I would’ve liked to visit the dean or head of department from time to time, but it’s hard because we’re in separate zones and the students don’t have access to the administration. It would’ve been nice to have been able to just go and ask when you’re wondering about something.

We have come to know an art school by its brightly lit, convoluted, and messy spaces full of second-hand furniture, graffiti, makeshift walls, and smelly refrigerators. In the often chaotic student studios you would find materials, works of art, and garbage liberally scattered around, and telling the difference could be difficult. The art school was an indefinable zone of freedom, created year after year out of layers upon layers of artistic work. This architecture served as a backdrop for the artist of old: a somewhat inarticulate individual who achieved insight through their singular, introverted practice, and whose main workplace was the studio. At the old art school, art students came across as people for whom health and safety protocols, due notification procedures, or adequate lunch schemes were entirely irrelevant: they lived in worlds of their own, would often work through the night, and had no specific duties as long as they submitted a work for the graduation show. It was a strange kind of school where all demands were unwritten and where the main goal was to safeguard and pass on the Olympic fire, i.e. art.

By the turn of the millennium, most art academies and art schools in Scandinavia were independent institutions with a structure that was more or less based on the so-called “professor school” model in which students belonged to a given group headed by a specific professor, and the vast majority of teaching and evaluation took place within this group. Often, all of the professors sat on the admissions committee, picking out the students they wanted; they had their own budgets and were free to teach and lead their groups as they pleased. This model had its flaws and shortcomings: it was authoritarian and hermetic; the teaching differed hugely and was wholly dependent on which professor you ended up with; and once you had a professor, you were stuck with them. Harassment cases were common, but were rarely acted upon. Few outsiders had insight into how the teaching was conducted.

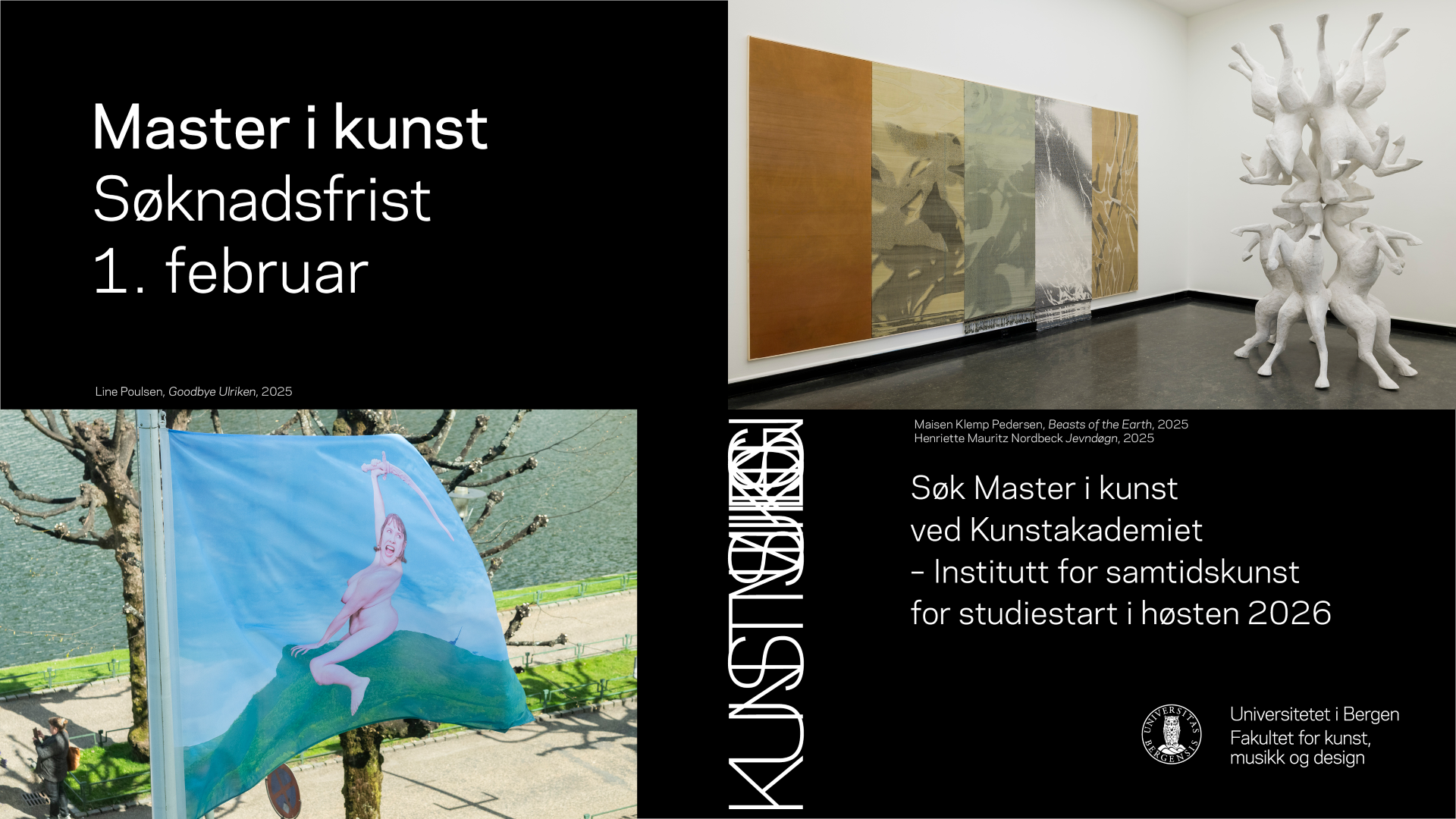

With the exception of Denmark, this model is now almost extinct in the Nordic countries. Art academies have become faculties or institutes under the auspices of larger merged units, either through incorporation within pre-existing universities or by fusing with other institutions specialising in aesthetic/artistic disciplines. Concurrently with these mergers, art schools have, to varying degrees, implemented reforms outlined in the Bologna Accord for standardising higher education within Europe and adapted to match national and European qualification frameworks. Between 2000 and 2010, the “professor schools” were replaced by coordinated admission procedures, shared programme budgets, looser affiliations between students and teachers, interdisciplinary courses, and a number of follow-up routines that are common to all and serve quality assurance purposes. In the last ten years, this development has quite literally been cemented in the form of prestigious new builds or costly renovations of old factories repurposed as the new homes of art programmes. A total of seven art academies in the Nordic countries have moved to new or newly adapted buildings, and at least three are currently undergoing a relocation process (Malmö, Valand, and Helsinki). In Norway, this has happened to all four art academies: Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, and Tromsø. When you enter these new buildings, it dawns on you how fundamentally art education is changing.

A special feature that the new art schools share with all contemporary public and corporate construction is the large, open spaces: airy entrances, atrium courtyards, and project halls. This spaciousness confers upon art education a status it has never held before, communicating artistic practice as a multifaceted and spectacular activity. There are financial advantages to not having a given discipline locked into specially designed facilities that then run the risk of being underused. First and foremost, however, these areas express an ideology of openness, interdisciplinarity, flexibility, and cooperation associated with the “sharing economy.” As the architectural office Snøhetta writes about the newly built Faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design in Bergen: “Another important feature of the building is its unifying mission, manifested through the project hall. As a powerful symbol of the unification process of six faculty buildings merging into one KMD, it is a direct reflection of the faculty’s ambition of stimulating collaboration and cross-disciplinary exchange.”

The new art school buildings in the Nordic region are characterised by precisely such huge spaces that can potentially be used for everything from public concerts and performances to project work, meetings, downtime with your laptop, carpentry, and getting from one place to the next. As much as they offer flexibility, they also incite the students to take on a new role, one where they learn the fine art of navigating between work and leisure, socialising and study, constant availability and ceaseless performativity. The shabby painting studios we were all so fond of, with their heavy doors slamming noisily shut, have been abandoned and replaced by bookable and multi-functional rooms.

Glass floors

When I’m at my workplace at school, I start to behave the way I think an art student would behave. If I’m doing carpentry, for example, then I think ‘now it looks like I’m working’. I pace back and forth because I think it looks good, like I’m being productive and know what I’m about.

The focus on openness is reflected in the use of huge glass surfaces combined with vast project spaces and features like Plexiglas floors. Staff and students are increasingly observing each other as they work. In Bergen, student workplaces have been moved down into the atrium yards where they can be viewed from above. In Tromsø, the walls of the student studios are made of glass, making them useless for working. This transparency is commented on in all analyses of what may be called “neoliberal architecture.” In his book, After the Great Refusal (Zero Books, 2018), Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen describes Zaha Hadid Architects’ BMW factory in Leipzig: “The workers are precisely not monitored, but effect an ongoing control themselves … Instead of an external power overseeing the plant, we have a transparent and dynamic space in which workers are always visible to each other, communicating and participating in production.”

Concurrently with the architectural arrangements to ensure monitoring and, thus, self-control, countless other control options have been implemented at all levels of the institutions. The proportion of administrative staff has increased dramatically as various institutions have begun cohabiting (obviously, the argument claiming that mergers would reduce bureaucracy did not pan out). Let us consider an example: in 1996, the small art school in Umeå had two professors and two administrative staff. In 2020, the number of professors has dwindled to one, while the ranks of administrators have swelled to six, a staggering 300 per cent increase. The merged institutions have outsourced core functions such as IT, cleaning and operations, which require added levels of co-ordination and handling. Management strata are set up to govern specialist departments without having any direct knowledge of the field, which only makes their affinity with the ministries’ requirements on documentation and evaluation all the keener.

The art field itself never developed its own discipline-specific evaluation criteria outside the artistic sensibilities and discernment of professors and fellow students, and when such assessments suddenly had to be standardised and documented, educators resorted to traditional academic tools such as credits, course structures, and exams every semester, all the way down to minutia like a required number of supervisory sessions per semester. This development is symptomatic of a general weakening of the professors’ and specialists’ power within the field of art education. In part, their authority has been eroded through direct political changes such as larger numbers of external members on various boards and the introduction of parity between elected and appointed rectors. Another reason is the ever-mounting bureaucracy. We might also want to think about the fact that while the specialists/professors – those who know about art – are predominantly employed on fixed-term contracts, everyone in the administration is tenured. Thus, the administration becomes the permanent staff who come to represent stability in the schools and, eventually, embody institutional memory too.

A distinctive feature of the new art school buildings, then, is a schizophrenic mixture of openness and ceaseless monitoring. The long corridors and heavy doors are long gone, as are the closed façades with entrances known only to insiders. Arriving at the new art schools is like approaching a public cultural institution, entering via a vast entrance hall through sensor-operated doors(the architectural prospectuses call particular attention to the seamless connection with the outside world; the lack of a threshold). At the same time, you can be monitored by the architecture itself, via key cards and in some cases surveillance cameras. While tracking an individual’s movements in a given building is illegal in the Nordic countries, key cards still enable security personnel to map general patterns of movement and check who, if anyone, has entered a specific room. During the current coronavirus crisis, this became a useful tool: it was easy to see where the key cards were used, so if people were going places they shouldn’t, they could be denied access altogether – a threat easily carried out by simply blocking their cards. What is more, you can be monitored digitally: on the learning platform Canvas, which is used by most art programmes in the Nordic countries, teachers can check whether their students have read assigned texts or filled in evaluation forms, while the IT department has access to every single PC issued to members of staff.

Contrary to neoliberal organisational ideology, where the boss should ideally circulate among their staff and cultivate a ‘buddy’ image, the hierarchy of the institution has been deliberately reaffirmed by placing administrative staff, academic staff, and students separately, and barring student key cards access to the school’s management area.

Where’s the kitchen?

I don’t need that much, really. I mostly write and draw. A window to look out of, and a kettle. And I would’ve liked a mattress, I need to lie down to rest from time to time.

The issue of student studios has been a recurring problem in the new art school buildings as well as in rehabilitations of old ones. The building processes demonstrate a lack of any clear idea of what a student studio is and what it takes to make it work. In several cases, construction has been launched based on the attitude that students should work in open landscapes. Soon, however, it dawns on everyone that no art students can work that way, and the open-plan offices are transformed into labyrinths of lightweight walls, giving each student a tiny cramped cubicle in which to work. It seems that entrepreneurs and architects find it so hard to accept that the students want their own private workplace that they refuse to comply before the need is absolutely urgent. The practical and financial reasons for this probably have to do with the fact that private spaces require more square metres, but the official line is that the open-plan offices reflect a desire for greater openness. A critique of the new art school in Bergen printed in the Norwegian architects’ journal Arkitektur N (nr. 8, 2017) makes for an interesting read. Pernille Akselsen writes:

The art students have wanted their own private rooms, and got their wish in the form of white fibreglass walls that create small rooms arranged in a row. This does not appear to be sufficiently private for most of them, since the spaces have been further sealed off with rugs and textiles. The cubicles form a stark contrast to the open-plan office of the design students. I am told that the walls are not just about achieving concentration, but that art students have a need to physically retreat. Either this is an ingrained culture that has tagged along from the previous building, or it is a real need for this particular field. Whatever the case may be, the result is corridors of white walls that block the daylight and impede visibility. As an outsider, one struggles to understand how this solution was arrived at. The walls allow a culture that is about ‘me and my thing’ rather than knowledge-sharing and openness. It is neither an inspiring environment nor architecturally beautiful.

Here it seems as if Akselsen wants to strong-arm students into “knowledge-sharing and openness.” In the new educational institutions devoted to art, not being “open” is the deadliest sin. However, it is true that students are sitting in far too cramped studios without proper light or ventilation. In several cases, schools have had to rent premises outside the new building or annex atrium courtyards and workshops as student workplaces. The situation is an all-too-clear example of the strong ideological foundations that underpin the new architecture of art education. The British architectural firm DEGW’s influential 2004 text on the new universities, the ‘User Brief for the New Learning Landscape’, states that “traditional categories of space are becoming less meaningful as space becomes less specialised, [and] boundaries blur … Space types [should be] designed primarily around patterns of human interaction rather than specific needs of particular departments, disciplines or technologies.”

Shared kitchens have been replaced by canteens or cafés. Health and safety rules are rigidly enforced, often because the buildings are rented from private owners who want to ensure maximum security and minimal wear. Students are therefore directed to buy their food instead of making it themselves. Not only does a lack of shared kitchen facilities make socialising more difficult, it also imposes financial demands and contributes to the pervasive performativity mentioned above; one acts as a customer at a café rather than as an artist at work. All this conveys a rejection of the old art school’s ideal which aimed to have the student’s situation mimic that of an established artist in their studio as much as possible. What is more, the canteens close early, emphasising how the artists’ age-old habit and privilege – working throughout the evening and night – is not supported by the institution. A beautiful exception is the art academy in Tromsø, where a large and luxurious kitchen has been installed in the middle of the building, open to all students and teachers.

Reklamarchitektur

When I became a research fellow, I think I spent the entire first year trying to understand what artistic research was. Nobody could explain it, really, even though we read articles about it and talked about it all the time. In the end, I just had to put it aside and do my art.

The new art schools often boast wonderful workshops and resources for the students; they have high-end 3D printers and rows upon rows of Macs. When the Oslo National Academy of the Arts moved into a former canvas factory, the largest ceramic kiln in Northern Europe was installed there. The main reason underpinning these acquisitions is probably that the investment budgets are ample, while the operating budgets are getting leaner and leaner, so in ten years’ time the picture may be quite different. Whatever the case may be, this focus on technology seems exaggerated for fine arts programmes, which are still primarily about gaining artistic insight through fairly simple means. Somewhat speculatively, one might entertain the idea that this focus on technology has arisen concurrently with the emergence of a new artist subject: the artist as researcher. Huge EU investments in research, innovation, and technology have also reached the realm of Scandinavian politics, and over the past ten years most of the new resources within the field of art education have gone towards setting up PhD fellowships at art schools and to research funding for academic staff.

The advent of artistic research has an interesting duality. On the one hand, it has opened up great opportunities for artists who can immerse themselves in a project for several years. It was important to ensure that art education was not left out when all the other programmes got their PhD schemes. Indeed, important battles have been waged within these programmes, championing artistic practices and art’s distinctiveness. On the other hand, artistic research has not been able to escape an academic feel that may eventually cause it to become unmoored and drift away from the rest of the art world. Peer-reviewed journals within the field have sprung up, such as the Nordic Journal of Art and Research and JAR – Journal for Artistic Research, as well as initiatives like the European Artistic Research Network (EARN), which mimic established academic formats from university life.

This may have been necessary to convince funders (i.e. the countries’ respective ministries for education and culture) that there is a network in place to receive the results of the research. However, for the rest of the established art field this discourse seems far removed and irrelevant. Neither the art market nor the museums, nor the artist-driven and alternative scenes seem particularly interested; they might well exhibit the art projects, but rarely engage with the dissemination of the research results as such. One consequence of this is already becoming apparent: a loss of language. Professors and associate professors now call their artistic endeavours “research,” while the art they create becomes “research results.” To this we may add requirements concerning the dissemination of their research, prompting an overproduction of books and seminars to discuss the art projects. This, of course, changes their relationship with their own practice as well as those of their students, giving rise to a reassessment and shift in the field’s established quality criteria and the principle of art’s intrinsic value.

This focus on artistic research may eventually divide Nordic art education into two camps: those who were quick to realise what artistic research offered in terms of financial and organisational benefits for the institutions, and those who did not. In Denmark, for example, the art academies fall under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture, which has shown no interest in introducing a PhD scheme. Thus, the art schools have no accreditation of PhD candidates, and the few research positions there are in Denmark are funded by a private foundation, Novo Nordisk Fonden, while the supervision is carried out by university academics.

When seeking to gauge where artistic research is headed, it can be useful to look to academia. Ever since the art academies were first set up, the professors’ practice outside of the actual teaching has consisted in their own – more or less individual – artistic endeavours. Those artistic activities may have been deeply introverted or transgressive, their merits assessed and validated only through the professors’ participation in and position on the art scene. Now, the guidelines issued by research councils hint at ever larger research projects, often involving overarching themes, PhD fellows and several different partners. This is to say that the funding available is aimed at institutionally orchestrated projects rather than individual practices. Even now, much artistic research has taken on a hybrid quasi-academic form and is presented and disseminated in closed forums. In the longer term, one may envisage a number of more dramatic consequences: the staff’s artistic practice may be steered in certain directions by the granting or withholding of research time and funding; we are likely to see the introduction of specific methods for measuring academic performance where every exhibition or publication is awarded points or credits (ranked according to principles pertaining specifically to artistic research), and MFA programmes may increasingly be aimed at a subsequent PhD degree, with all that this implies in terms of formatting, documentation, and text production.

But let us return to the new architecture of art schools today, which to many of us seems so incomprehensible and exaggerated. In certain ways, it is an example of what is known as reklamarchitektur, or “advertising architecture,” meaning architecture as a direct agitational expression of a certain ideology. So what does it advertise? It is not genuinely neoliberal in the sense of being “adapted to the art market.” Even though it promotes the entrepreneurial artist through multifunctional hub spaces, the poorly equipped student studios testify to little emphasis being placed on individual careers. The new art school’s ideal figure is not the biennial or gallery artist with high profile projects around the world. Rather, this is a case of “propaganda scenography” promoting a vein of new managerialism with a slant towards public funding. It is architecture created for the project manager – a team leader of a research network, for example. This ideal person does not need a personal workspace, but can work quite happily in open-plan offices, formulating project descriptions in collaboration with research clusters throughout the European Union. They are at the forefront as far as specialised technology is concerned, but also very open towards working across different academic disciplines – if not in practice, then at least in theory. They like to eat in the canteen, are good with digital platforms, announce their need for a conference room well in advance, do not spill things, and do not make a mess. They go home at 17:00.

Ane Hjort Guttu (b. 1971) is an artist based in Oslo. She works in a variety of media, but has in recent years mainly concentrated on film and video works, ranging from investigative documentary to poetic fiction. Hjort Guttu is also active as a writer and curator, and she holds a position as professor at Oslo National Academy of the Arts, department of Fine Art.

Part of this article is inspired by a workshop organised at KMD Bergen in collaboration with Sveinung Unneland, as well as Victoria Gouzikovski’s research that examines the KMD building.