I 1994 blev jeg installeret en lejlighed i Zürich sammen med to kritiske og diskussionslystne unge tyske kunstnere fra Berlin, Judith Hopf og Florian Zeyfang. Hopf og jeg skulle være med på udstillingen Game Girl i kunsthallen Shedhalle ved Zürich See. Der blev spist Müsli og Appenzeller-ost og drukket Feldschlösschen og det blev for mig et vigtigt møde med den kritiske impuls fra Berlin, som kendetegnede byen før den blev en international kunstmetropol. Judith Hopf har været en del af den selvorganiserede scene i Berlin siden starten af 1990’erne og har blandt andet behandlet temaer som arbejde og magtstrukturer i det offentlige og private rum, som regel med video eller skulptur som medium.

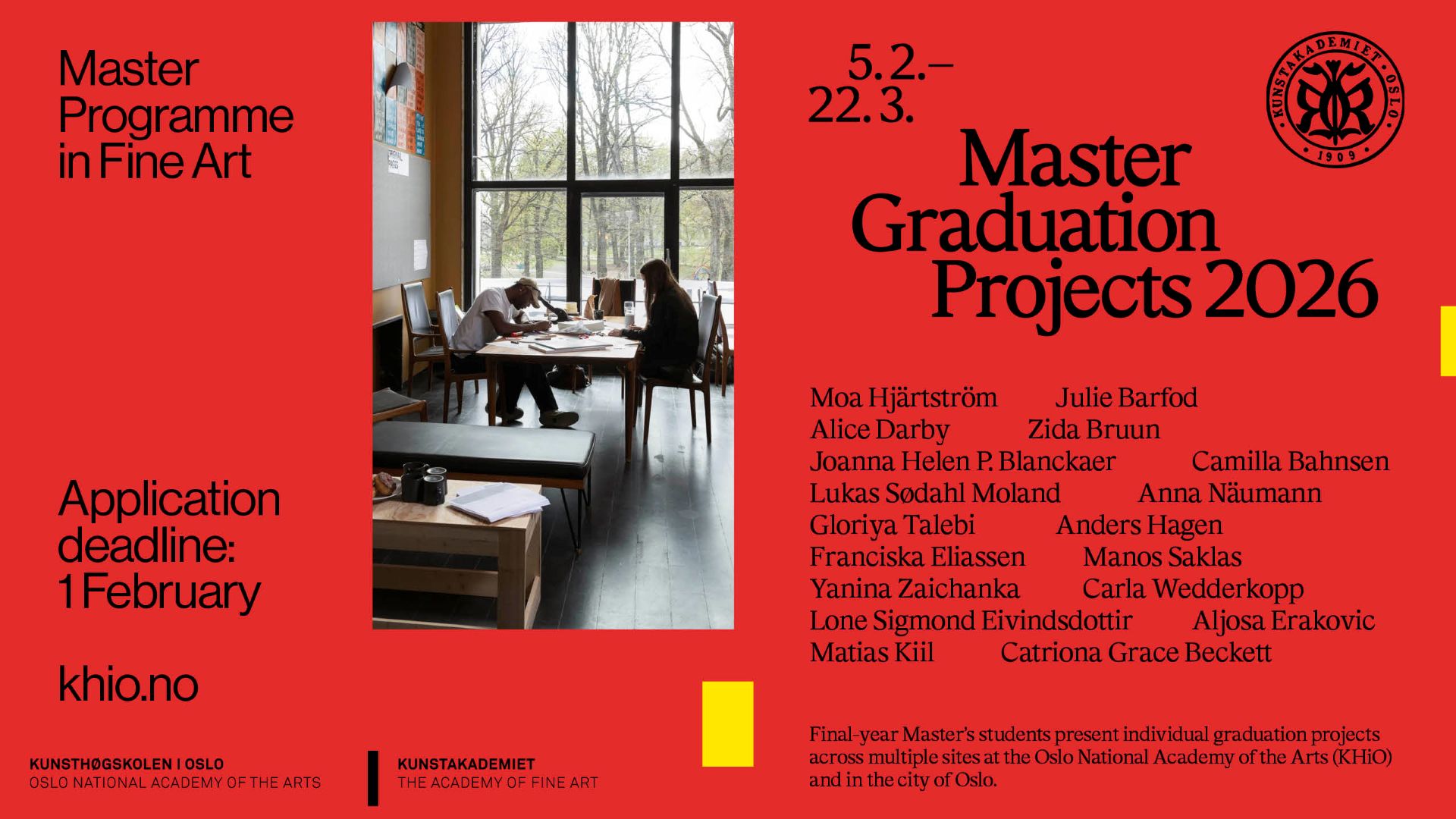

I aften åbner Hopf en udstilling på Statens Museum for Kunst i København med en flyvende biograf, kæmpepærer i mursten og laptop-skulpturer. Udstillingen i København er en ny udgave af Hopfs nylige soloudstilling Stepping Stairs i Berlin på Kunstwerke, som den også er organiseret i samarbejde med. Hopf var professor ved Det Fynske Kunstakademi fra 2006-2008 og siden 2008 har hun undervist på Städelschule i Frankurt am Main og det er tydeligt at Judith Hopfs kritiske diskurs stadig virker – nu også på en yngre generation af kunstnere.

Samtalen foregik på engelsk.

Judith, I have been waiting for more than 20 years for you to have a solo show here in Copenhagen. What are you showing us?

I’m showing a group of sculptures that the museum was co-producing together with Kunstwerke in Berlin, where I developed a bit larger show with also older works. Here we only see works from this year. I got quite materialistic in the last five years, and I developed these still figures with maybe a nice handshake to the modernistic sculptures which are called Laptop Men, and it is a bit of a study of gestures of the laptop or iPad we have on our bodies while we are hanging around in transit zones such as airports or other places where we have to wait. We try to overcome time with the laptop. I think we get a special body language in public, where the laptop is included, almost as a part of the body. It’s an attempt not to be too talkative or moralistic about a theme, an abstract attempt to deal with the animation of abstract forms, to feed it back to the body where electronic tools are already included or thought in.

Then I made another work where I deal with architectural leftovers. These are brick stone sculptures. Here in Copenhagen, I show Pears, which are computer cut. In Berlin, I also showed some hand cuts. It’s done after a drawing and now it’s quite rough. It can be seen as a greeting to Per Kirkeby as Marianne Torp, the curator here, is very amused by. They are very heavy and quite hard to handle and not very flexible or conceptual, they are physical. Like the architecture of the museum here, they are reproducing this Nordic culture of building in brick stone.

I also show a new film, a 2-minute long video, of a social housing project in Berlin, which was developed after the squatter movement. Here they tried to build houses for multiple uses not only for normative heterosexual need of possessions, but also for artists and others types of singles and new type of families. It’s a very comic house.

Is that the John Hejduk house, the Kreuzberg Tower and Wings?

Yes, it was originally built in 1998 for the DAAD, the residency program for artists, literature people and musicians, and then it was developed further as a social housing project, and now later it has been privatised. I love this house. But it’s a bit of a challenge this building, often criticised for its unreasonable form. It’s not nice at first sight but when it’s raining then it cries when the water drips down from its sunshades. It’s really special.

Did that house inspire your own housing cooperative – the one you built with your partner Florian Zeyfang and friends of yours in Berlin?

It’s true we also made a housing experiment close to it, and if I look out of my own window I look onto this skyline of the Hejduk house. But yes, we tried to make and experiment of how we could live together in Kreuzberg.

The title of your exhibition in Copenhagen is ”Out”, but you are “in”?

I don’t know, maybe I am in the house, but I try to be out in political ways just as the gay people are out. I really love Copenhagen, but it’s so in, in fashion, so I thought I had to shout ”Out”. The film is also called ”Out”.

But you are very much in vogue as an artist?

It doesn’t feel like that, but the Kunstwerke show had very good press. There was a good mood related to the show, and some people felt inspired and that’s a big honour.

In the Kunstwerke exhibition you included works by Anette Wehrmann, a conceptual artist who also came out of the self-organised scene in Berlin and deals with issues such as money, religion and language. Why did you use Anette’s works in the exhibition?

She is dead, did you know? I miss her so much … I started the idea of working with bricks because I had a mental call from Anette, she worked in the early nineties in a different way with brick stone, but she also did these performances where she tried to kick stone balls, footballs made out of stones, but she was much better than I am because she did it all wrong. Sometimes if I get too pretentious, she reminds me that she took her time to develop things, and she was also not too much triggered by the idea of representative idleness. At the same time, she remained hyper sensitive. That’s what I admire as well as her spontaneity.

I also want to support that the inspiration I get from her is included in the process. You’re also an artist, and I guess you know that you get inspiration not only from yourself but also from all the other people around you. I think it’s interesting to point that out and also name it and say: This is inspiration, and it should be established in this circus we are running in.

Beside Anette’s work, what turns you on now?

I am quite ignorant at the moment. We both come from the nineties, from the discursive era, where a lot of thoughts were included in the art and I’m still very much in my heart trained by that. For a certain moment I thought that aesthetics had this power to change real politics, and it was quite frustrating to acknowledge that that is not true. I learned, I cannot stop the Iraq war. The political work has to be done next to the aesthetics and not with it. That is why I changed my language into something more indirect, which led me to a quite traditional hand crafty position. But I’m still obsessed with society, and the fantastic forms of getting together.

But then, is the role as an artist now less political?

From my personal observation I learned that we have less control over the democratic systems, over economy for example. And if it’s like that, I have to learn how I can satisfy my everyday doings without getting sad and that’s why I am doing a lot processes where a can see a clear beginning and end. So I have developed from being quite a conceptual artist to a more hands-on artist. That was maybe why we built our own house. Instead of being on the moralistic-critical side, always just talking and thinking about the right things, the constructive moment became more important.

Can you explain the relationship between the use of mundane objects and materials such as bricks and steel and the marginalised themes that often occur in your art?

The thing I have learned is that I’m not a very technical person. Maybe you could refer the bricolage method to the ideas of Claude Levi Strauss. Working with things that surround you, whether it’s stones from architecture or everyday culture, means that you are not a constructivist, but use a different way of thinking. Levi Strauss said that the society creates hierarchical thinking systems. Therefore, maybe it’s quite interesting to be part of and to seek to change things you cannot change. The bricolage idea is more on the wild and uncooked side, because you not only believe in the youth or the new, but also include things that are already done.

When I look back at your oeuvre, you strike me as a very free and daring artist, even if you lived through a lot of changes; coming from a left-wing position on the old Berlin art scene, a lot of teaching and in the last ten years significant commercial recognition. How do you operate within all this and stay “free”?

I still assign to the left wing. I don’t know how much you’re able to decide within your own life. At a certain point, coming from the nineties to the two thousands, I was constantly saying “no” to things – no, I don’t want to do this or that. Then I recognised I didn’t know what was am saying no to. In a way, I was worrying about selling out before even selling something. Then I decided on another extreme and started to say yes to everything.

It can’t be that all we left-wing artists are always on the perfect moral right side while existing in the most conflict-filled zone with economies which include the worst banks or the hottest weapon dealers. I just thought that for me, the outside position isn’t possible, it’s not a better position to say no. So I tried to keep on focusing on the subject that I am working on. I wanted to get richer, not money wise, but aesthetically. But I needed support and I had to stop whining about the contradictions within the market. I try to take it a bit easy, but I don’t feel peaceful with it.