At just over 30 years of age, American born London-based artist Issy Wood already comes with a complete mythology: her early brush with modelling, struggles with eating disorder and body dysmorphia, substance abuse and sobriety. Maybe even more prominently, there’s also her rejection of powerful male mentors (pop music producer Mark Ronson and legendary art dealer Larry Gagosian, although she has since 2022 been showing with similarly legendary Michael Werner alongside her longtime London gallery Carlos/Ishikawa). All this feeds the narrative of a vulnerable, but ultimately strong artist capable of dictating the terms of her own work. But is that the whole story?

A day after the opening of her first solo exhibition in Germany, the gallery assistant at Schinkel Pavillon beamed and proudly stated, that the opening was attended by well more than a thousand visitors. The other hot spot of the night was just down the street, at Julia Stoschek Foundation, where the collector and her team pulled off the remarkable feat of giving none other than Mark Leckey his largest exhibition in Germany to date. In interviews, Wood often namechecks Leckey as a formative influence: he provided the role model for the art students in her BA course at Goldsmiths College. Their intense focus on video installation gave her the freedom to finally decide to do the uncool thing and… paint.

And paint she does. In Berlin, the result is an unabashedly conventional – some say classical – painting show. Which is not a bad thing. It features twenty works in oil on canvas (with the exception of a few painted on velvet) and a room-filling installation of painted instruments (MUS1C, 2025) immersed by a subdued acoustic backdrop comprising what sounds like a collage of sketches of song ideas on the upper floor (SCHINKEL.WAV, 2025). Wood is also a prolific and quite interesting musician, and an intensely active blogger.

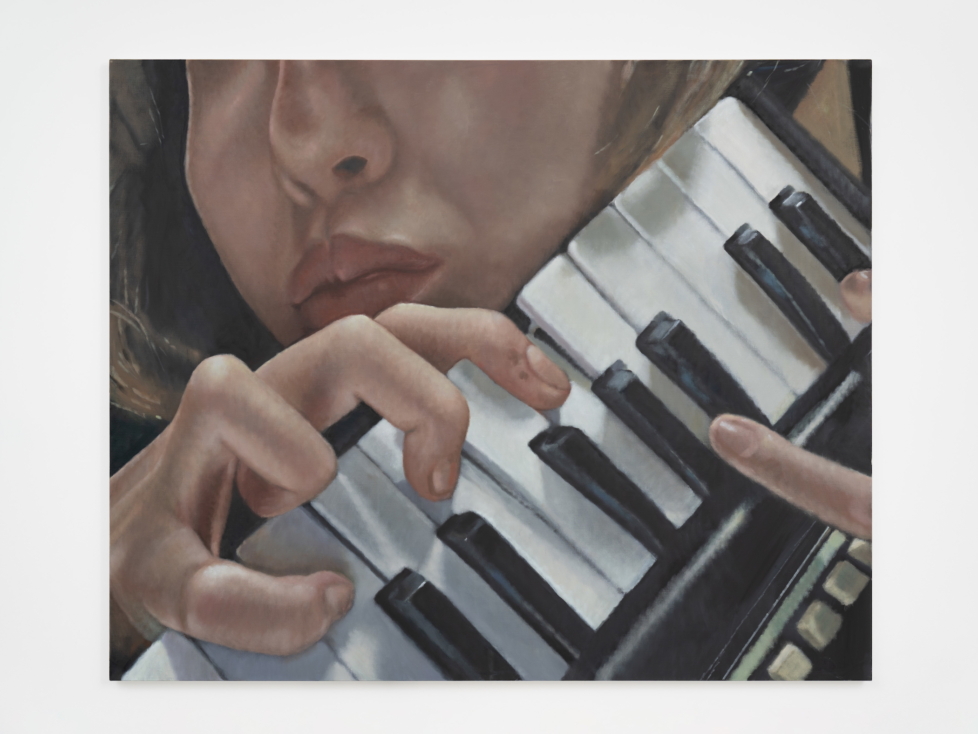

The works on the ground floor are spaced out evenly; their clashing images of jarring and edgy subject matter are especially effective in the small, tiled rooms. A medium-format work showing a monumental plaster cast of teeth with braces (Slouching towards the maxillofacial unit, 2018) is placed next to a barely A4-sized painting of a snarling dog in chains eyeing the viewer (Friendly Dalmatian study, 2021). More than two metres wide, the largest painting in the show is of an opulent arrangement of white chinaware adorned with birds and plants (D1nner2, 2025). Most of the work in the show is absolutely current, dating from this year, such as a large self-portrait in which outsized hands playing a keyboard conceal artist’s face (Self Portrait 64, 2025).

The source material for Wood’s paintings comes from her own snapshots and video grabs, but is also culled from sources as diverse as auction catalogues, fashion magazines and medical journals, and websites for car aficionados. An eroticised focus on surfaces, shiny fabrics, glossy china, leathers, and the interplay of soft velvet and dried oil paint, goes beyond any Pop art superficiality. Instead, reviewers often detect psychologically charged illustrations of a personal emotional narrative that could be interpreted as the voice of a generation of millennials. Somehow, this feels too easy.

Circling through the show, three stylistic decisions emerge. One is the artist’s colour palette: in many paintings, her shades appear dim, even murky. Clearly, she consciously steers clear of bright hues and rather aims for somewhat offside, misty shades; the works in the show channel Luc Tuymans or Wilhelm Sasnal and create a comparable uncanny atmosphere.

Second is the application of paint. Wood paints alla prima, a wet-on-wet technique executed mainly in one layer of short, dabbed brush strokes. This produces effects characteristic of photo-realist paintings – which these clearly are, even if the quirky subject matter distracts from this – as if the smartphone camera had been completely absorbed by the human body. Getting closer to the work, motifs become increasingly fuzzy and eventually dissolve. This makes it fun to watch viewers finding the right distance: younger people instantly whip out their phones and snap away, as if in a moment of recognition. More seasoned viewers go up close, examine structures and study painting technique before reluctantly pulling out their phones to take pictures anyway. Wood’s technique has often been labelled academic, even masterful, but this seems beside the point. Rather, because the dabs are so similar throughout the paintings, this mode of painting appears more like the application of a filter on a camera app – a visual umbrella of sorts, giving every subject the same treatment. It makes me wonder if these paintings are about their subject matter at all.

The third and most striking stylistic element is the cropping. Framed tightly to fill out the whole of the painting, it adds a claustrophobic quality to the work, intensifying the uncanny atmosphere. This echoes one of the most under-discussed ways that algorithms and smartphones treat images: automatic cropping – for example, in previews in image-editing software or on social media apps – which selects the most relevant areas of an image, i.e. a face, according to what in technological terms is called “visual saliency.”

This function has seen a development akin to facial recognition software, in the sense that images are routinely mapped for key points, analysed according to topographical data, then cropped according to conspicuity, so that they will be recognisable even in a very small size in an overview. This process obliterates any backdrop, any context, or any story for that matter; it is a form of reductio ad absurdum transforming the original image into its own shorthand, nearly a caricature of itself. It can be regarded as a form of brutalisation, making it hard to read the image again after experiencing this extreme abbreviation. Does the pronounced cropping in Wood’s paintings follow or preempt this logic? Is it a form of escalating visual rhetorics?

It’s not a formal innovation, but it changes the story – or, at least, the way we can look at the story. Because maybe Issy Wood’s mythology is too perfect. It leaves out a spectacular sale at an auction three years ago which catapulted the young artist, then barely 30, into superstardom. It anchored her work on the market and established her as one of the most sought after artists of her generation. So, who’s being objectified now? The artist seems aware of this, carefully guarding her own image; she avoids being photographed and refuses to sell her self-portraits. This tactic could be regarded as cleverly nurturing myth and market alike, but is also emblematic of a very contemporary and ever-increasing personal self-objectification cemented by technology and the constantly evolving social conventions around its use.

Circling back to Mark Leckey, it’s interesting to note that his work started out being read in a similar way, as a portrait of a generation. Today this still holds, although some of the early work seems to be reporting from a different – and, today, nearly incomprehensible – society and time. Whatever the future brings for painter Issy Wood, I’m certain it will be interesting to see the invisible hand of the market and the very visible hand of the artist battle it out.