Lørdag 14. november åpner en utstilling med den britiske kunstneren Martin Creed på galleriet Peder Lund i Oslo. Creed (f. 1968) ble kjent for et større publikum i 2001 da han vant den britiske Turner Prize for verket Work No. 227, The lights going on and off (2000). Verket besto av tidsinnstilte lyspærer, og gjorde som beskrevet i tittelen ved å vekselvis mørklegge og opplyse rommet i intervaller av 5 sekunder.

Work No. 227 (Creed har nummerert verkene sine siden 1986), har blitt den britiske tabloidpressens yndede eksempel på samtidskunsten sjarlataneri. Pressens tidvis fiendtlige holdning til Creed er egentlig merkelig, for verkene er ofte humoristiske, generøse og lettfattelige: Han har omgjort trappene i The Fruitmarket Gallery i Edinburgh til tangenter som spiller forskjellige noter når man trår på dem; Work No. 850 (2008) besto av sprintere som spurtet gjennom en av Tate Gallerys haller hvert 30. sekund. I fjorårets retrospektive utstilling på Hayward Gallery i London sto det en Ford Focus på takterrassen som ved jevne mellomrom automatisk åpnet alle dører og satte på radio, horn og vindusviskere, som om den brått våknet til live. Under åpningen av OL i London i 2012 var Creed nær å få gjennomført det umulige Work No 1197, All the Bells in a Country Rung as Quickly and Loudly as Possible for Three Minutes.

Creed er også musiker og har en tilnærming til popmusikk som ligner den han har til kunsten. Sangen Thinking/Not Thinking består for eksempel av kun to akkorder som representerer hver av de to bevissthetstilstandene.

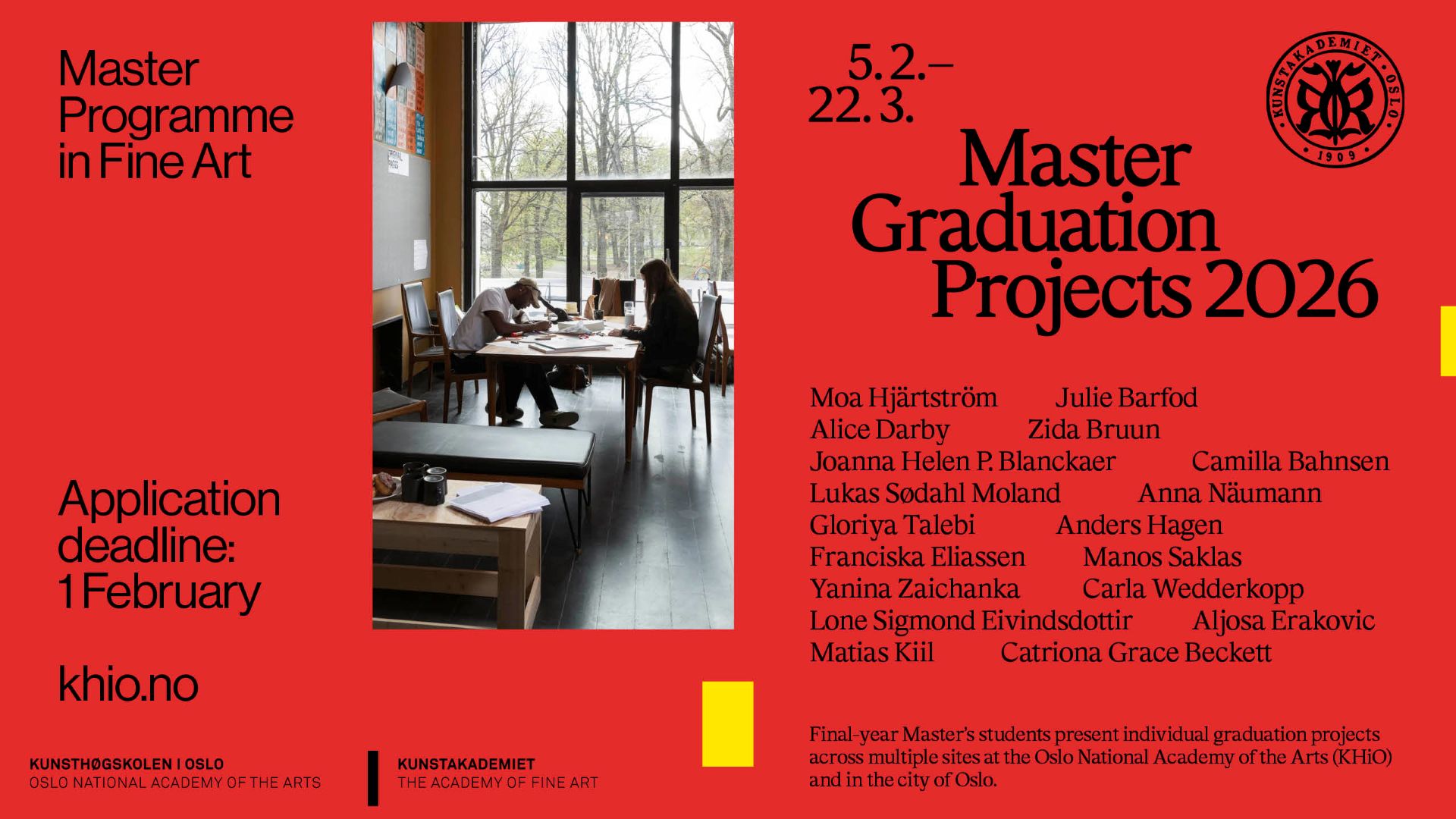

Da Kunstkritikk ankommer galleriet sitter Creed og spiser lunsj iført en beige tweedjakke fullstendig tilsølt med malingflekker. Creed, assistenten hans og to dansere har nettopp gjort ferdig et av maleriene som lages in situ på Tjuvholmen. På veggen henger et oppspent lerret og en beskyttende plastduk som er totalt dekket av striper av maling i forskjellige farger. Det er fotavtrykk etter danserne omkring på plastduken og en grumsete vannpøl på gulvet. Det ser mer ut som åstedet for et wiener-aksjonistisk ritual enn forberedelsene til utstillingen til en kunstner som er kjent for konseptuell stringens, for eksempel å organisere objekter etter størrelse.

I tillegg til utstillingen på Peder Lund skal Creed vise malerier i foajeen på Kunstnernes Hus, der han også holder en artist talk torsdag kveld. Creed har en særegent avvæpnende taleform, som han også benytter i sine stand-up-lignende artist talks; han er springende, nølende og nervøs, og kan tidvis fremstå som litt naiv. Men innimellom bryter han ut i en mild latter som får en til å mistenke at han fremfører en slags performance.

Intervjuet gjengis på originalspråket

You’re showing paintings both here at Peder Lund and at Kunstnernes Hus?

– Yes, we use a similar approach, but the works at Kunstnernes Hus will be painted on glass. We’re trying to get all the colours onto the surface without controlling it too much. Usually with works like this we set some rules in advance, and then we try not to get in the way of the colours and the shapes. Things that aren’t very good are usually too controlled.

I once heard you talk at a screening of Work No. 610, Sick Film (2006), which basically shows a group of people vomiting one after the other. I was surprised to hear you describing throwing up as a metaphor for creation. This is quite a romantic notion, that art is something natural that forces its way through you. Do you consider art to be an involuntary, almost biological function?

– Yes, absolutely. Basically I feel bad, I make works because I want to feel better.

A lot of your work seems to be about choosing an object or a phenomenon and presenting it in accordance with an inherent logic – like the work where you made a wall out of all the different types of bricks you could order (Work No. 1812, 2014). Do you know what the works will look like in advance? Do you make sketches?

– Well, I make a lot of notes in notebooks, or record voice notes. For a painting like the one we just made for the show here, the planning will be verbal or written. And from that point on, taking it into the world involves bringing in different materials and working with other people. It also depends on whether there’s an opportunity to make a work. I worry about making works just because I can; one thing leads to the next and I get offered more shows. I used to think: «Oh no, another show!» But it’s not necessarily a bad thing; sometimes the best work comes out of just getting somewhere at nine a.m. and doing the job. And sometimes the worst work comes out of really wanting to do something.

I suppose this way of working involves quite a lot of risk, not knowing whether an exhibition will work or not. With procedural works you can’t know the results in advance.

– The reason I do this kind of work at the moment is because I’m sick of planning things. The planning involved in the works here in Oslo is simply done in order to enable us to make them two days before the show. In a way, this way of working comes from doing live shows in theatres and music venues, and taking that approach to the visual works. It’s about thinking of an exhibition as a live event, or as if we were a band coming in to record an album.

Martin Creed, Work No. 1090, Thinking / Not Thinking.

I’m curious about the numbering of the works. At your website the latest addition is Work No 2325. By dividing that number by 29, the years from the first to the latest work, it adds up to 7,5 works a month. What qualifies something you do to go into that list? Do talks have numbers as well?

– No, the qualifications are purely pragmatic and have to do with the works needing to be identified; it’s usually the point at which something goes into the world. A talk is always a work, but also contains many other works. But it wouldn’t necessarily get a number – or maybe it should get a number? I started doing the numbers because I didn’t want titles, but rather to treat everything equally. I try to work in the light of the thought that I don’t know best what the works are about and what kind of effect they will have on other people. There’s a lot more that I don’t know than I do know. Any knowledge I have is basically just a drop in the ocean, so I may as well say that I’m stupid.

Like a Socrates…

– If you think about it, a work needs to be a bit stupid to be good; then it will be more like life. And the worst works are works that deny life. Then they just become commodities.

I’ve actually installed one of your works in a gallery once, a text work made with vinyl letters which reads «the whole world + the work = the whole world.» I was very puzzled by that phrase.

– Oh, really? Why? It’s just straightforward.

Well, that’s exactly it. It’s completely straightforward, but still confusing. My take on it was that the work was just an addition to the totality of the stuff that makes up the world. But now that I have the opportunity to ask, what were your thoughts about this piece?

– To me it has to do with thinking that whatever you do cannot be separated from the world. Everything has an effect on the world and is part of the world. The equation just tries to describe that. I came up with the phrase when I was filling out an application form where you had to include an artist’s statement. So I sat down to describe my work and what I came up with was that equation. Later I thought it could be a work in itself.

Last year you had a big retrospective called What’s the point of it? It’s a title that puts words in the impatient spectator or critic’s mouth, but it’s also an existential question for an artist. Do you ask yourself that question?

– Yes, it’s a question I often ask myself. It’s quite clear to me that the point of it is to make life less boring, you know. More fun or interesting.

And a retrospective is a good occasion for questioning what you do?

– Some people think that you can somehow reach a point where you know something, but I’d rather keep trying things out, experimenting and asking questions. I hate it when people think that they’ve reached a sort of plateau of knowledge.