Ever since I found out that a retrospective of Lutz Bacher would open at the Astrup Fearnely Museum in Oslo this autumn, I’ve been as sceptical as I’ve been magnetically drawn to Tjuvholmen, that small peninsula jutting out into the fjord from the Norwegian capital. Because, can you even do that? How do you stage a retrospective of this American artist, born in 1943 and deceased in 2019, who was such a deft exhibition-maker herself, and would, no doubt, have found an ingenious approach to the challenge had she still been alive.

Questions kept bouncing around in my head as I strolled along the pier in the dazzling Norwegian morning sun, overtaken by one rosy-cheeked jogger after another. There were also plenty of men with slicked-back hair and thin puffer vests, the kind we’ve come to associate with tarnished tech billionaires, their camouflage familiar from drama series like Succession.

Back in the old days – long before Tjuvholmen became a swanky neighbourhood with eye-watering property prices and fjord views – this was a hangout for the city’s fringe dwellers, including thieves, hence the name “Thief Islet.” And although Bacher wasn’t exactly the kind of artist for whom such site-specific quirks really mattered, she would probably have thought it funny. Not least because she was kind of a thief herself.

Almost all of Bacher’s works are based on things she found at scrap yards, images or snippets of text cut from magazines and books, jokes or phrases sampled from all sorts of sources. Of course, plenty of artists work that way, but Bacher did it with a fascinating lack of plot, making the ground beneath the works shift uneasily. That’s one reason why mounting an exhibition of her art demands a special kind of investment. Not only in monetary terms, even though Astrup Fearnley’s collection has, in fact, been augmented with five major Bacher works since Solveig Øvstebø took over as director in 2020.

In her speech at the press preview, Øvstebø – who curated the show together with Helena Kritis and Dirk Snauwaert from Wiels Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels – freely admitted that the artist herself would hardly have been enthusiastic about the idea of a retrospective. Hence, Burning the Days is a posthumous “survey” filling all three floors of the venue with works from 1975 to 2019, covering almost all of Bacher’s active years. Out of respect for the openness and ambiguity of her oeuvre, the exhibition is more of a loosely organised spread than a cohesive narrative, presenting small constellations of works from different years. Much in the same spirit, the exhibition title is borrowed from a book Bacher never finished.

So how does such an exhibition begin? Not particularly dramatically, in fact: just three works placed in a relatively empty gallery. On the floor, we find Snow White (2009): two metal film canisters which, according to their labels, come from a California studio and once contained the animation classic Snow White (1937). On the back wall hangs Smoke (1976), a somewhat unassuming strip of black-and-white photographic self-portraits showing the artist standing, sitting, smoking or drinking a glass of milk. Leaning side by side against the wall is The Road (2007), a series based on found CCTV footage from the same bend in a winding road, which Bacher has enlarged into eleven large-format photographs. The work has a filmic suggestiveness much in the Lynchian vein, not least due to its repetition of the same curve at different moments in time – as demonstrated by the red digital timestamp, which the enlargement turns into a blurred, fierily glowing border across the top of each image.

It’s hardly a fanfare of an opening, feeling more in medias res. Yet this is what makes it Bacherian in spirit: a gentle mint pastille that tunes in the viewer’s frequency to what is to come. You need to open your eyes, ears, and the stretch of brain cortex in between. Otherwise, you’ll miss most of what’s here.

Or that’s how Bacher is normally conceived. Faced with this many Bacher works, I find myself wondering whether the widespread notion that she’s difficult to understand may have increased alongside a professionalisation of the art world, where so much contemporary art is formatted in the same manner and served up complete with prefab wall labels that save the institutions the effort of thinking – and audiences the effort of looking. Apart from a short wall text in the first gallery, Burning the Days offers no interpretation at all. There’s a handout you can grab, but otherwise you are left with just the works and their titles. I suspect it’s a radical gesture for a museum like this to mount such an extensive exhibition while sidestepping the current reelification of art and mediation. All the same: bravo.

And, of course, Bacher also became “mysterious” because she wanted to be, for example by operating under a pseudonym: a masculine, Germanic-sounding name constructed from her real surname, Lutz, plus “Bacher,” a name differing only by a single letter from that of her husband, Donald C. Backer, an astrophysicist who, amongst other things, studied black holes. Irrelevant on one level, but on another, this nonchalant approach effectively leaves intriguing gaps in the artist’s biography.

It was never a secret that Bacher was from the US, a woman, and married to a man. But the pseudonym broadens the spectrum of identity, including that of the artist as a figure. It also challenges ingrained ideas about the singular author from whom everything supposedly originates. So too does her use of readymades, which continually amputates the very concept in itself.

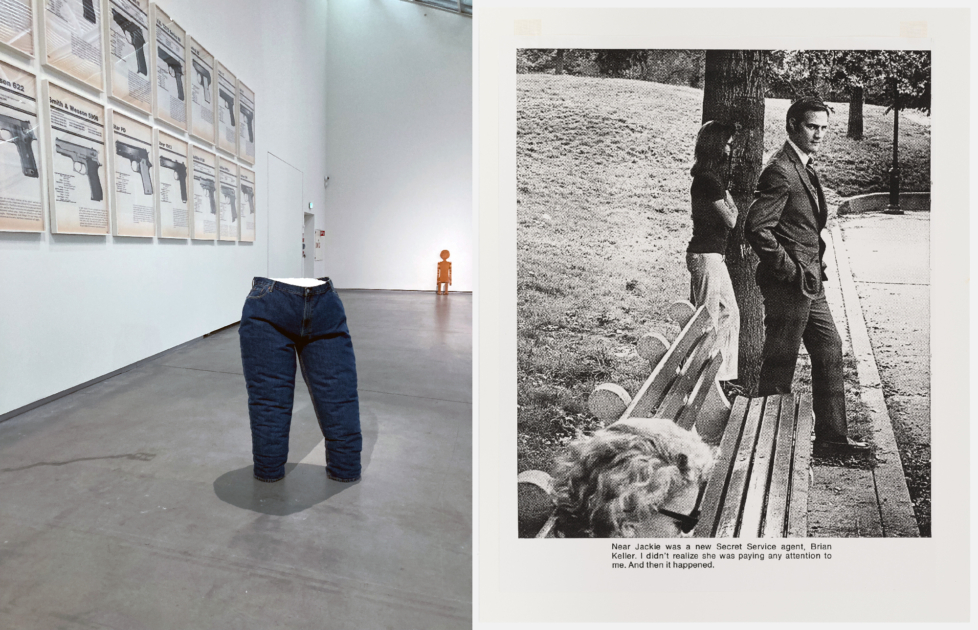

What, for example, are we to make of a pair of size XXXL Levi’s 560 Comfort Big and Tall jeans stuffed to the brim with polystyrene beads so that they can stand upright on their own? Other than laugh, that is. “Sits at waist,” reads the price tag still attached to the waistband, which is, in fact, also true of the appropriated jeans. The stuffing stops neatly at the waist, so the sculpture’s top forms a flat cut revealing its innards: a moonscape of white pellets held in place by the denim container. Fascinatingly simple and fascinatingly stupid; it’s almost a mute statement whose meaning seeps out through other channels. In her essay for the catalogue (forthcoming in 2026), philosopher Juliane Rebentisch notes that Bacher was fond of a term coined by the legendary New York gallerist Colin de Land: “cornceptualism.” The stuffed jeans seem a perfect illustration of that idea.

While it’s been a long time since I’ve wandered through an exhibition giggling this much to myself, the strength of Bacher’s oeuvre very obviously resides in its multiplicity of expression, tone, mood, and mental leaps.

The pink room, for example, is completely devoid of visual jokes. It is darkened, lit only by a single vertical fluorescent tube in the corner. On the walls hang The Pink Body (2017), a series of indefinable foam objects that look like they might once have served as seating, perhaps as inner padding from the seats of an amusement park rollercoaster. The light tube, Pink out of a Corner (to Jasper Johns) 1963 (1991), is a subtle riff on a work by Dan Flavin. In Bacher’s version, the tube touches the ceiling instead of the floor and also exposes its wiring, thereby supposedly accentuating a queer subtext in Flavin’s work. In all its stripped-down simplicity (foam pads and a fluorescent tube), the room still hums with something else, something raw, ragged, and tender, as if a different law of gravity applies here.

Other constellations of works are emotionally gripping in a different and almost intimate way, such as the room containing the black-and-white photograph of Bacher’s husband’s hands, Untitled (Mudra) (1975) as well as the utterly brilliant Yamaha (2010), made just after his death, an electric organ topped with oversized organ pipes that intermittently emit plaintive, trumpet-like sounds like elephants in mourning or a requiem that never quite gets past the opening notes.

In the adjoining gallery, visitors must navigate their way through Stress Balls (2012), hundreds of black stress balls scattered across the floor. On the walls, black-and-white images cut from an astronomy textbook depict galaxies, comets, and other cosmic phenomena. Overall, the room perfectly illustrates the murky intersection – in which Bacher so excels – between humour, art-world conventionalism, and the great mysteries of the universe. The stress balls wink knowingly at a certain kind of dumb ‘lots of the same thing’ art, but also conjure associations with black holes. After all, a foam ball is just as valid an image of that impossible cosmic phenomenon as anything else; no one can grasp it anyway. Moreover, the gesture of handling stress by clenching your fist around a squishy ball is also just an irresistible image of the evolutionary stage our species has reached.

Good art often carries a touch of nonchalance: works seem to be casually dashed off by the artist in an effortless manner you just can’t fake. Bacher was that kind of artist. Often, the effect is created by her juggling something obvious and obscure all at once. Take, for example, the five-minute video Girl in a Blue Dress (2002), in which Bacher’s camera follows a girl, probably in the early stage of adolescence, wandering around the Musée Picasso in Paris. The camera rarely rises above her neck; we seldom see her face, only her pale blue summer dress and bare legs in matching shoes as she moves past the master’s paintings and other visitors. The footage is very obviously handheld, filming the floors, elbows, and rucksacks – perhaps it was filmed without consent? A strange mix of amateur footage, surveillance, and semi-transgression, though nothing really happens.

It is quite surprising that the first large-scale presentation of Bacher’s work since her death is set in Oslo. New York or Cologne would have been more obvious choices. This holds true even though the exhibition was developed in collaboration with Wiels in Brussels where it might, at first glance, fit more naturally within that city’s idiosyncratic mix of Germanic and Romance traditions, and, not least, with its special affinity for the inherent conceptual magic – and humour – in things.

But it’s exciting to see it happen in Oslo, a city that is truly flexing its muscles these days with new prestigious domiciles for the Munch Museum and the National Museum of Norway. To this we may add institutions acquiring large-scale international works and launching ambitious international commissions in steady succession. Oslo has become the kind of art destination no one would have dared predict a decade ago. Yet I cannot remember the last time a contemporary art exhibition actually drew me to the city.

Part of the issue here is that Bacher is not the kind of artist who can simply be ‘imported’ like so much other so-called international contemporary art, drifting from one institution to another in a perpetual lazy flux, like any other global brand. In that sense, this exhibition marks a new departure, and not only for the Norwegian scene. If Scandinavian museums with this level of resources start making exhibitions like this, who knows where it might lead? I’ll believe it when I see it. But Burning the Days was a very pleasant surprise.

Rather than chasing the kind of exhibition that Bacher herself might have made, the curators have clearly aimed for an alternating mixture between moods, caprices, and frequencies, between uncertain territories and assertive punches. They have done this so successfully that, as I passed the puffer-vest men again on my way to the airport train, I found myself thinking of Bacher’s oeuvre as a kind of defence — in the best, most plotless sense — of visual art and the freedom of thought, with all that this entails in terms of jokes, cosmic consciousness, and the collapse of meaning.

Translated from Danish.