Når Lofoten International Art Festival (LIAF) åpner i Kabelvåg og Svolvær i dag, er det med en rekke poster på programmet. Noe av det festivalen kan by sine besøkende under åpningen, er en suppe kokt på magiske steiner fra den californiske kysten. Mannen bak det noe kuriøse gastronomiske innslaget, er den brooklynbaserte kunstneren David Horvitz (f. 1982). Horvitz, som er utdannet på UC Riverside og Bard College, har de siste årene vakt furore med arbeider som spinner videre på de mer poetiske og humoristiske sidene av den historiske konseptkunsten. Mange av arbeidene baserer seg på systemer for spredning av objekter og informasjon, alt fra det globale postsystemet, til mer moderne plattformer som Youtube og Wikipedia. Mest kjent er antagelig Public Access – et prosjekt som begynte som en reise langs den nord-amerikanske stillehavskysten. Kunstneren lot seg avbilde på over femti strender som i følge amerikansk lov skal være offentlig tilgjengelige. Snapshotene ble så lagt inn i Wikipedia-artikler som omhandlet den enkelte stranden. At Horvitz dukket opp på det ene «offisielle» strandbildet etter det andre, vekket mistanke hos selvoppnevnte Wikipedia-redaktører, som enten fjernet bildene eller klippet ut kunstnerens kontur. Horvitz selv har uttalt at han var mest interessert i sirkulasjonseffekten, og spillet mellom to offentlighetssoner som i prinsippet er åpne.

Wikipedias ambivalente posisjon som kollektivt skapt sannhetskilde blir tydelig i nettleksikonets oppslag om Horvitz’ selv. Her får man vite at kunstneren for noen år siden gjenoppdaget en tapt film av den nederlandske konsept- og performancekunstneren Bas Jan Ader som forsvant til sjøs i 1975, i et forsøk på å krysse Atlanterhavet i en 13-fots seilbåt. Filmen skal ha blitt av funnet på University of California Irvine, der Ader underviste tidlig på 70-tallet. Da Horvitz senere la ut verket, som han døpte Rarely Seen Bas Jan Ader Film, på Youtube på vegne av Patrick Painter Gallery fikk det konsekvenser. Galleriet som forvalter Aders bo, protesterte og videoen ble slettet. Filmen, som nå er tilbake på Youtube med tittelen Newly found Bas Jan Ader Film, er et noen sekunder langt kornete sort-hvitt klipp og viser i et glimt en mann som sykler ut i havet. Verket henspiller både på Aders berømte Fall II der han på sykkel triller ut i en av Amsterdams kanaler, og hans endelikt på havet. Men det handler like mye om eierskap, varestatus og ideen om kunstverkets originalitet.

Horvitz’ spill på kunstens varestatus er preget av ambivalent ironi. Via sine hjemmesider har han tilbudt videoer og bilder som kan lastes ned eller printes ut gratis. Samtidig oppviser han et forretningstalent på høyde med Seth Siegelaub. For øyeblikket er hjemmesiden dominert av et foto av et blomstrende kirsebærtre, ledsaget av følgende tilbud: «For $1 USD I will think about you for one minute. I will email you the time I start thinking, and the time I stop. Make sure your paypal email is up to date.» Tidligere har kunstneren solgt sin atelierleie som kunst, og han er for tiden på utkikk etter en samler som er villig til å kjøpe hans studielån.

Horvitz’ bidrag til LIAF synes å ha et mindre pekuniært preg. I tillegg til steinsuppe, finner vi blant annet installasjonen Lenge leve havet som nå er montert i Smedvika. Kunstkritikk slo av en prat med kunstneren per mail. Horvitz foretrekker å besvare enkelte spørsmål med bilder fremfor ord. Samtalen er gjengitt på kunstnerens morsmål.

How are the preparations for your upcoming show going?

Things are almost done. Bassam El Baroni is great to work with. Chef Arne has left, so all the time I spent eating his fresh bread is now spent instaling. I have work in two rooms in an old house in Kabelvåg. And some other works are scattered around the house walls. There is the work with a flag out on a boat. And there is a soup on Friday made from a stone from the Shawangunk Mountain ridge that I carried in my pocket from New York. We are still looking for a wooden spoon to stir the soup. If you have a wooden spoon, can you bring it on Friday? I want one made from a rogn tree (rowan tree). They are everywhere here.

What do you consider the most important aspect of this particular work?

The wind. The flag needs wind to fly. The wind is very important.

When, how and why did you become an artist?

How do you see your role as an artist today?

Here is a little story: Ryokan was a Zen monk who lived a simple life in a small hut at the bottom of a mountain. One night a thief came to the hut where he found there was nothing to steal. Ryokan was awakened and approached the thief. “You must have travelled far to get here,” he said, “and you shouldn’t leave without having something. Please take my only possessions – these clothes – this is my gift to you.” The thief was confused but took the clothes and quickly went off. Later that night Ryokan sat naked, looking at the moon. “Poor friend,” he thought, “I wish I could have given him this beautiful moon.”

How would you describe your working method?

Sometimes I will develop a project, and it will solidify into one thing. Sometimes it will dissolve into many projects, or into nothing. Sometimes it can act like a mushroom’s mycelium, the underground networked body that can stretch out for miles branching off into different directions, where there is no center, just continuous expansion.

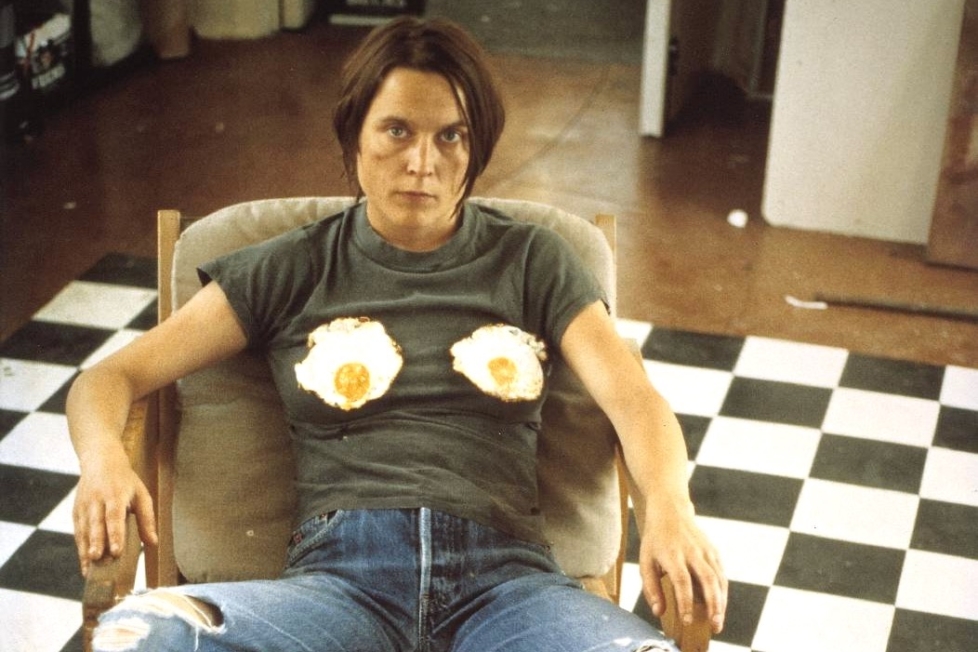

An example of my working process is seen in a room that displays an image of me looking depressed. This image is playing off of cliches found in stock photographs that represent depression. The image was posted to Wikipedia’s Mood Disorder article. Since Wikipedia hosts copyright free material, the image of me looking sad began to circulate as a free stock image for articles in need of an image that depicted depression. It was digested by the internet’s continuous production of content. The room displays about 40 or so examples of various websites in different languages that have used the image. But there was no way to predict this would happen. And there was no way to force it. I just had to wait and see. So I’m always doing things that may potentially grow into something. Or not.

Today, on the way to Henningsvær to get some bole, we stopped at the beach and I made this photograph, which is now here:

Can you mention current art or projects/practices that inspire you?

This past week all my inspiration has come from the cooking of our in house chef Arne Skaug Olsen. The borscht was unbelievable. The halibut was perfect. The chocolate mousse made with avocado with the cloudberries and the almonds… Unbelievable. Hazelnut cake with a brownie on top. Texan chili.

What role does theory have in your work? What theorists have inspired you lately?

Currently, there seems to be a need to define the term «contemporary art». What is it, anyway?

The term contemporary means to be “with time” – or to be “with the times.” But everyone I know never seems to have time. As if it has become a scarcity. (I am, I should say, writing from the perspective of living in New York City…). There are deadlines, things are late, there is always something that demands our attention to be occupied. One hundred new email announcements for exhibitions by artists and galleries I’ve never heard of (how did I get on this list?). Some new things posted about an hour ago, or a few minutes ago, or one second ago. It’s like a race, but there isn’t really a finish line. What is the opposite of “con” in Latin? How can we say to be without time? Sinetemporary? That sounds weird. What about distemporary? Or atemporary?

How can visual artists make a living and still maintain a critical attitude towards the commercial art market and governmental funding bodies?

Again, I am writing from the perspective of living in New York. We don’t have a lot of funding. And not everyone is selling their work. Whether it’s because they are against selling it, or that no one is buying it, they still have to figure things out. Most people I know don’t make their living from sales. Some have a day job. Some have two-day jobs. Some balance out their expenses by shoplifting all of their food from grocery stores. Some live in houses where someone works one day a week at a farmstand, and someone else works part time at a bakery, and no one in the house spends money on food. A friend of mine sells poems on streetcorners in Oakland to pay his rent, and he’s been doing this for years. Another friend sells his own small production wines on the side of his art practice. I used to offer a monthly edition subscription that subsidized the rent of my studio. It was a new artwork each month that was an edition of ten sold at 10% of my studio rent. So they were pretty cheap. Almost all of them are sold out now, which is crazy to think about, because it means none of my studio rent came out of my pocket. It was never a question of the contradiction of selling/maintaining a critical position against commercialism because you weren’t selling anything (except $30 editions). The question was how do you make time to maintain your art practice. I don’t think I answered the question.

What would you change in the world of art?

Less deadlines. Less Facebook event announcements. More openings in the early morning.

Leserinnlegg