrial area where artists were just starting to move. If an artist lived in a building, they had to have the sign A.I.R (Artist in Residence) on it, so the police and fire department knew someone lived in there.

At this time, the doctrine of abstract expressionism was absolute. For example, one day I came to the Mike Loew class after having seen this fantastic woman in the streets, and I started to depict her from memory. Michael came up to me and said, “you can’t do that” – meaning figuration. I got so frustrated that I threw a can of dirty turpentine at the canvas and walked out. I think figurative work was what I always wanted to do. There were people around doing figurative work, like Mary Frank, for example. But, though I knew her, I didn’t know her work until later. The same with Red Grooms, Mimi Gross, Bob Thompson, Jan Müller and Marcia Marcus. Figurative painting was not Modern Art. And nudes, which I started to do later, were certainly not!

In the 50s, you could count the number of commercial galleries on your hand. By the end of the 60s, there were hundreds of them. In the beginning, there was Betty Parson. She started out showing Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Sari Dienes, whom I later did a movie on. Parsons was a wonderful artist herself. There were the 10th Street galleries and also the uptown Hansa Gallery directed by Richard Bellamy and Ivan Karp who went on and became big gallerists. Most of these were artist co-ops. Renée’s sister Anita Baker started the Reuben Gallery, another 10th St co-op, and I had my first solo exhibition there in 1960.

Those were extraordinary times. One night, a whole gang from the gallery went out after an opening of a George Segal show. There were artists like Jim Dine, Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg, Bob Whitman, George Brecht, and Lucas Samaras. I remember thinking, this is how it must have been like in Zurich in 1914 with all the Dada and Futurist artists getting together, talking about art!

Around then, an experimental art site in Judson church called the Judson Gallery started. It was a really fantastic space with environment, dance and happenings and theater. I participated in a lot of performances and exhibited there myself. At the time, it was a hotbed of endless discussion going on about art. Everybody talked to everybody; there was no real hierarchy. Women artists worked alongside the male artists and were not considered differently. But once the commercial galleries came into the picture, the women artists were pushed aside. All of the males from the artist-run galleries ended up going to big galleries like Martha Jackson, Pace, Sidney Janis, and Leo Castelli. But we women weren’t. We were called women artists and weren’t taken seriously. You weren’t an artist, you were a woman artist. Always.

In the early 60s, after your shows at Reuben Gallery and the Judson Gallery, you took a leap from the abstract towards the erotic and the nude. How come?

Early on, I made erotic watercolours, but they were my private fantasies. I didn’t plan to show them. In 1959, Hank, my late husband, and I made a trip to Europe. We visited all the major art museums and churches, and that made a big impact on me. The first nude I did after that was of myself. I painted a portrait of myself in a mirror hanging on a wallpapered wall, doing a tattoo on the back of a model, who was also myself, the skin being a double canvas. I was really playing around with what was real and what was not real, what is a painting and what is not, Magritte’s “Ceci ne pas une Pipe,” type of thing. It was really what these wallpaper paintings were about. They led up to the large painting Flesh Wall – Female (1965), which came from an urge to work with flesh. Also, I thought it would be interesting to work with models.

I remember I was working on Flesh Wall – Female when my friend Lucas Samaras brought Andy Warhol to my studio. Andy hated my nudes and the erotics; he absolutely hated them. But he loved my wallpaper paintings. That was before he did his wallpaper paintings. I was shocked to see them at the opening of his next show.

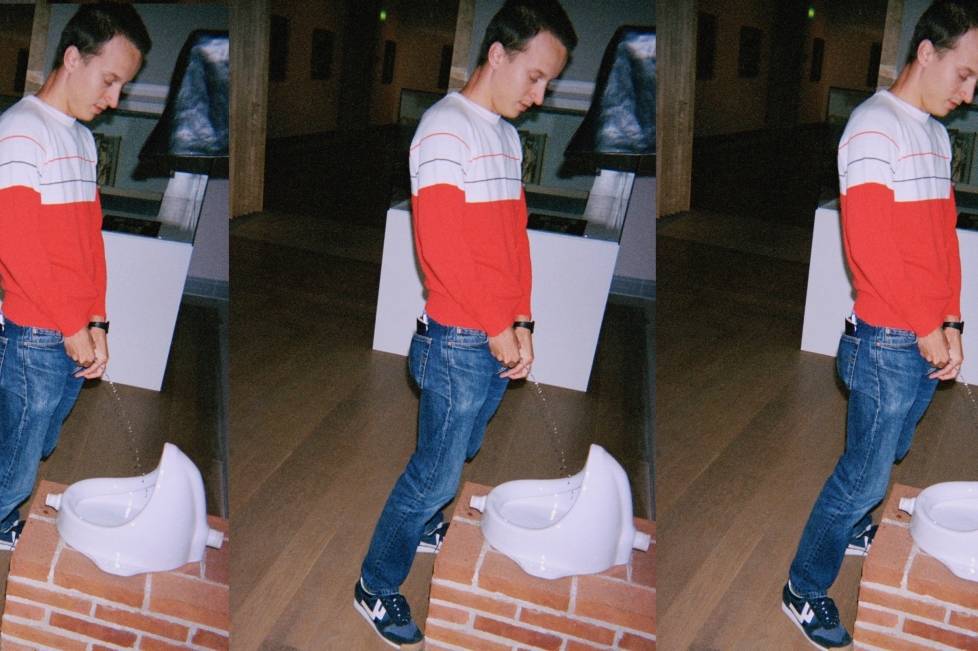

Then I had a show at the Byron Gallery in 1966 that included these works and also a mannequin that I had found on the streets that I cut up and turned into painted sculptures. The main art critic from the New York Times, John Canaday, spent several hours in the gallery, but then said to my dealer that he couldn’t review “that obscene woman.” Artists didn’t do what I was doing back then, not at all. If they did figures, they weren’t doing unclothed nudes. And if they did, they didn’t do male nudes and never female nudes which included the genitals. You could do boobs, but you couldn’t do vaginas or penises.

Talking about the nude makes me think about that painting by Alice Neel of John Perreault from 1972. And also Silvia Sleigh who worked a lot with the male nude.

Well, Silvia didn’t start doing nudes until her husband, the art critic Lawrence Alloway, had been on a visit to my studio and went home and told her to do nudes. Alice Neel was something else. I knew her and her work which was special and unique. She was like Mary Frank, they both followed their own path. Of course, there were other artists doing figurative works or nudes, but they weren’t showing in commercial galleries. Nobody would show them. That’s why my show at Byron in 1966 was a big deal. It was a small community back then, and at my opening the whole art world was there: Leo Castelli, people from the Modern, Mel Bochner, who helped me with the selection for the show. Everybody thought it was going take off, but it didn’t and nothing major got sold.

How was it to be rediscovered, and to have a solo show at Eric Firestone Gallery in New York in 2018, where many of your works from the Byron gallery show were exhibited?

It was sort of shocking, unexpected, and really quite wonderful! I hadn’t expected that. Then, Firestone wanted a new painting from me for the Frieze Art Fair in 2020, and that’s what I am working on now… a bit overdue. He ended up showing A View of the Empire State Building from Sheep Meadow (1970–1972) and Birds: A View from Lincoln Tower Terrace (1974). Painting for me has always taken time, but now it goes even slower. Also, the political news is bringing me down these days, but this painting is coming together – eventually. It’s a delight to work with models again and to combine nudes with what I’ve been working on for the last twenty-five years, paintings of my surroundings with animals. When I came to Svartsjö, I thought about what Rubens had said, “paint what’s in front of your nose.” And so I did.

The animal portraits that you’ve been working on for the last two decades are topical now as the art world has turned its attention to the local and the environmental. Have you shown these paintings or other works in Sweden?

I have had some exhibitions in Sweden. For example, at Wetterling gallery in Stockholm in 1998 and 2001, and at Piteå Konsthall in 2009, where I exhibited paintings of sheep on a base of papier-mâché and chicken wire. But I never really got into the art scene here. There were, as I see it, two problems for me. First there was the language barrier. Secondly, I was terrible busy with Sam’s social life. He was the head of Swedish Television, and every night there were an event to attend. I didn’t have time to nurture my own professional life in the art sphere. To get into a scene, you really have to socialise and go to openings and visit artist’s studios and so on. Also, we lived in Svartsjö. It’s quite far to get into Stockholm. But I did get to know Lena Cronqvist, who is a colleague and a friend, as well as the American artists Susan Weil and her husband Bernard Kirschenbaum, who taught at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. I’ve worked in my studio all this time, but have not been a good promoter for my work.

Can you say something about how Women in the Arts came about, and about the feminist galleries of the time? I’ve been thinking that there isn’t a need for such movement today, that class and race inequality are much more urgent issues. Though, of course, it’s all interconnected. What do you think about the art scene today? Has there been progress?

Well, the only way for us women artists to exhibit was to show our works ourself, through our own venues and groups. First, there was Women in the Arts, an organization of women artists dedicated to promoting change and equity in the art world. It included all art forms, and we were eight people at the first meeting in 1973. But it became very clear that the writers and artists had different problems. The female writers had to put up with four martini lunches with editors and publishers, lunches that ended up in bed. Women artists couldn’t even get into the front door of an art gallery. So the group became just for the sculptors and painters, and already by the fifth meeting we were four hundred women artists. I mean, it was that desperate. It included people who had been around for a long time, like Elaine de Kooning. Every female artist I knew was a part of Women in the Arts. Maybe Helen Frankenthaler wasn’t; she was already successful and came from money. And neither was Georgia O’Keeffe, who was enormously successful and famous. But even O’Keeffe told me how she got treated, at the Whitney Museum for example. It wasn’t good.

Towards the end of a meeting with Women in the Arts in 1973, Rosalind Schneider asked if there was anyone who made films, and I vaguely raised my finger. I had just done this one film. So we met up after the meeting with Susan Brockman, Doris Chase, Silvianna Goldsmith, Nancy Kendall, Maria Lassnig, Carolee Schneeman, Rosalind Schneider, Olga Spiegel, Alida Walsh, and we started Women Artist Filmmakers. It was a wonderful experience, because as an artist you’re alone most of the time. With this group, we worked together and we started to introduce films in our exhibitions.

A.I.R. was the first feminist co-op gallery, which started in 1971. I never joined because they rejected me. I was pissed off because of that, but later they were eager to befriend me. I also had the problem of being married to a doctor, a psychoanalyst. I never got any grants, and Rosalyn Drexler told me how they talked in the committees about me being married to a doctor and didn’t need any support. So I stopped wasting my time applying for grants. Anyway, I did have an exhibition at A.I.R. gallery in 1984. I also became a member of SoHo20 in 1984. It was the second feminist artist gallery by and for women. We did some fantastic stuff, really. One of the best things we did was to show works of senior women artists, because the art world was and still is really a young man’s world.

My sense is that, for all the changes that there have been, there is an endless and unending uphill battle that is never going to end. It’s like being Black in the white world: you’re always going to be a second-rate citizen unless you fight tooth and nail not to be. The same if you’re a woman. And that’s universal, in every culture, no matter what they say. I mean, there are changes and it’s better now, but every time the Guerrilla Girls go out and do a count of women artist shows and museum purchases, it’s still miniscule.